Alfred Traum

Three Essays

Alfred Traum who had to leave Vienna at the age of ten on a Kindertransport, describes in his essays some memories of his childhood - the last Sabbath meal before leaving, his interest in the neighbour's gasmask, the farewell and the return as a tank commander with the Royal Scots Greys.

The Kiddush Cup

It was always the same. Ushering in the Sabbath, my father held the silver Kiddush [1] cup in the flat palm of his hand with his thumb resting against the brim of the cup, his head held high, eyes half closed as he recited the blessing over the wine. We all took a sip from the Kiddush cup.

That and all the other festive traditional activities were carried out in their proper order. Any bystander would have thought this was just an ordinary Friday night in a Jewish home. So it would have seemed. But I am sure that both our parents' hearts were breaking. My sister and I were leaving for England on the following Tuesday. This would be our last Sabbath dinner together. Although we thought that we would soon be reunited, our parents knew the difficulties that lay ahead. And indeed, it was the last Sabbath meal we shared.

Preparing for the Sabbath actually began Thursdays, with my mother laying out large round thinly rolled dough that would later be used to make noodles for soup. She busied herself in the kitchen all evening making mouth-watering selections of cakes that would last through the entire week. We never bought any ready-made cakes. Everything was homemade. That particular week she would need more since many friends and relatives would drop in, say their goodbyes and wish us well on our journey. Friday morning I would watch, as I had watched so many times in the past, as she braided the dough to make the challot [2], then basted them with egg yolks and lightly sprinkled poppy seeds on them before placing them in the oven. The aromas from the baking and the food preparation permeated throughout the home. A rare and wonderful smell that, even now, can whisk me back in time when on a rare occasion, something comes close to it. This was the routine in our home, and very likely in many other Jewish homes in Vienna.

My father was crippled as a result of his service in the Austrian Army in the First World War. I never really knew what his exact diagnoses was, but he could only get around with the aid of two walking canes. However, when he was seated, there was nothing that he could not do. He had gifted hands that could turn to so many things. An artistic flair that enabled him to create beautiful drawings and teach how to use proportions and take perspectives into account. Although he never trained to be a tailor, he handled the sewing machine like a professional, making all kinds of clothes for us, even a new suit for me. He could turn his hands to all sorts of activities, resoling shoes, repairing electrical apparatus that had ceased to function, and he even tinkered with the radio when it went on the blink and somehow managed to get it functioning again. He was also an amateur photographer, doing his own developing and printing. We never went to a photography studio; as a result, I only have small snap shots which he had made himself. As a little boy I used to watch his every move picking up many cues which I would store away for use at some future day. He never complained about his handicap. I learned so much from him, but above all, he taught me how to live with adversary and make the most of it.

Years later as I developed my own hobbies, amongst them rebuilding automobile engines or building an addition to our home, friends used to ask, "Where did you learn to do that?" I would simply shrug my shoulders, but somewhere in the back of my mind was my father telling me, "Go ahead, you can do it." Perhaps it sounds far fetched, but he taught me so much without leaving his chair.

On the Tuesday of our departure for England, we all went downstairs to the back yard where my father set up the tripod and camera, placed a black cloth over his head and focused the camera on us assembled for him to take a picture. He selected delayed shutter feature and joined us in the photograph.

Our mother was taking us to the Westbahnhof, the railroad station for trains heading west. As we were about to leave, my father said to me, "Go forward and don't look back." I was never quite sure of what he meant by that statement, but I believe it to have been more philosophical in nature than in the literal manner a small child would take it. However, as the three of us proceeded along the sidewalk and still a short distance from our home, I did stop and turned around to look back, and just as I expected my father was at the bay window with tears in his eyes, forcing a smile, watching us walk out of his life.

When the photograph had been developed, a copy was sent to us in England; it captured all of our feelings. It is the saddest picture I have ever seen, nevertheless, it is a treasured memento of that day. On one of the negatives my father had written (in German) "Der Abschied", The farewell.

