Frank Beck

Refugee child

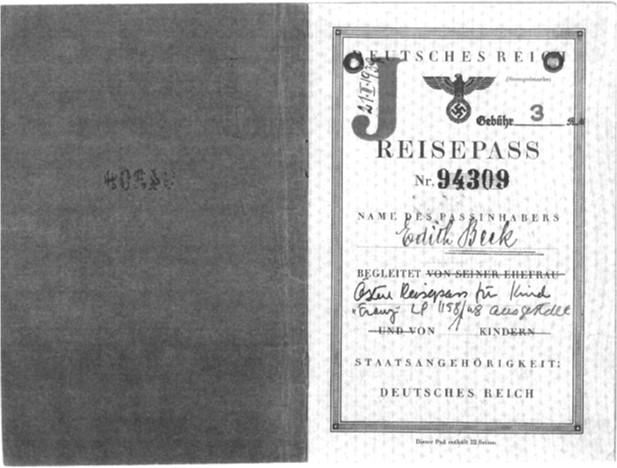

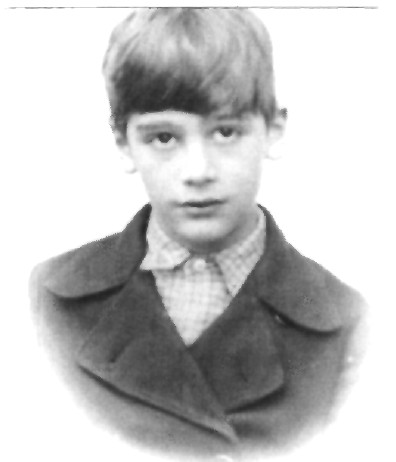

Frank Beck was born on 28 December 1930 as Franz Beck in Vienna. He emigrated with his mother in March 1939 to England. His father was killed in Auschwitz.

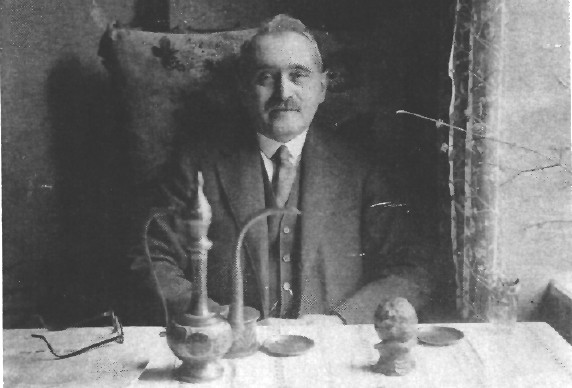

My paternal grandparents, the Becks, were from established Jewish families, resident in Austria for several generations. My grandfather Ferdinand Beck was a successful businessman, and the family ran three shoe shops, two of them in the best part of town. They were no longer religious, but they were very conscious of their Jewishness, and in particular would have disagreed strongly with marrying out of the faith. They had two daughters and a son, who was my father Friedrich.

My maternal grandparents were recent arrivals in Vienna. They came from a small town called Nitra, near Bratislava in Slovakia, and at the turn of the twentieth century established a home in the 2nd District of Vienna and a general store with which to earn a living. They had two daughters, one of whom was my mother Edith. They were observant Jews: they belonged to a small prayer house nearby and kept a kosher house [1].

My parents met in a bar; they had been introduced by friends. They married and found a flat in the 9th District, and in due course had what turned out to be an only child. I was born in Vienna on 28 December 1930. My birth was registered by the Jewish authorities, rather than by the state, as births, deaths and marriages were the responsibility of religious authorities in the Austria of that time. [2]

My mother worked in the family shops of her in-laws. My grandfather Beck had insisted that all family members work in the shops. I was looked after by a young girl, Rosina, who was the daughter of the concierge in our apartment block. I am told Rosina regularly took me to the shop nearby where my mother worked to be breastfed. I saw little of my father. He worked in a different shop and his one day off every week was usually spent watching football while my mother took me to visit her parents. But occasionally we would all go out together for an outing as a family.

