Ladislaus Gelb

The Life and Times of Leslie Gelb

Shortly before Ladislaus Gelb died he was interviewed by some individuals who were interested in his life story. The result is a wonderful story written by Jonathan Soles and Ruth-Ellen Soles (Toronto, Canada).

Free at First

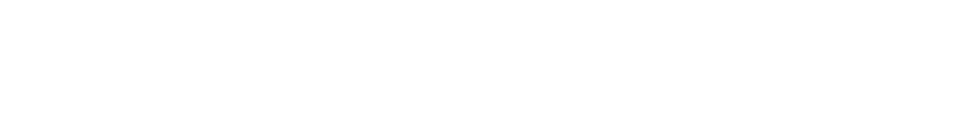

Ladislaus (Laci) Gelb entered this world on 8 July 1917 in the waning days of the Great War and the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Vienna. His mother Helen (née Gehorsam) was a native of Prague and his father Gustav was born in Budapest. The couple had lived in several cities (their first child, Hans, having been born in Trieste five years earlier), but they chose Vienna as their home.

Gustav worked in a senior executive capacity for a large bank, spoke five languages, and was a respected member of the community. He provided his family with a fine home in a fine neighbourhood complete with a maid, a chauffeur, and a cook. The bank provided a car.

The Gelbs were upper middle-class, Jewish, and thoroughly assimilated into polite society. They celebrated Passover [1] with the local Chapter of B'nai B'rith [2] because Gustav sat on its board, but they were neither members of a synagogue nor observant followers of their faith. The Gelbs considered themselves Austrians who just happened to be Jewish, and Laci was agnostic from day one.

One day when he was just ten or eleven years old, Laci was walking to school and passed a motorcycle shop where repairs were being made on the street outside. The young man was so overwhelmed by curiosity that he spent the entire day learning how to disassemble and reassemble a motor bike. From that day forward he was inclined in general towards all things mechanical and to motorcycles in particular. At twelve he decided to drive the family car, a Steyr, around the garage all on his own. At age 15 he bought his first bike, a two-stroke 200cc Puch paid for on an instalment basis. For his act of truancy at age eleven Laci caught hell from his parents, but that choice was later to save their lives.

Untermenschen [3]

By the time Laci was studying engineering at technical college in Vienna, Germany was being run by an Austrian. In the mid-1930s, visiting American clientele urged Gustav to emigrate with his family to the United States before it was too late, but he demurred. He felt he had too much to lose and, furthermore, he believed that despite Nazi posturing, Austria's sovereignty was guaranteed. Indeed, the union of Germany and Austria was prohibited by Britain, France, and Italy under the terms of both the Treaties of Versailles and Saint-Germain. [4]

On 12 March 1938, shock swept over the Gelbs when, without a shot being fired, Hitler's army strolled into Austria where it was greeted by cheering crowds and fêted with flowers. […]

Anti-Semitism was stronger and more hidden in Austria than it was in Germany, and while it may have been incomprehensible to Austrian Jewry that citizens of all ranks would so thoroughly and quickly embrace Hitler, the transformation was a fait accompli and the ravaging effects of it immediate and brutal.

The next day Gustav was sacked by his employer. Within a week he'd surrendered all his personal possessions, including his house, to ensure his family's safety. The Nazis had detailed lists of all assets held by every wealthy Jew in the country. The Gelbs were prohibited from retaining their domestic staff. Their car was stolen by a nearby shoemaker's apprentice. Laci, who had just completed his engineering degree, was refused his certificate. Helen was forcibly removed from the house and made to scrub the sidewalk for the amusement of thugs sporting Nazi armbands. To avoid arrest and the threat of violence the family sought shelter in a different place each night.

Flight

The Gelbs' sole hope for salvation lay with Hans who had left Austria for the greener pastures of England two years earlier. Their challenge was two-fold: first, they had to persuade the Nazis to let them leave Austria; second, Hans had to persuade the English to permit them entry. The former problem was a Catch-22, the latter a virtual impossibility. Nazi policy allowed Jews to emigrate only after they had surrendered their wealth to the state which would deprive them of the resources necessary for travel and bribes. Meanwhile, by 1938 the British government had drastically limited access to refugees from the continent, particularly to Jews. […]

Despite being a superb negotiator, Hans could manage only a single six-month entry visa and Laci, still under a student deferment from active service, failed to obtain exit papers after queuing for 48 hours at a government edifice. In desperation, Gustav risked bribing a Nazi lawyer and it paid off. The next day Laci's exit visa was processed by the same Nazi official who had initially refused. However, the dispensation automatically annulled the boy's deferment from active service which meant he would have to petition the War Office to release him from duty. Laci was terrified at the prospect of making such a request, but in a surreal turn of events the approximately 35-year-old Gestapo officer responsible approved the request wistfully declaring "I wish I could go with you" as he did so.