At the train station the platform was crowded with parents coming to see their children off on the Kindertransport and to a new life in England and hoping they would not forget their old lives and those who loved them. It was a special train just for our group, probably a couple of hundred kids from very little ones scarcely more than toddlers up to the age of seventeen. [3]

We stood at an open window holding hands with our mother. She too was fighting back tears, trying to tell us that it would be just for a short while. I don't think she believed her own words, but what else could she say. We were bravely looking at each other not knowing what to say when suddenly my class teacher, professor Schwartzbard, appeared in front of us. He knew I was leaving on the Kindertransport on that day and apparently had managed to have his young son accepted too. He was holding his five-year-old son like a piece of luggage under his arm and passed him through the open window and asked if he could sit with us and that I might keep an eye out for him until we reach London. In London someone would come to pick him up. Naturally I agreed and immediately I felt grown up, with a new found responsibility dropped in my lap. A whistle blew and we kissed and hugged through the open window, reluctant to let go as the train began to pull away. My mother tried running along with the train holding on to our hands, but not for long. Soon her lonely figure diminished as the train snaked its way out of the station.

All our worldly belongings were packed into two large rucksacks, stuffed to the brim with clothing plus lots of sweets and chocolates that friends and relatives had given us. My parents sent along a very nice box of chocolates for the Griggs family who had agreed to take us into their home. We were not permitted to bring along any items of value, such as jewelry or money. I took the chance and hid the wrist watch in my pocket. The present my parents had given me on my tenth birthday. However, small snapshots were not considered of value and we had several family photos. Through the years their value, to me, has increased enormously since they represent the only visual recollection I have of my former life with my parents.

In writing this story, I do not intend to write about our time in England, but instead to focus on just two dates that punctuated my life. The first, a rather sad day, yet marked with hope and promise, the 20th of June 1939 when my sister and I left Vienna for England, and the second date, the 24th of June 1958, a happy event of my wedding to Josiane Aizenberg aboard the Israeli passenger liner S.S. Zion, while the ship was docked in New York harbor. My sister had come from Israel to be with us on our special day. She had a very special gift for me, one that she had been saving for such an occasion.

It was my father's Kiddush cup. The same cup I had seen on so many Friday nights. It came as an utter surprise to me. I had no idea she possessed it.

Apparently, my father took an unprecedented risk and stuffed it in amongst my sister's clothing, without telling her, but knowing she would know what to do with it and when the moment was right to pass it on to me. That moment had come, my wedding. But more importantly, in parting with his Kiddush cup, which he had most likely received on some special occasion, he must have been acutely aware of the severity of their situation and the doubtfulness of their survival. It is my most-prized possession. Every Friday evening, as we usher in the Sabbath, it graces our table. Perhaps I don't hold it in the same manner as my father did, but I recite the same blessing over the wine and gratefully look around at my family and think,

"How fortunate I am to have had such wonderful parents."

The Gas Mask

Herr Tamer lived at the end of the hall. He was a tall gaunt man, a very private man, or so it seemed to me as a nine-year-old. A lonely figure that responded pleasantly to my greeting when our paths crossed. One day he knocked at our door and asked if he could come in to listen to Hitler's speech. He didn't own a radio and knew we had one, even though it was old, still it was better than nothing.

So, Herr Tamer and my parents gathered around the radio when Hitler began his speech. It went on and on for ages. Mostly ranting and raving and frequent interruptions of "Sieg Heil" I couldn't concentrate on what he was saying, but noticed my parents. My mother's eyes were moist and close to tears, my father sat stony faced. Herr Tamer gave no indication or sign of emotion to the "Fuehrer's" utterings. But deep down I knew whatever Hitler was saying was not good for us Jews.

