Ilse Nusbaum

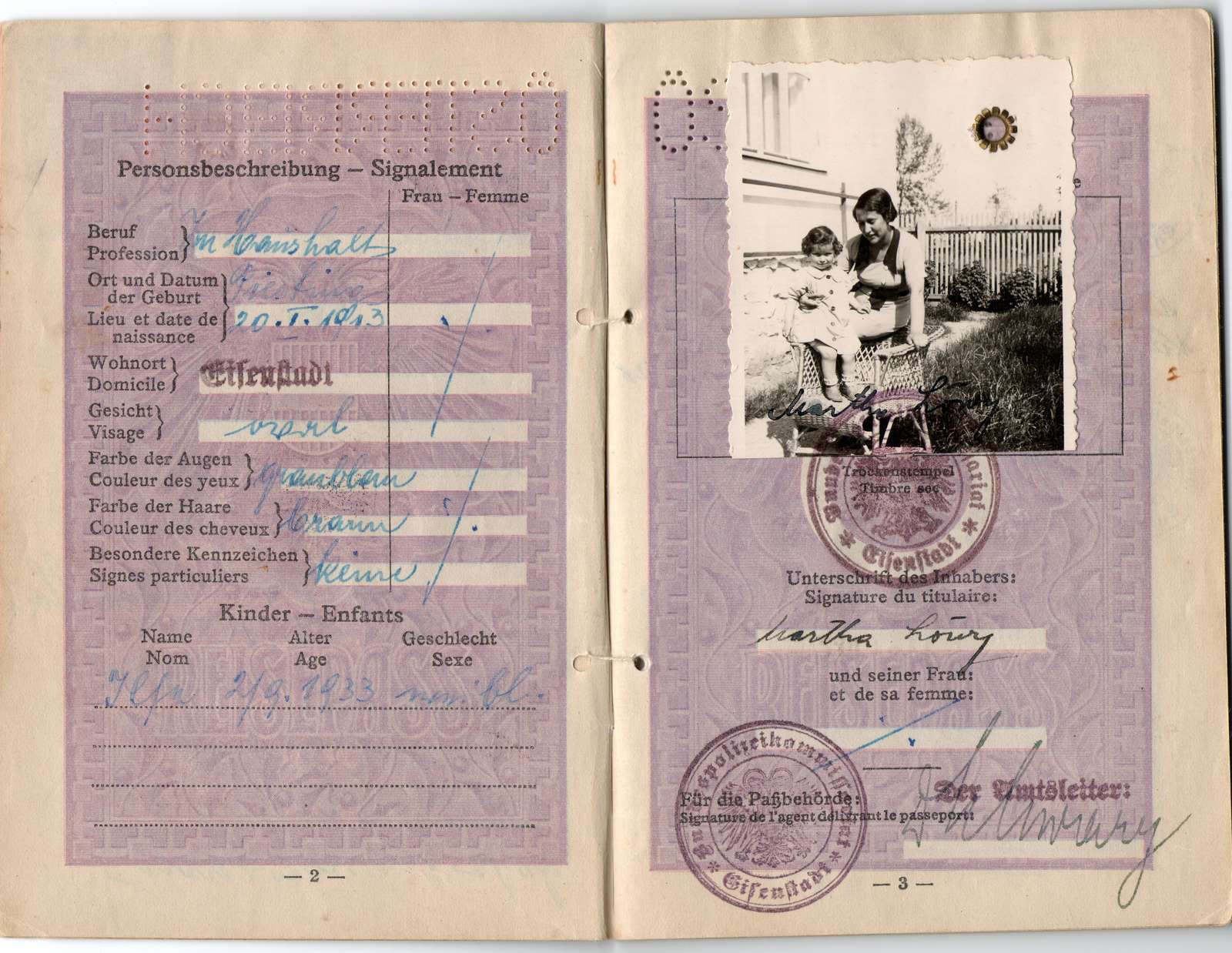

My father's dissertation

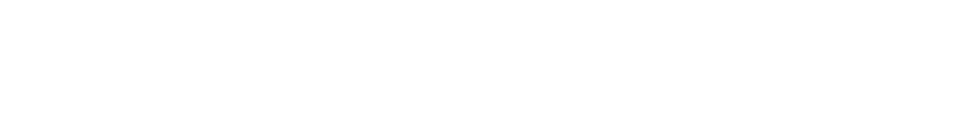

Ilse Nusbaum was born in Austria in 1933. She lived with her parents and her grandmother in Eisenstadt and had to leave Austria after the "Anschluss".

