Kurt Flussmann

Stations of my life

Kurt Flussmann was born on 19th January 1923 in Vienna. In January 1939, he arrived in Great Britain on a Kindertransport. In 1940, he was deported from Britain to Australia as an "enemy alien".

My name is Kurt Flussmann. I was born in Vienna in 1923. Now, in my old age, I have decided to put down my story in writing, because I think it is important that what my generation has lived through will never be forgotten ..

Childhood

My parents had already separated before I was born and each had a new partner. I lived with my aunts, Paula and Camilla, two of my father's sisters, who – although both over 50 – took care of me. When I was naughty, I remember they used to call me "Kurti". I remember that Aunt Paula used to like playing Halma with me and she always won. Although my aunts were very loving, I nevertheless missed that feeling of security which, in my opinion, only parents can provide.

When I think back to my parents, I can remember that my mother worked a great deal. She was very attached to my grandmother and helped her out in her grocery store in Ottakring [1]. She was a very hard working and capable woman. She always seemed to be busy. My father worked in the travel agent's, Schenker & Co. He often went on business trips to Italy and traveled a great deal. My father was a thoughtful person and I remember him being strong and powerful. There was little communication between us and, in truth, I was scared of him. As a child, I took turns living with my mother for two days in the 16th district and then two days living near my father with my aunts in order to maintain contact with both. It was a constant to-ing and fro-ing. However, it was left to my aunts to raise me.

I attended elementary school in the 2nd district of Vienna and four years of high school. I was not a particularly good student and I found it difficult to learn. Geography and history appealed to me the most. After school, in accordance with the wishes of my father, I attended an international hotel management school which was situated in Kurrentgasse in the 1st district. Father wanted me to work in a hotel business in Italy one day. But fate had other ideas.

Teenage years

Everything changed when the Germans marched in on 12th March 1938. They were uncertain times and my family could think of nothing else but how they could get me out of the country to safety.

One of my aunts worked at the Jewish Community. Thanks to her good relationship with an acquaintance, who was also employed there, she was able to get me on the list for the Kindertransports to England. For a whole year, my aunts prepared me for the fact that I would have to go to my Aunt Eva in England. She would make sure that nothing happened to me. Of course I was aware of the pressure and fear during this time, but I was young and still relatively carefree and didn't know what lay ahead of me.

Sometimes my aunts sent me to a Mrs. Siegel in Novaragasse with a basket of eggs. My aunts took care of the elderly lady and often sent her little bits and pieces. It was a fifteen minute walk, and I was very careful of the valuable eggs. I didn't look left or right, I just tried to complete my journey as quickly as possible. Mrs. Siegel did card readings – and she had predicted me a lively and active future. I would go on long journeys, she said. Of course, no one could have known just how right she was…

Finally, in January 1939, a week before my 16th birthday, I was secretly brought to the station Westbahnhof, where many other children and teenagers had gathered. Everything was done very quickly and with the greatest care. My aunts once more drummed into me that I should be good, and the farewell from my parents was brief and composed in order to avoid becoming too emotional. At this time, all contact with my relatives in Vienna was lost.

I was on my way to a completely unknown future, equipped with only the bare necessities, in a little knapsack. The train journey took us via Holland to the port Hoek van Holland [2] and from there we traveled to Harwich on the East Coast of England on a Dutch ship. It was my first ever journey on a ship and I was incredibly impressed. We were then taken from Harwich to London by train. Aunt Eva, my father's third sister, had emigrated to England from Romania and was waiting for me at the station. As we hadn't met each other before, my name was called out. Like all the children, I had a sign round my neck on which my name and my destination were written.

Aunt Eva had a small boarding house in London, where I now lived in a guest room. It was the first time I had had my own room. Initially, I stayed inside most of the time, going out only for short walks or trips to the cinema. My aunt had English guests in the house, to whom she served breakfast and small meals. She was very busy. As I had already learned to speak English well at school, I soon settled in. Aunt Camilla was able to follow me from Vienna a few months later. Aunt Paula didn't manage …

I soon got an apprenticeship with a jeweler, Mr. Joe Freeman. However, he only let me do work which had nothing to do with the jewelry profession. He mainly used me as an errand boy. I delivered personal documents from my boss, who had started to transfer valuables to America, to the American Embassy. I didn't learn anything relevant to the profession so, feeling superfluous, I gave up the apprenticeship. In 1939, I got a temporary job at a hotel on the East Coast, in Eastbourne, in Folkstone near Dover. I remained there until my internment on 10th May 1940 [3].