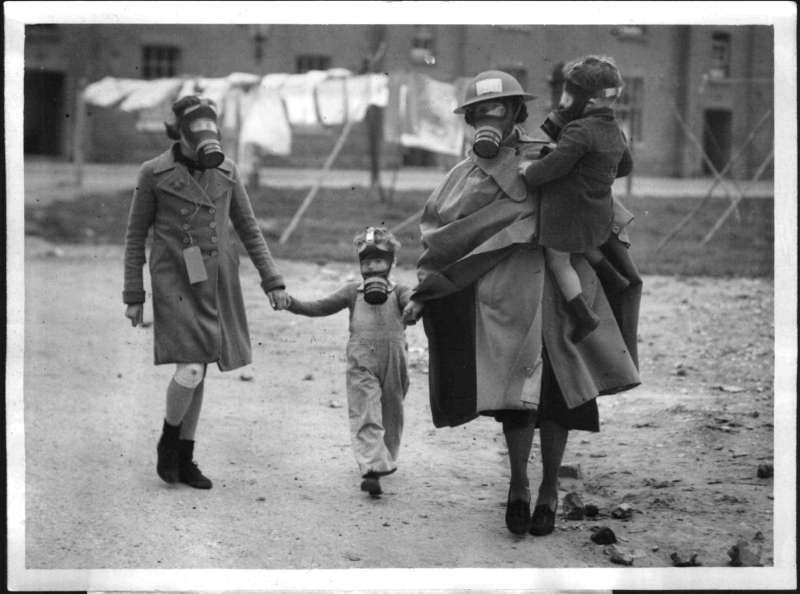

I was more interested in Herr Tamer's gas mask case. He noticed my gaze, removed it from his shoulder, opened the lid and handed it to me for a closer inspection. It was a dark green round metal canister with fluted sides. Herr Tamer had been enlisted in one of the many organizations that sprung up under the Nazi regime. He wore an armband identifying him as a member of the NSKK [4]. As far as I knew that seemed to be the extent of his uniform. I have no idea what the initials stood for, but one thing I did know it rated a gas mask. Many people, by that time, were walking around with gas mask canisters slung over their shoulders.

Of course gas masks were not issued to Jews.

That wasn't the first time that my parents and Herr Tamer had gathered around the radio to listen to similar speeches and always with the same emotional impact. The worsening situation for Jews living under Nazi rule was already very much in evidence. Restrictions, persecutions, fathers abruptly disappearing without warning. In some cases reappearing, after several months, and given literally only days to leave the country. We learned later that they had been incarcerated at Dachau or Buchenwald.

The signs were all there. There was no future for Jews under Nazi rule, the only question remained, where to go? Who will let them in? My parents had received visas for the United States, but it all happened too late for them. In 1942 they were shipped east to Minsk and no word from them or about them after that date. [5]

In June of 1939 my sister and I left on the Kindertransport for England. We were fostered with an English gentile family that lived in London. The following Monday morning, after our arrival in London, I was enrolled in the local school and placed in a class appropriate for my age. I spoke only several words of English, which was just enough to get me into trouble. When one of the boys asked me, "Do you want a fight?", I used the one English word in my lexicon and answered "yes". I wasn't sure what he wanted of me, but was certainly shocked and surprised when he punched me. I quickly learned that I had to improve my language skills.

But when it came to arithmetic and problems were written on the blackboard for us to solve, they seemed pretty straight forward for me. However, the teacher was puzzled that my answers were correct; I finished before anyone else in the class but she couldn't figure out how I got there. Apparently, we learned maths very differently in Vienna and did much of the calculations in our head. The English method seemed very long-winded to me. I thought, at least here was one subject in which I excelled. But she wasn't happy with that. She wanted me to do it the English way and spent a considerable amount of time on the blackboard teaching me the English method. She needed to see how I arrived at the answer.

When it came to composition time the teacher indicated that it would be fine if I wrote my essay in German. It provided me an automatic "A" since she couldn't read it and judged me mainly on quantity and neatness. I knew this wouldn't last for long.