I was born Ilse Luzie Löwy in Wiener Neustadt on September 2, 1933. I lived in Eisenstadt [1] with my parents and paternal grandmother until after the "Anschluss" [2].

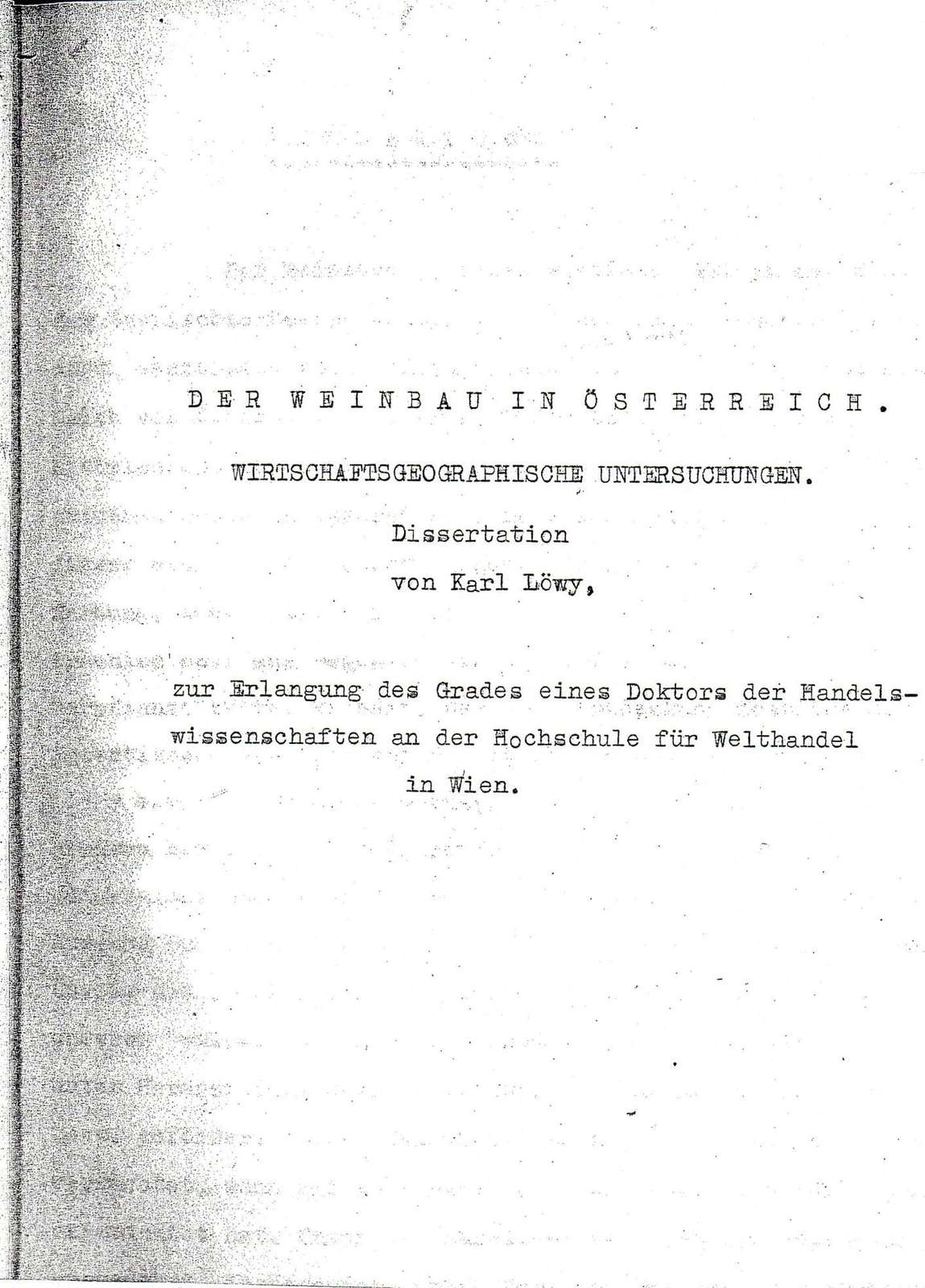

I have a rich Austrian heritage. My maternal family descends, through my mother's great-grandmother, Maria Schlesinger Braun, to the Court Jews [3] Marx and Moyses Schlesinger, and from them to the Rabbi called the Lebush. My father's father served in the Emperor's army during World War I and subsequently worked in the famous Wolf Winery in Eisenstadt [4]. My father taught at the Eisenstadt commercial college [5] as a "Diplomkaufmann" [6] and was due to receive his doctorate from what is now the Vienna University of Economics and Business [7]. His dissertation was accepted in January 1938, and he passed the examinations. The degree was to have been conferred June 1938.