In June 1940, I was picked up from breakfast and brought to Liverpool in a great hurry by two officials, along with other refugees. Transports were put together which were to take us out of the country. My aunts had no idea – all contact was broken. I was given no information either and was simply carried off like a prisoner. The transports were to either go to Canada or to the Isle of Man [4]. Unknown to me however, my ship, the "Dunera", was the only one to sail to Australia.

The journey

The English loaded us on to the "Dunera" like criminals. With just a toothbrush and the bare necessities. To reassure us, they promised us that we would be back soon. On 10th July 1940, the "Dunera" left Liverpool.

Apart from us refugees, there were also Italian and German prisoners of war on board. We were penned in below deck and for two months were not allowed up on deck; the English guarded us with their bayonets at the ready. We had to relieve ourselves on the floor. I slept for the whole journey on a table. The food was brought to us by sailors. We were so terrified, we had no self-esteem left. It was miserable. Not only due to the constant fear that we would be torpedoed and sunk, but we also had no idea how long the journey would last and where we were going. Now and then, we were allowed up on deck, but that was all. We were held like prisoners. We were completely helpless.

When it started to get warmer on the ship, after eight days, we were finally told that we were not on our way to Canada but to Australia. The passage to Canada had been too dangerous. Another ship [5], which had departed a week before us, had sunk with 1,200 people on board after being hit by a torpedo. That was a great shock.

The mood among my fellow travelers was very subdued. We consisted solely of men aged between 16 and 60. A few were seriously ill and segregated from us. The first stopover was in Sierra Leone on the West Coast of Africa. Of course, we were not allowed above board, and so it was through a porthole that I caught a glimpse of an African for the first time in my life.

In Perth, Western Australia, the Italians and the Germans were finally allowed to disembark and the majority of the refugees, who were being awaited by relatives, were allowed off in Melbourne. For me and the remainder of the travelers, a few hundred people, the journey continued to Sydney. On 6th September 1940, we were finally received there by the Red Cross, which was waiting with food parcels.

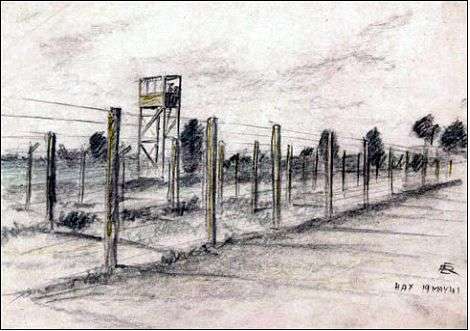

We were then rounded up for a further transport and I was sent to New South Wales, where several camps had already been set up at the desert station Hay. A few thousand people lived here. For 33 months, we weren't permitted to leave the camp. They imprisoned us behind barbed wire as "prisoners of war".

Camp life

The atmosphere in the camp was depressing. Our future was uncertain and we lived from "day to day" without plans or things to do. There were 18 people in each barrack. The dining hall and the camp management were located in one big barrack and the sports field was in the middle of the camp. The days had little structure. The only activity strictly adhered to was the "9 o'clock parade" in the morning. Although we weren't woken up especially, it was clear that we were to appear dressed and punctually for the parade, which was held by Lieutenant O'Neil, a half-Australian. Each day we were counted, always the same ritual. Then, for the rest of the day, there was nothing to do. We just vegetated, without purpose or foreseeable end. Modest opportunities to do some sport, handball or football, were offered if we fancied a change. We were able to play chess, make music or we chatted amongst ourselves.

One time, we put on a show. The title was "Say Hay for Happy and you be Happy in Hay". This show was above all about happiness and laughing. It entertained us and lifted our morale. The camp inhabitants performed, sang and made music. It was very successful.

Then Major Leighton from England arrived at camp Hay and tried to put an end to our unjust fate. He was, so to speak, the mouthpiece of the English government. He was our advocate. Dr. Gelis, a lawyer, was also employed as liaison officer and tried to mediate between the camp management, Major Leighton and us inmates. He tried to settle our future. All those who were married and had families or children were allowed to return to their relatives in England. That was in spring 1941. I also considered returning but it seemed too dangerous. I didn't know what would await me during the passage or in England.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Major Leighton had a work camp set up in Tatura in the state of Victoria to where we moved on his advice in 1943. The climate and the surroundings were better and healthier for us there. We could do gardening and grew vegetables ourselves, which we then gave to the kitchens.

An incident occurs to me when I hear the song "Brüderlein fein". Mr. Georg Willner, an old man, always buoyed me up: "Brother, just stick it out, it will all be okay in the end", he often consoled me

In order to escape further inactivity, after 33 seemingly endless months I decided to join the work battalion. I wasn't really working voluntarily in this battalion but what else could I have done? But when I saw that more and more people were joining the work battalion, I went with them. I was about 19 years old – at the time I couldn't see any other alternative.