A school staff member interrupted the class and asked for me to be excused and indicated that I should follow her. She took me to a store room and pulled a square carton from the shelve. On opening it up I discovered it was a gas mask. Smilingly I accepted. Like all the other boys I was being issued my own gas mask. She showed me how to put it on and then proceeded to adjust the rubber straps. When she felt confident that all the adjustments had been correctly carried out, and for a final test, she held a piece of paper over the bottom of the mask and indicated for me to take a deep breath. She did this by inflating her own chest and motioned for me to follow suit. As I inhaled the paper held firmly to the mask, there were no leakages. She then wrote my name on the box and with a friendly pat on the back handed the box to me and told me to return to my class. For her, it seemed just the normal and right thing to do. However, to me, that gesture had a much deeper meaning.

During play time, many of the boys were swinging the gas mask cases around and throwing them, playfully, at each other. I held mine proudly into my side. To me, it was an affirmation, that here in England I too mattered. I really mattered.

Keep Off the Grass

The moon glistened on the river Weser as our long column of Centurion tanks made its way back to our barracks at Lüneburg. We were passing through the town of Hamelin. [6] The very same town that gained fame through the stories of the Pied Piper that rid the town of the rat infestation many centuries ago. The street was lined with neat houses and manicured lawns to our right and the river to our left. We rumbled along noisily, the tank tracks clattering on the cobbled street shattering the still of the evening. Here and there lights flickered on as home owners drew back curtains to see what the noise was all about. We were not welcome guests there. It was late summer of 1952 and the conclusion of a month of Rhine Army [7] maneuvers.

My thoughts of the Pied Piper were abruptly interrupted by Dinger, our driver (all persons with the name Bell are nicknamed "Dinger").

"Fred, what's that sign down there on the lawn? What does it say?" Being aware that I knew some German, he was for ever asking me to translate signs for him. I don't think it was his thirst for knowledge but more out of boredom being stuck away in the driver's compartment.

I took a look. The sign read Betreten verboten. "Oh, it just means keep off the grass," I answered.

"Thanks," he laughed.

As I took a further look at the neat oval cast iron sign with its raised letters it triggered a memory long thought dead. Like an odor, a familiar sound or the sight of something stored in your memory bank, it has the power to transport you through time to recapture that moment. That was the effect that sign had on me.

I could feel the frustration and rage rise within me. I was again that nine year old boy in Vienna returning home from school. As usual, I took the shortcut through the park. What used to be fun, coming home with my classmates, had turned into a daily nightmare. These were the same kids with whom I grew up, and with whom I had played all the time. But since the "Anschluss" [8] they had all been enlisted into the various Nazi groups. The poison spread within them. At first they just distanced themselves from me, shunning me, which later turned to name calling, taunting, pushing and shoving. On the particular occasion the sign brought to mind, one of the boys ripped my school satchel off my back and threw it on to the grass. They all laughed as they ran away. As I stepped over the small railing, surrounding the lawn to retrieve my satchel, a policeman suddenly materialized, seemingly out of nowhere. He must have been there all along and witnessed the whole scene, probably enjoying it too. Now it was time for him to have some fun. He caught me by the scruff of my neck, dragged me on to the pathway and gave me a harsh dressing down.

"Don't they teach Jew boys how to read," he said pointing to the sign.

He then took down my name and address. Several days later a letter was received ordering my mother to come to school. She came to our classroom. As was the custom, out of respect for elders, all the students stood up when an adult entered the classroom. The class stood up as my mother entered.

"Sit down at once. You don't need to stand up for her," the teacher barked.

He then went into a lengthy diatribe about the lack of respect Jews seem to have for the beauty of Vienna's parks. My mother and I stood in silence having to listen to one insult after another before being dismissed.

Shortly after that incident, but probably not because of it, I was expelled from that school and transferred to a School for Jews. This is not to be confused with a Jewish School, which is generally a choice to provide a Jewish education. No, this was a school were Jews were herded together so they would not be able to infect Aryan children. The school was much further from my home and I had to take the streetcar for several stops. But, apart from that, it was a far happier place to be, to sit once again among friends. Our teacher, professor Schwartzbard, was an excellent and wonderful teacher. He had taught at the university level but, because he was Jewish, was let go and relegated to teaching fourth graders. Their loss was our gain. We all liked him.