In February 1938, my parents foresaw what was coming. My idyllic childhood was shattered on March 13, 1938. My father immediately lost his job and suffered an emotional breakdown. My mother was pregnant and concerned with obtaining necessary papers for our forced emigration. Gone was the everyday life of a normal 4-year-old.

We sailed to America on the SS Hamburg with visa numbers 581, 582 and 583, where we arrived in New York on May 20, 1938 – the fare paid from part of the proceeds of our stolen house. My Omas [9] were left behind. My paternal grandmother fled to live with a daughter in Yugoslavia, where she died. My maternal grandmother had been born in Sopron [10]. Though she'd lived in Austria most of her life and was the dentist in Piesting [11] (my grandfather was the doctor), she had to apply under the Hungarian quota. She took the train out of Vienna, headed toward London, on August 31, 1939. Her visa came through at the end of 1941, and she sailed on a Greek cargo ship, arriving in Canada in January 1942. My father's brother Ignatz was sent to Theresienstadt and from there to Auschwitz. The Nazis kept such meticulous records that the dates appear in a "Totenbuch" [12].

My parents were allowed to take $ 8 each out of Austria, which was the entry tax to America. Our sponsor, my father's sister, was surprised and none too happy to see that my mother was seven months pregnant. Detroit, where my aunt lived, was in the depth of the Depression. Unemployment was rampant, but she had lined up a job as a maid for my mother.

Being pregnant was bad enough – the first thing my mother did in America was skid on a rug and break her arm. I went off alone to Detroit with my resentful aunt, who hardly spoke my language and whose language, English, I did not at all understand. It was not a good welcome, but she could do no wrong in our eyes. We were saved from almost certain extermination.

My parents had intended to return to Vienna in 1970, to try to find out what became of my father's dissertation. He had a heart attack shortly before the planned visit. He didn't recover. Knowing that the Nazis had burned Jewish books as well as their authors if they were able, I was certain that the dissertation hadn't survived the "Anschluss" and war. Nevertheless, I occasionally googled his name and the title of the dissertation.

On November 9, 2009, I tried once again, this time putting in his name, Karl Löwy, and Burgenland. Up popped his dissertation! [13] It was in the library of the Vienna University of Economics and Business. I e-mailed the librarian, and she generously mailed me an entire copy. It was a wonderful gift.

Postscript

This story has a postscript. In September 2011, my daughter and I visited Vienna for a week as guests of the Jewish Welcome Service (JWS) [14]. We came on a mission, to obtain a doctorate for my father posthumously. My father, an instructor at the Municipal Commercial College in Eisenstadt, had been diligently working toward a doctorate in economics since March 11, 1931. His dissertation had been submitted. His "Meldungsbuch" [15] indicated that he'd passed his exams and fulfilled the requirements for the degree.

He started over in Detroit, earned a second master's degree at Wayne University, and became a certified public accountant. He had a successful career, but he never forgot about the degree that he'd lost. My parents had intended to return to Vienna in the autumn of 1970 to find out what had become of his dissertation. Airline tickets were purchased and travel plans made. It wasn't destined to be. He had a fatal heart attack shortly before they were scheduled to leave.

Knowing that the dissertation survived emboldened me to embark on a quest that may seem quixotic to you. I wanted the university to confer his diploma. I wanted justice for him, no matter how belated it came. I wrote to my contact at the Vienna University of Economics and Business in advance of our trip. She replied: "Please let me know what date and time you would like to visit the University of Economics library. I could arrange to have the original of your father's dissertation taken out from the archives so that it is at your disposal should you like to have a look into it."