We worked for an Australian fruit grower, who also accommodated us, and we picked oranges and peaches to prepare ourselves for life after the camp and to get used to freedom. Then we were sent to the Australian army, the Pioneer Corps, which had been set up by the government and our work battalion received the uniform of the Australian army. The train tracks had different gauges in each Australian state, and our task was to carry the heavy boxes of ammunition from one set of train tracks to another in the border area between Albury and Victoria. Depending on the demand, we often worked for many hours on end.

Through the Red Cross, I heard in Victoria that my father and his partner had been deported from France to Auschwitz in 1943. That was all I heard of my relatives during this time.

After one and a half years, I was classified as unfit for service – I suffered from depression – and was honorably discharged from the Australian army. After my release, I tried as a 20-year-old to find my feet in Melbourne, which I didn't really manage. I found a job at a wine company called "Winn's Wines", where on one occasion I carried some heavy loads. Again, I had to stop due to my health.

After the war – Sydney – London – Vienna

In 1945, I went to Sydney and lived as a sub-tenant with a married couple from New Zealand. I thought it would do me good and worked for a few months at the post office and sorted the letters. And then I again fell into a deep depression. I fell into a hole, so to speak, a sort of paralysis. I was treated with electric shock therapy and valium – there wasn't any other treatment back then. The depression had begun during my camp and army time but now it had become particularly bad.

As I didn't want to become an Australian citizen, I was sent back to Great Britain in 1947. It was a great relief to meet with my aunt when I arrived and to see that she had survived unscathed. We were both surprised and overjoyed to see each other again! I remember traveling through London on a double-decker bus and seeing all the destruction. The years had also left traces of destruction on my soul. At the age of 23 there was and remained permanent damage to my health. The depression continued to return. In the Australian camp, the hopelessness led to the state of mind that "life had passed me by" and this contributed to my resignation. I didn't have any influence over my life. Things happened and I could only let them. There wasn't anybody with whom I could talk and that led me to a kind of "inner emigration" which I never completely escaped.

In 1948, Mr. Flussmann traveled to Germany to work there as a translator. In the same year, he also found his mother, who had survived the war in Belgium. He often visited her there until her death in 1978. His father had been murdered in Auschwitz. In 1952, Mr. Flussmann left Great Britain for the last time. From 1952, he worked as a sailor on freight ships and oil tankers in Europe and overseas and he worked in service as a steward. He spent the winters on the Canary Islands. The sailor's house "Scandia" in Antwerp where Mr. Flussmann often lived after being at sea was closed down, thus putting an end to his voyages in 1961. In the same year he returned to Austria.

I didn't know anyone in Vienna either, for I had left as a young man. Wherever I went, I remained without a homeland and without roots. The feeling of not belonging anywhere stayed with me. Just as in my childhood…

Looking back

Today, as a sick, old man, I have to say that I found my life to be a difficult enterprise. I could never be relaxed in making decisions, was existentially always under pressure to make a move and my opportunities were limited. Subsequently, I stopped making plans. I lived my life in the moment. A life spent constantly trying to survive.

I often met people, thank goodness, who were touched by my story and who then helped me. But I always remained reliant on whatever help was given – and continue to be today.

Even today, looking back, I don't think that I could have done anything differently. My life hit a dead end that I struggled to overcome. It was a ruined life. That's how I see it today…

Nevertheless, the good Lord was merciful to me. He showed me the whole world: I was in Russia, America, Canada, South America, Brazil, and many other places. However, fear and pressure were my constant companions, wherever I found myself. Prof. Hamburger, my doctor in Amsterdam, once said to me: "You will never be rid of the barbed wire in your head…".

Mr. Flussmann has been living in the Sanatorium Maimonides Center, a Jewish retirement home in Vienna, since 1981. His greatest wish is to once more visit the grave of his mother in Putte (Belgium), who is buried there in the Jewish cemetery "Frechie Stichting".

The life story of Mr. Flussmann was recorded during the psychotherapeutical work of Franziska Berger of the Consiliar Liaison Team at the ESRA psychosocial center in Vienna. The abridged version that is published here was compiled by editors at the National Fund.

More information on the work of ESRA you can find on the website of ESRA.

First publication of this article in: Renate S. Meissner on behalf of the National Fund (Ed.): Lives Remembered. Life Stories of Victims of National Socialism. Vienna, 2010, pages 130-139.

[1] 16th District of Vienna.

[2] Today an area of Rotterdam.

[3] Mr. Flussmann was interned as "enemy alien". With the outbreak of WW II, German and former Austrian, later also Italian citizens were declared "enemy aliens" and put in special internment camps.

[4] The biggest internment camp for enemy aliens was located there.

[5] The "Arandora Star".