Frequently a bunch of bullies hung around in front of the school when we left to go home. Since I didn't live in a Jewish neighborhood I had to make my way home alone. On more than one occasion I was chased. I never slowed down to find out what would happen, I outran them all. I was fast.

Streetcars traveled in the center of the road and motor traffic had to stop when the streetcar came to a halt. There were little islands for people to stand before boarding the streetcar. On one occasion, when I was waiting for my ride, for some unknown reason, the streetcar's doors closed and left me standing, the driver probably hadn't seen me. As I took a step backward, I was hit by the fender of an oncoming car and knocked to the ground. The next thing I knew, a man standing over me, inquiring, "Are you hurt?"

"No," I answered.

"Where are you going?"

"To school," I answered, somewhat nervously.

"Jump in, I'll take you to your school."

I thanked him and climbed into the passenger seat of the car. It was a brown staff car of the dreaded SA. It had a little Nazi flag attached to the fender. The man driving the car was an officer in the SA. Generally, when a car of this type pulled up in front of a school like ours it spelled trouble. It wouldn't be a social call. But that time was different, you should have seen the look of some of my school friends when I stepped out of the car. It was the talk of the day.

To top it off, I bought an ice cream with my fare money.

But not all days finished off in that satisfying way. One day when I was being chased by a bunch of bullies I quickly turned into a side street and ducked into the first building entrance. These buildings were old and had massive doorways that could accommodate a fully laden horse and cart. Two doors swung inward to the side of the entrance. There was just enough room for me to squeeze behind the door. I had often played hide and seek and used the shelter of these large doors. I could hear the boys, as they came to the corner of the street, talking as they were looking around and wondering to where I had disappeared. I stayed there, what seemed to me an interminably long while. I thought that the beating of my heart would give me away. To me, it sounded like an anvil being pounded at a blacksmith's shop. Outside, the sound of the boys had stopped, they had given up their chase.

I continued to stay there a while longer and then with the relief of being safe I felt the sudden warmth around my shorts and legs. I had wet myself. I was so ashamed, transfixed, I was unable to move. I lingered a while longer then finally made my way home. Not long after that experience, I left with my sister for England on the Kindertransport.

Telve years later, I was back in former Nazi territory. Although I had been too young to have fought in the war, nevertheless, I was there, in Germany, not as a victim but as tank commander with the Royal Scots Greys [9], The British Army of the Rhine occupying forces. The weight and power of the Centurion tank, with all its armament, felt good beneath me. Perhaps there is some justice in the world after all.

"Keep off the Grass" and "The Kiddush Cup" have already been published on the website of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, "The Kiddush Cup" has aditionally been published in the book "Marking Humanity" in 2010.

In addition to these essays here you can read some more details about Alfred Traum's life.

[1] Kiddush (Hebrew: "sanctification"): blessing to sanctify the Sabbath and Jewish holidays.

[2] Challah (pl. challot): special bread eaten on the Sabbath and Jewish holidays.

[3] Between December 1938 and September 1939, around 10,000 Jewish children and young people escaped from the German Reich to Great Britain with so called Kindertransporte.

[4] Nationalsozialistisches Kraftfahrkorps (National Socialist Motor Corps), a paramilitary automobile and drivers' organisation.

[5] Fred Traum's parents were deported to the extermination camp Maly Trostinec near Minsk, Belarus, where they were murdered.

[6] Lüneburg and Hamelin (German: Hameln): cities in Lower Saxony, Germany.

[7] The British Army of the Rhine: name of the British occupying forces in Germany after WWII.

[8] The "Anschluss" refers to the annexation of Austria and its integration into the German Reich on March 13, 1938.

[9] A traditional regiment of the British Army (1707–1971).