At the age of six I was sent to the local school. Then came the “Anschluss” [3], and the beginning of life under the Nazi regime. Just before it happened, my father decided to abandon the family and escape to France. I actually have the document making my mother my official guardian in his absence.

As soon as the Nazi edicts began to take effect my grandfather Beck gave his businesses to a non-Jewish employee and escaped with his family to Cuba, there to await a visa for the United States. My mother’s parents were not so lucky; they lost their home and shop to a predatory Nazi and had to move, penniless, to a small slum flat nearby.

The effect on me was that I had to leave the school I was attending and move to an exclusively Jewish school with Jewish teachers nearby. [4] Rosina was soon to lose her position as my nurse. She was no longer allowed to look after me, but of course my mother had lost her job, so she could take over full-time responsibility. I prospered at the Jewish school before the summer break and beyond it into the new school year, and enjoyed learning.

My father had escaped in time. Had he remained in Vienna he would certainly have been arrested and sent to Dachau [5]. He was now safely in Paris, and would be able to get us all to the safety of America in due course. My mother decided to move in with her parents, so we travelled across Vienna to join them in their flat in the 2nd District. From there she still took me to school every day.

Then came 9 November 1938 [6]. I was at school as usual, when my mother came during an afternoon class to bring me home. We also fetched another Jewish boy whose parents had asked my mother for help. On our walk across the town we saw buildings on fire, and mobs rampaging. Old people were being made to scrub the pavements on their knees and other people were being beaten. My mother tried to protect my eyes by covering them with her hand, but I was able to peep between the fingers. She tried to shield her child from the awful scene, but I saw enough to be a witness to it during the rest of my lifetime.

We deposited the boy we had been looking after and returned hastily to my grandparents’ home. I only once left the house after that. A week or two later my mother took me to the Westbahnhof [7] with a little suitcase and tried to put me on a Kindertransport [8]. She explained to me that it was to send me to safety in England and that she would be coming to join me soon afterwards. She put me into the carriage while still talking to the organisers on the platform. I watched out of the window.

Apparently there was something wrong with the documents. I was taken off the train and my mother brought a very relieved seven-year-old back to the grandparents’ flat. I was to remain indoors for the rest of my stay in Vienna. It was unnecessarily risky for a Jewish child to be outdoors in Vienna at that time.

But grown-ups were outdoors on missions. My mother was looking for alternative ways to escape, using the fact that residence permits were available in England for domestic servants. A young Jewish student came in once a week to teach me English. It was during this time that my mother and my grandfather gave me some Jewish religious education and taught me to pray.

I never went outdoors again. It was too dangerous. For the next few months I slept in a room with my mother and my grandparents. My mother practised cooking. She had always had domestic help, and now she was going to be someone else’s cook-housekeeper.

On 13 March 1939 we left my grandparents’ flat and went to the Westbahnhof, this time apparently equipped with all that documentation that my mother had spent the preceding months acquiring at great trouble and expense.

A cousin of my mother’s, Tante Fritzi, accompanied us. She had obtained employment in the same English household as my mother, and they would be living and working together.

We travelled through an Austria and Germany bedecked by swastika flags to celebrate the anniversary of the “Anschluss”, and arrived at Liverpool Street station [9] after a 24 hour journey. It had been the first time I had been on the sea in a boat. There we were greeted by my uncle and auntie, who took us back to their boarding house in Belgravia [10]. There was a room for my mother, but I was to sleep for a few nights on two tub chairs pushed together.

I was reunited briefly with my cousin Inge when she returned from school. Indeed we all spent the weekend together, before my mother was due to start work in Essex [11]. I was to go and live in a hostel for refugee children in Hampstead [12].

The hostel was in a large house at no. 254 Finchley Road. There were about a dozen boys there, all German and all older than me. I was the only Austrian child. Nonetheless, I settled in quickly, and I don’t remember feeling too miserable. I was soon enrolled in a primary school down the road at Swiss Cottage [13], and grappled with education in a foreign language. Not too difficult, as it happened; I had been quite well prepared.

