Freddy Berdach

Survival

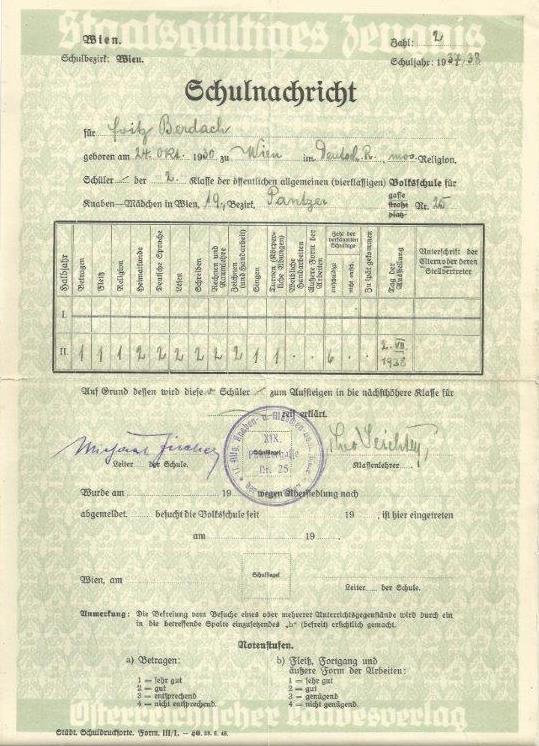

Freddy Berdach was born on 24 October 1930 in Vienna. After the “Anschluss” he and his parents had to emigrate because his family was Jewish. In December 1938 Freddy Berdach finally reached England, where he still lives today.

It is surprising what memories can be retained when the incidents are frighteningly fearful. It is over 70 years ago that my happy childhood was shattered by the entry of German troops into Vienna. It was a parade like no other. They marched along the main streets in their “Goose Step”, in their grey uniforms, with their swastika banners flying and bands playing. The Viennese population lined the streets – in many places six deep – cheering their saviours. From nowhere, swastika flags were suddenly flying from every building as if they had been expecting it. It really was a frightening time.

The “Anschluss” – the annexation of Austria – took place on 12 March 1938. [1] Anxiety, apprehension, hope against hope, intimidations, violence and fear swept through the Jewish population of Vienna. We were with our neighbours, listening to the radio, tense, wordless, nearing despair.

The “Anschluss” was sudden, savage and quite unprepared for. What had taken five years in Germany to tighten the screw on the Jewish people – getting worse every year – happened overnight in Austria. The fear among the Jews was palpable. My headmaster was prepared to throw me out of school the very next day. Our maid left us as soon as she had stolen all she could carry and the emerging local Nazi Party instructed us to leave our flat within two weeks.

Overnight we became fugitives. We stayed indoors. We no longer met with friends and relatives in coffee houses. My parents could no longer go to the opera, to the park or even the cinema. We began to search for another country. It filled our days for the next six months.

I became knowledgeable about how countries controlled emigration. I understood what a visa was, a quota [2], an affidavit [3], a guarantee. Some or all were needed to get in anywhere. Only one document was needed to get out – our agreement that we would willingly leave behind all that we owned. There was censorship and my father decided that the only way to get me and my mother out of Vienna was to go to Switzerland and apply for a British visa from there.

Incidents were happening all the time and men were disappearing overnight, mostly to Dachau [4]. One morning I was with my mother in our local delicatessen shop. The Jewish owner was well known in the district and dispensed his Jewish humour to all who would hear him. Suddenly two SS men [5], in their black uniform, marched in and demanded that the owner close his shop. Naturally, he was reluctant to do this when he had customers.

In those days, dry goods like lentils and rice were kept in sacks in front of the counter and wet goods like herrings and pickled cucumbers were kept in barrels, also in front of the counter. The two SS men then began to take the sacks into the street, slit open and empty the contents. They then took the barrels and emptied them into the gutter. Our genial deli owner was naturally upset and remonstrated with them. One of the SS officers took out his pistol and, in front of all the people there, including me, shot the owner.

Within a couple of weeks we were evicted from our apartment as it was needed for a “German” family. We moved in with my father’s parents into a small, cramped flat in the centre of Vienna. It was too much for my father and he decided to go to Zurich. My mother thought he was leaving us and could not understand my father’s intentions and cried her eyes out. When my father got to the Austro-Swiss border, they had closed it that day. He eventually “walked” over mountains to get to Zurich where he could write to get me and my mother a visa.

Our visa for England arrived in September and we had further anxieties to get our exit visa from the new Nazi Party in Austria. We had to obtain passports, duly stamped with a large J (for Jew) on the front. We had to have medical examinations and there were umpteen forms to be filled in. In every department there were long queues and – certainly for me – long waiting times. At last all these things were done. We had all the correct papers and we went to the station to get our railway tickets. We had a 24 hour visa for Switzerland before going on to England as we wanted to see my father before the next part of our journey.

We said our “goodbyes” to my grandparents and off we went – third class [6] – to Zurich. I was excited to be travelling to a foreign country and new city and I was beginning to be a chatterbox. Talking about all sorts of things I shouldn’t. I thought being on the train meant that we were already out of Austria. After an hour or so and my mother repeatedly telling me to be quiet, a German in civilian clothes, turned the lapel of his jacket to show that he was from the Nazi party, and asked me and my mother to accompany him. He took me into the toilet and gave me a strip search and searched my mother’s papers and travel bag. He found nothing wrong but it gave us both the fright of our lives.