Enemy Alien

So far so good, but how to actually get to Britain, for should Laci have attempted to travel through Nazi-occupied territory he risked being rounded up in accordance with the Party's Nuremberg Laws [5]. Surface routes were too dangerous so Gustav, Helen, and Laci's best friend accompanied the lad to the Vienna airport on 29 August 1938 and watched him board an eight-passenger Sabena Airlines [6] aircraft bound for England by way of Belgium. When Laci landed at the Croydon Airport [7] he was a physical and emotional wreck. His brother met the plane. The 21-year-old had 10 Marks to his name (about enough money to buy a sandwich), didn't speak a word of English, and didn't know if he would ever see his parents again, but at least he was a free man – or so he thought.

Immediately upon his arrival in England the young Austrian was made to report to the Criminal Investigation Department of the Home Office for purposes of registration. There he was deemed an "enemy alien" [8], a classification that prohibited all study and employment. The two brothers then travelled to Birmingham where Hans shared a house with several young engineers. Laci became acclimated to his new surroundings within a few weeks. Throughout his time in England he found most people respectful, helpful, and kind, and he encountered very little overt anti-Semitism.

While work for foreigners was scarce, Hans had less trouble finding jobs than he did keeping them. Initially, Laci had to do odd jobs for which he could be paid under the table. For a time he played piano in a local tea room. Soon he found steady work building custom cars for half wages at Jensen Motors, Ltd. in West Bromwich some 15 miles away. He worked as an assemblyman underneath the vehicles. On his first day of making the commute to work by train he was dismayed by England's aged railway infrastructure and disgusted by the spit under foot everywhere on the platform. He recalls feeling, at the outset of that journey, a sense of pride for his more modern and "civilized" birthplace; a feeling he cut short in an instant.

The brothers chose to speak only English in their adopted country. […] In the early going Laci experienced some difficulty penetrating the thickness of the Midlands accent. Within six weeks his English was passable, but it took some time for him to discern high English from low given the coarseness of the vernacular spoken on the shop floor. To wit, one night at a fancy dinner party he employed the phrases "bloody lovely garden", and "time to bugger off". However, within eight weeks young Laci's English had improved significantly thanks to a facility for language and to the assistance of his new best friend and housemate, the well-educated John Dunlop who worked at a nearby steel plant. The two had become fast friends owing to their mutual passion for motorcycles! The linguistic role-reversal completed, his Jensen factory co-workers didn't know what to make of him when, upon finding a stray tool at his bench, he openly inquired, "to whom does this belong?"

It should be noted that to the English ear the name Laci sounded like "Leslie" and that from the outset Les gave over to the Anglicization of his name. Hans had taken the name John upon his arrival in England.

Reunion

Of course the Gelb brothers were desperate to get their parents out of Austria. The boys were in occasional contact with Helen and Gustav by post so they knew that circumstances in Vienna were deteriorating and they feared the worst. On several occasions Les took the train to London to plead for assistance from B'nai B'rith and was appalled by their refusal to do anything; Gustav's earlier standing in and generosity towards that organization mattered for nothing. Though they knocked on every door and turned over every stone the boys could find no way to help their mother and father escape the continental Europe.

In December, John Dunlop (who was well aware of the Gelb's predicament) invited Les to join his family in London for Christmas. During the visit John's father, Sir Thomas, peppered Les with questions about his parents. In Birmingham some months later, Mr. Dunlop asked for further details about them. On neither occasion did he explain why. It turned out that the senior Dunlop was a high-ranking diplomat with the Foreign Office and that his primary duty was oversight of Britain's embassies on the continent. Based on the information provided by Les, Sir Thomas instructed the British Ambassador in Austria to find the Gelbs and get them out, a remarkable feat that was accomplished just a few weeks before the outbreak of war.