Then it all broke up for the summer holidays and we had a very pleasant time as a group, going out on organised visits, swimming on Hampstead Heath [14], and so on. From time to time I was fetched at weekends by my uncle and aunt, who were settling in in a flat in nearby Compayne Gardens [15], and once or twice we were joined by my mother, who came down all the way from Essex to visit on her day off. It was on one of these visits that I was told that the family had contrived to get my grandparents out and that they would be coming to England to live in uncle and auntie’s flat. I now had a family again; we just weren’t all living in the same place.

After the summer holiday we returned to school. All the talk was of the possibility of war, and children in London would be evacuated to the country, to shelter them from the risk of bombing in the towns. Our school was to be relocated to Abbots Langley in Hertfordshire [16], and we would be billeted with landladies who would give us our food and look after us.

After a number of attempts I finished up with a delightful childless couple who looked after me for the early years of the war. I had to leave because I won a scholarship, and to take this up it was necessary to relocate to Minehead in Somerset [17], where a recommended grammar school from London had been evacuated. I lived with a number of seaside landladies and in various hostels, visiting my mother in London for the school holidays. My mother had needed to leave the Colchester [18] area because it was a restricted area for foreigners, and had been lucky enough to find a Jewish family to work for in Finchley Road near her parents and her sister in Compayne Gardens. This family also agreed to have me staying with their domestic servant during my school holidays.

During this period it gradually became evident that my father’s move to France had been a mistake. Letters to my mother made it clear that Jews in France were in trouble, especially foreign Jews. He moved to the South, which for a time was unoccupied by the Germans, but eventually he was interned at Les Milles [19], held in the notorious Velodrome at Drancy [20], and finally sent to Auschwitz and killed just after his 41st birthday. Confirmation came from the French government after the war, but my mother already knew. She didn’t tell me directly, but she intimated it to me. It took a long time to sink in.

At the end of the war the school returned to London and I with it. I was 14 years old by this time and I was once more put into a hostel for Jewish refugee children in Cricklewood [21]. Many of the other boys were already working and earning their keep. There was a girl’s hostel just down the road run by the same charity (B’nai B’rith [22]). It was from the boys’ hostel that I took my O and A Level school leaving exams [23]. We became British citizens. My mother finally escaped from domestic service and became manageress of a knitting wool shop. She had obeyed the restrictions on her original visa to the letter, and remained in resident domestic service for twelve years. One year later I became a conscript in the Royal Air Force, where I was able to learn quite a lot about radio, training as a mechanic. I had decided to try and get a university education and to that end I sought a job which would support me and allow me to get a part-time degree.

By this time it was 1951. My mother and I set up a home together in South Hampstead [24], the first time we had lived together since we left Vienna. I found a suitable job at the GEC [25] research labs in Wembley [26] and started the course for a mathematics degree part time, while contributing to our family income with my salary. All in all I spent eight years there, by which time I had not only graduated from London University, but gained knowledge of the upcoming speciality of computer programming.

It was during the latter part of my studies that I actively sought a partner. My mother gave me to understand that it must be a Jewish girl, and I kept that as a constraint. Soon after graduating I met a middle class girl from an Irish Jewish family of Lithuanian descent. Her father was a general practitioner in South London, as were many of their cousins and friends. We were engaged and married, starting a home in North London, first a flat in Archway [27] and then a little terraced house in Golders Green [28]. I changed jobs, to earn more money, becoming an engineer at the newly formed Electricity Generating Board [29] who had just purchased a computer.