We arrived in Zurich and were met by my father who took us to his digs where we were to spend the next four months. It was an idyllic time especially after the traumas of Vienna. Not only was the weather absolutely beautiful, but with Zurich being a lovely city, we were at peace with one another and with the world. I attended school for a few weeks and soon found one or two friends. All this was shattered one bright Saturday morning in December, when the Swiss police came to inform us that if we did not leave Switzerland within 24 hours, we would be taken back to the Austrian border. Of course my mother and I left the following day and so began our long train journey and rough sea crossing to England, where we arrived at Dover [7] on 20 December 1938.

The only reason we had managed to get a visa was because my mother would go into “service”, which she immediately did after Christmas. I was taken by the Jewish Board of Guardians [8] to be fostered by non-Jewish families. To make sure that I did not get emotionally attached to these families, they moved me every three months and so I had eight different families to contend with in two years. What was worse, they thought that as I couldn’t speak any English there was no point in sending me to school, so I missed three years of schooling.

My father reached England in August 1939 and in 1940 volunteered for the British Army and was sent to France with the British Expeditionary Force [9]. He was injured by enemy action and was sent home to be hospitalised for nine months. He was honourably discharged for his wounds and immediately became an “enemy alien” [10] – with all the restrictions that entailed, but this would be the first time that my parents and I were together since leaving Zurich.

I was sent to a wonderful convent school in Taunton [11], and those dedicated nuns taught me enough English in three months that I was able to go to a grammar school. My father, coming from a cultured city like Vienna couldn’t stand the small town of Taunton and we moved to London in 1943, with me transferring to a grammar school in Holloway [12]. We had a V1 (Doodlebug, a pilotless bomber) [13] fall in our front garden in May 1944, which made a bit of a mess of the house, but the fire brigade dug me out. We virtually lost all the little that we had and lived in Surrey [14] during the summer, returning to London in time for the autumn term. We had hardly settled back, when our flat was severely damaged by a V2 rocket.

We survived all that and were pleased to see the end of the war. I continued with school and made Matriculation in ten subjects, carrying on to A levels [15] which I passed in Chemistry, Physics Applied and Pure Maths. I was offered a place at King’s College [16], but the Deferment Board suggested that I should do my 18 months National Service first. Halfway through my time in the RAF [17], the Korean War [18] started and 18 months became two years. I would have to wait eight months for the start of the semester. I had to work as my parents couldn’t keep me and I never took up my university place. I never regretted not going to university, as within a couple of months of leaving the RAF, I met a wonderful girl with whom I fell in love and who I am married to – to this day.

I was lucky, having survived when so many didn’t and I thank God every day for my blessings. It was a horrible experience for a young person to go through and I never had a childhood. There is no way to make amends for murder and there is no way to make amends for the damage caused by persecution and expulsion but one hopes that the sufferings and sacrifices of all the people who were made to suffer have sharpened the senses to the ethical and moral responsibilities of the new Austrian generation.

[1] The “Anschluss” refers to the annexation of Austria and its integration into the German Reich on 13 March 1938 after German troops had entered Austria on 12 March 1938.

[2] Most of the destination countries for emigrants then had quotas which regulated how many immigrants they would admit to their countries.

[3] A document provided by a sponsor in a destination country, guaranteeing that the new arrival would not become a public welfare burden.

[4] As one of the first Nazi concentration camps, this camp near the Bavarian city of Dachau opened in March 1933, originally intended to hold political prisoners. By the time it was liberated by the US Army in April 1945, more than 200,000 prisoners went through Dachau concentration camp, and more than 40,000 were murdered there.

[5] The Schutzstaffel (SS), originally a small paramilitary formation of the Nazi Party, grew into one of the largest and most powerful organizations of the “Third Reich”, responsible for many crimes against humanity during World War II.

[6] Cheap and comfortless way of traveling by train. The third class had been abandoned in the 1950s throughout Europe.

[7] A town and ferry port in the County of Kent in South East England.

[8] A Jewish charity established in London in 1859.

[9] The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was sent to the Franco-Belgian border after the German invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939. Following the German Army's Blitzkrieg starting in May 1940, the BEF were pushed back and could eventually be evacuated from the French city of Dunkerque (Dunkirk) to England.

[10] With the outbreak of World War II, German and former Austrian citizens were declared “enemy aliens” and often put in special internment camps. Refugees who had enlisted in British troops – ironically called “The King’s Most Loyal Enemy Aliens” – were not interned.

[11] Main town of the County of Somerset situated in South East England.

[12] An area of London.

[13] The German V1 (Vergeltungswaffe 1 – “Vengeance Weapon 1”), built in 1944, was the first cruise missile and was widely used to carry out bomb raids on London. Later in 1944, the German V2, the first ballistic missile, began operation.

[14] County in Southern England.

[15] Advanced Level, highest school-leaving qualification in England.

[16] One of the most prestigious and renowned higher education institutions in Europe. King’s College is based in London.

[17] Royal Air Force, the British aerial warfare force.

[18] After World War II, Korea, having been liberated from Japanese occupation by the Soviet Union, was split into a northern communist and a southern capitalist region. In 1950, North Korean troops, supported by China and the Soviet Union, invaded South Korea which was assisted by the United States, thus starting the Korean War, the first armed conflict during the so-called Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. In 1953 fighting ceased, resulting in a state of stalemate and between three and four million military and civilian casualties.