I took advantage of the invitation. Did I mention that the events scheduled by the JWS were amazing? They were. On Wednesday afternoon, following a reception given by the president of Austria at the Hofburg, I telephoned the deputy library director. Fifteen minutes later, she met us at the tram stop and took us to the library. I couldn't have expected a warmer greeting. The director of the library and the archivist had retrieved the original copy of the dissertation. It was in excellent condition. The library's director offered to make a photocopy for the archives and give me the original. I was grateful for the generous offer, but declined. I believe the original belongs in the library's archives where it has safely remained for so many years. After I returned the book to its proper place on the shelf, we were directed to an index ledger where my father's name and the dissertation's title had been inscribed seven decades ago. Everything seemed to be exactly as it would've been had he received his degree, but it wasn't.

The photocopy I have at home doesn't show the back of the title page. If I hadn't looked at the original typescript, I wouldn't know that it's ink-stamped with a swastika. In the archives, I'd thumbed through another dissertation submitted before the "Anschluss". The back of its title page displayed a university seal with the Austrian coat of arms in the center, and two academic advisors had signed it. My father's professors hadn't signed his work. I know who they were. I know that they held onto their jobs. Of course, they'd distance themselves from my father and not sign his work. As for the swastika, even if it was imprinted for no other reason than to identify the book as university property, seeing it there shocked me. It is a grim reminder of those terrible years.

With the book safely returned to its place, our visit to the library ended, but that wasn't the end of the day. Our guide, the archivist, led us the few blocks to the old building where my father had studied. A short stroll took us there. The former name, Hochschule für Welthandel, still adorns its entrance, but it now houses the Vienna Institute for Archaeological Science (VIAS). We went inside and walked around, gazing at doors my father had entered when he was young. That evening, back at the hotel, I was handed a package. It contained both a photocopy and an electronic copy of the dissertation.

But this is a postscript, not the end of the story. It's my understanding that the official records of his candidacy will be searched for and reviewed. The legal department has been contacted. I hope that the university agrees that a posthumous degree would serve the cause of justice in academia. Whether or not it happens, I feel that I've accomplished something important for my brother, children, and grandchildren.

How a dissertation grew into a monument

The story of my father´s dissertation ended with a postscript. When I saw the swastika stamped on the back of the title page, I was determined not to let that be the last word. I asked the university to give my father a posthumous doctorate.

My request was denied on the grounds that he hadn´t successfully defended his dissertation. I pointed out that he hadn´t been permitted to take the exam. But a doctorate requires a dissertation´s successful defense, no matter what.

The matter eventually went to the Rector and historians who thoroughly researched the history of the university at the time of the "Anschluss". They discovered that my father was one of two doctoral candidates denied the degree after submitting their dissertations. In addition, about 150 other students were expelled - most of them murdered in the Holocaust.

To make amends, the university initiated a project that culminated in a monument on the new Campus of the WU and an on-line Memory Book [16] with the biographies of the expelled scholars. The monument was dedicated at a celebration on May 8, 2014. I was there to see it.

First publication of parts of this article in: Renate S. Meissner on behalf of the National Fund (Ed.): Lives Remembered. Life Stories of Victims of National Socialism, volume 2, Vienna, 2012, pages 130-137.

[1] Capital of the Burgenland.

[2] The "Anschluss" refers to the annexation of Austria and its integration into the German Reich on March 13, 1938.

[3] Court Jews ("Hofjuden"): Jewish businessmen or bankers who lent money to noble houses and were employed by them as financiers, suppliers, diplomats or trade delegates.

[4] The Wolfs, a family of wine merchants, was the most distinguished and prominent Jewish family in Eisenstadt.

[5] Städtische Kaufmännische Wirtschaftsschule in Eisenstadt.

[6] Business graduate; MBA.

[7] Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien (WU).

[8] "Clean of Jews" (Nazi terminology).

[9] Grannies.

[10] City in Western Hungary.

[11] Village in Lower Austria.

[12] Death Book.

[13] Karl Löwy, Der Weinbau in Österreich. Wirtschaftsgeografische Untersuchungen, Wien, Univ.-Diss. 1938.

[14] The Jewish Welcome Service (JWS) was founded in 1980. JWS has made it possible for thousands of former Vienna residents who were expelled from Austria in 1938 to visit their former home town. For more information see www.jewish-welcome.at.

[15] Report book.

[16] Memorial Book for Victims of National Socialism at the Hochschule für Welthandel 1938-1945/Gedenkbuch für die Opfer des Nationalsozialismus an der Hochschule für Welthandel 1938-1945.