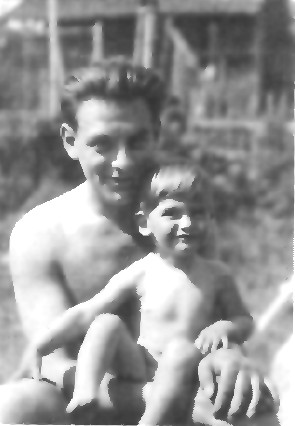

A child was born soon after we moved into the house. Money was tight, and I even did part-time teaching and lecturing in the evenings to eke out the budget. The job I had was one of the best paid available, but we couldn’t even afford to heat our house in winter and keep the baby warm. Then an opportunity arose to apply for a job abroad. The job was with CERN, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research, [30] who were just recruiting computer people like me. We packed up, rented the house out, and went to Geneva [31]. My mother was at the airport to see us off and she was seen to weep a little.

The job was fantastic, the place was beautiful, the work fascinating. Flats were available at reasonable rent, and didn’t need any capital. My wife Louise soon made us an active social life among the very clever mathematicians and their families, and in due course also among the American Physics professors on sabbatical leave in Europe. No language problem: everyone spoke English. We were learning French though. Our second son was born in Geneva. We had a wonderful life for five years, and only left because I was inundated with invitations from those American professors who wanted to recruit computer experts like me for their home institutions.

We packed up the Geneva operation, applied for the green cards [32] which went with the job, and moved to an American suburb just outside Chicago where we rented and then bought a suburban house. For the next five years we lived life in a mid-western suburb and our children went to grade school. My work became more and more successful; I was given extra responsibilities and the promotions that went with them, organised international conferences, and became well-known. At the height of my career, I was even invited back to Geneva to apply my new found experience to a large construction project: the control room of their new giant particle accelerator.

We sold our house, returned to Geneva, bought a flat, and put the children in the international school. I recruited a team and started on the new project. It took five years and it was even more successful than the ones in America. A French professor had invited me to write a PhD [33] thesis, and I registered at Strasbourg University [34], defending my thesis some years later. This finally qualified me as Dr. Beck, and a properly qualified scientist like my colleagues. My mother was proud when she received my telegram.

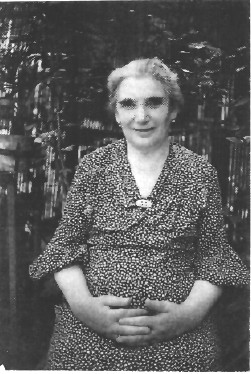

Our children went back to school in England, and we could see my mother and Louise’s parents on frequent visits to England. My poor mother wasn’t as lucky as we were; she was still effectively a refugee, though she did finally retrieve a pension from the Austrians enabling her to retire. She lived in a world of refugees and although she mastered English and read books in it for pleasure, she always had German, very cultured German, for her first language. We saw her often, and she came out to Geneva and had her holidays with us.

We stayed at CERN for about six years, and then I received another invitation to the USA, this time on a leave of absence. The children were studying in England and would visit us for vacations. I had various responsibilities as leader of a group providing services to experimenters, and we had the opportunity to enjoy working and playing with some very clever scientists. Several had been involved with the Manhattan project [35], and there were even Nobel Prize winners among them. After two years of this we decided not to stay in America; we would return to Switzerland, retire early and move back to England, where the children and the old folk were. We bought a flat in London and in 1990 we returned to England after an absence of nearly 30 years.

It was on our return to England that I became a refugee again. I joined the Association of Jewish Refugees [36], applied for Austrian pensions and an Austrian passport, and more importantly, we returned to spending our time with refugee friends from whom we had been separated for three decades, in an England which had changed immeasurably. During the next 13 years we had a wonderful retirement, and then Louise died of cancer. By this time the older generation were all dead. And I had survived.

Longevity is no joke. It goes with loneliness. I soon found a refugee lady whose husband had been on the Kindertransport. She rekindled my interest in studying and recording the Holocaust experience. I began to attend meetings with survivors and participated in the “Stones of Remembrance” project in Vienna. [37] The whole, horrible thing had happened. It must not be forgotten or, worse still, denied.