Several months prior to the surprise arrival of their parents, Hans and Les had moved from Birmingham to the sea-side town of Hove just outside Brighton where Hans had found them a better job at a machine tool company. Later, Hans found them an even better job in London designing engraving machinery for a company under contract to the War Department. Les's abilities were so highly prized by his superiors that they gave him a car to make the commute. Les and Hans met their parents in London and returned with them to Hove for a joyous reunion. Shortly thereafter the two brothers bought a modest house in which all four of them lived as a family again, but they were not to enjoy each other's company for long.

Collar the Lot [9]

On 11 May 1940, in anticipation of invasion and fear of fifth-columnists, Winston Churchill's first act as Prime Minister was to order the arrest and internment of all potentially dangerous German and Austrian nationals residing in Britain. Beginning in October the previous year, 120 one-man tribunals had traversed the country classifying these persons into three categories: A) deemed suspect and to be interned (600); B) at liberty, but subject to restrictions (6,800); C) initially exempt from internment or restriction (64,000). While Les was never officially informed of his classification, clearly he had been deemed a Category "C" internee by a Hove County Judge that autumn.

Arrests began on 12 May. By 30 May, 9,000 had been interned and the net was widening. […] By the end of July some 30,000 refugees from Nazi oppression had been rounded up. Three-quarters of those interned were Jewish and nearly half of them were under the age of 25. Initially, the internees were sent to one of six camps: Bury St. Edmunds (Suffolk), Kempton Park Race Course (London), Seaton (Devon), Warth Mill (Lancashire), Huyton (Liverpool), and Lingfield (Sussex). Reports of internees being verbally abused and spat upon by civilians were commonplace at all of them. These makeshift camps were used mainly as staging areas while the prime holding facility on the Isle of Man was being readied. Transfers to the Isle of Man began on 2 June […].

On 27 May 1940, a beautiful, sunny Sunday, two plain-clothed detectives called at the Gelb house in Hove. Les and Hans were asked to accompany them to the station house for routine questioning in what the police claimed was to be a short stay and "a minor inconvenience". They suggested the boys might like to bring along a toothbrush just in case, but the brothers brought nothing nor would they have been allowed to if they'd tried. They were not taken to the police station, but to the Brighton Race Course to join a number of other "enemy aliens" already in custody. While there Les and Hans learned that they were among the last to be picked up.

Shortly thereafter the group in Brighton was transported to the Huyton camp, a number of empty huts surrounded by barbed wire. Upon learning what had happened, Les's boss, the co-owner of the engraving firm, tried in vain to have him freed.

Perhaps the sole benefit to being interned in such a way was the quality of the company, many being accomplished professionals of the sort a young man would never normally have the chance to meet. For example, Les chatted at length with some senior executives formerly with UFA, the principal German film studio of the day.

After a week at Huyton the internees were shipped to the Isle of Man and held for a month. During this five week period they were given no indication as to why they had been arrested or how long they would be interned. They were poorly housed, wretchedly fed, and denied any contact with the outside world. In fact, it wasn't until the three-month mark of their internment that they were allowed to contact their families. The form of that contact was a postcard, issued by the Red Cross, with the single phrase "I Am Alive" pre-printed on it to which they were prohibited from adding anything but their name.

Many months later Les and Hans learned that their parents had been arrested several days after they themselves had been picked up. After a short stay in police custody, Helen and Gustav were evicted from the house in Hove, for no "enemy alien" was permitted to live within 200 feet of the English coastline. Their house, furniture, and belongings had been auctioned off with all the proceeds being directed to the state. Once again the elder Gelbs had been forced to rely on the kindness of others for their very survival.

An Error of Omission

Working feverishly to free up men and material for the invasion they believed to be imminent, Churchill and his War Cabinet sought […] to deport both Nazi prisoners of war (POW) and internees to the Dominions: Canada and Australia agreed, New Zealand and South Africa refused. […] The Canadian government agreed to the transfer of 7,000 men […].

It is regrettable, perhaps even unforgivable, that the British authorities did not explain to Canadian authorities the differences between the three internee categories. Unaware of these distinctions the Canadian government assumed that all the men were equally dangerous. This assumption was further entrenched by the fact that the first group to arrive in Canada included a number of genuinely dangerous men […].