Frank Beck has done a lot of writing about his Holocaust experience including his two books “Grandpa’s Book” (ISBN 978-1291887594) and “Memoirs” (ISBN 978-1291850116) and several articles. Some of his articles can be found in the “AJR Archive” (see www.ajr.org.uk/pdfjournals), for example “A Motoring Adventure”, AJR journal December 2012, “Herr Schmutzer”, AJR journal July 2014 or “My Hungarian Cousins”, AJR journal March 2015.

[1] They followed the Jewish dietary laws. These traditional religious rules for the preparation and consumption of foods categorize food and drinks into kosher (yiddish for allowed) and trefa (yid. for not allowed).

[2] In 1939, registry offices were officially established and took over the keeping of the register from the religious authorities.

[3] The “Anschluss” refers to the annexation of Austria and its integration into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

[4] During April and Mai 1938, Jewish children were expelled from their schools and had to move to specials schools with only Jewish pupils and teachers.

[5] As one of the first Nazi concentration camps, this camp near the Bavarian city of Dachau opened in March 1933, originally intended to hold political prisoners. Until its liberation by the US Army in April 1945, more than 200,000 prisoners went through Dachau concentration camp, and more than 40,000 were murdered there.

[6] The Nazi term for the anti-Jewish pogroms which took place throughout the German Reich on 9/10 November 1938 is “Kristallnacht” or “Reichskristallnacht”. Its name, “The Night of Broken Glass”, refers to the many windows and shop fronts which were destroyed during that night. In addition to the looting, destruction and confiscation of Jewish businesses, apartments, synagogues and prayer houses, thousands of Jews were arrested. Some were deported to concentration camps, where many of them were murdered.

[7] A terminal railway station in the 15th District of Vienna.

[8] Between December 1938 and September 1939, around 10,000 Jewish children and young people escaped from the German Reich to Great Britain on so-called Kindertransports.

[9] Central railway station in London.

[10] Area of London.

[11] County in England northeast of London.

[12] Area of London.

[13] Area of London.

[14] Park in the North of London.

[15] Street in the London area of Hampstead.

[16] Abbots Langley is a large village in the county of Hertfordshire northwest of London.

[17] Minehead is a coastal town in the county of Somerset in South West England.

[18] A large town in the county of Essex with access to the North Sea.

[19] With the outbreak of World War II, France considered German citizens “enemy aliens” (“objets ennemis”) and put them into special detention camps, e.g. in Les Milles, Le Vernet or St. Cyprien.

[20] In the French city of Drancy near Paris a collection and transit camp was set up from where about 65,000 Jews were deported to the German death and extermination camps like Auschwitz-Birkenau.

[21] Area of London.

[22] Hebrew “Sons of the Covenant”: an international Jewish service and welfare organisation.

[23] O Level (Ordinary Level) and A Level (Advanced Level) are school-leaving and thus academic qualifications in England.

[24] Area of London.

[25] General Electric Company, a big business concern working in the fields of electronics, communications and engineering.

[26] Area of London.

[27] Area of London.

[28] Area of London.

[29] The Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB) was an important public institution for the British electricity industry responsible for the generation of electricity.

[30] Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire. This European research institution is based in Geneva (Switzerland) and was founded in 1954. It has 22 member states and runs the world’s largest particle physics laboratory.

[31] Town in southwest Switzerland on Lake Geneva situated near the Swiss-French border.

[32] Official documents issued to foreigners who want to work legally in the USA.

[33] Doctor of Philosophy: the terminal degree conferred by universities in many countries.

[34] Second largest university in France, situated in Strasbourg, a town in eastern France near the Franco-German border.

[35] This US military research and development project, carried out from 1942 to 1946, led to the production of the first nuclear weapons in 1945.

[36] This Association (AJR) was founded in 1941. Its main task is to support Jewish refugees in Great Britain.

[37] The aim of this project is to keep alive the memories of Jewish inhabitants of Vienna who were murdered by the National Socialists by placing so called “stones of remembrance” (certain plaques that indicate name, date of birth, date and place of death) in the pavement in front of the buildings where they lived.