Hell on the High Seas

On 30 June 1940 the internees on the Isle of Man were shipped to the Port of Liverpool and made to remain on the jetty under guard. By the time they were prodded towards the Arandora Star, the first of three vessels put on to transport them to Canada, it was the middle of the night and they had been 30 hours without food. The scene was chaotic, the internees being herded about like cattle. Les and Hans were halfway up the gangplank when word came down that the ship was filled to capacity. At the time the two brothers were completely ignorant as to the name of the vessel or its intended destination and they were so exhausted, hungry, and demoralized that they didn't care. Eventually they would come to realize just how lucky they had been.

The Arandora Star, formerly a Blue Star luxury liner, sailed for Quebec City by way of the Irish Sea at 4:00 am on 2 July carrying 473 Category A internees, 717 Italians, and a crew of 400 including a compliment of British soldiers. At 6:58 am she was struck amidships by a torpedo and sank in 30 minutes. The loss of life was considerable: 833 men including approximately 600 internees […]. U-Boat 47, under the command of Günther Prien, "The Bull of Scapa Flow", had been headed home in triumph after sinking eight ships including the battleship HMS Royal Oak. When he sighted the Arandora Star Prien had but one torpedo left in his arsenal. The survivors were rescued by the Canadian destroyer HMCS St. Laurent and returned to Liverpool. Eight days later 450 of them were loaded aboard the Dunera bound for Australia. […] The Dunera was fired upon by another U-Boat very near the same spot as the Arandora Star was attacked, but due to the exceptional skill of her captain she reached her destination unscathed.

Neither Les nor Hans were aware of the fate of the Arandora Star when they, along with 785 POWs, 1,308 Category B and C internees, and 405 Italians, boarded the Ettrick bound for Quebec City on 3 July 1940. Their nightmarish voyage to Canada was to last ten days. The German POWs were allotted the first and second class cabins on the upper decks while the internees were crowded into steerage. Compartments designated for 48 men were made to accommodate 150. The internees were not permitted topside and were locked up at night. They were denied fresh air altogether although they managed to forcibly open a couple of small portholes. They were fed little, slept in hammocks stacked one above the other, and endured deplorable hygiene while the POWs above them, their morale high, took in the sea air and sung songs such as "When Jewish Blood Drips from Our Knives, Things Go Twice As Well".

A few days into the crossing a diarrhoea epidemic broke out below decks and lasted for two days. The younger men, including Les and Hans, were quickly organized into a "bucket brigade" by the most famous internee to be deported to the Dominions: Prince Friedrich Georg Wilhelm Christoph von Preußen, or Count Fritz Lingen as he preferred to be known, youngest son of the Crown Prince of Germany and grandson of the Kaiser. For this Lingen earned the nick-name "Prinz von Clean". Les remembers Lingen as a kind man who assumed no airs and who gave no indication of being an anti-Semite. Ironically, Lingen had answered the Fatherland's first call in 1938 and participated in the "Anschluss" [10] as a member of the Wehrmacht's Tank Corps.

On the morning of 14 July, as the Ettrick cruised down the Saint Lawrence River under clear skies, the internees were assembled on deck for the first time since having boarded the vessel. Breathing the fresh air, basking in the sunlight, surveying a new and unknown country they enjoyed a brief period of elation, but were soon returned to a state of anguish by their hunger, fatigue, and dysentery, exacerbated by severe taunting from the Nazi POWs. It didn't help that they were kept on deck for many hours with no food. When they finally disembarked at Wolfe's Cove beneath Quebec City it was 8:00 pm and some of the men simply passed out from exhaustion. Les remembers feeling like a mindless animal, completely disconnected from his humanity. He'd been traumatized by the crossing and had developed claustrophobia from the experience, an ailment from which he has never recovered. If he had been able to think clearly he might have thought the worst was behind him, but he'd have been wrong.

[…] On 10 July all transfers of civilian internees to the Dominions were discontinued. […] The release of internees in England began in August and by April 1941 only 1,300 of 30,000 remained behind barbed wire. [11] […]

You'll Get Used to It

The internee's first experience in Canada was to be thieved at the hands of the authorities. After they were searched on the pier at Wolfe's Cove, their luggage was confiscated and receipts were issued – during their internment in England, Les and Hans had been sent some clothes, toiletries, and luggage by their ever-resourceful parents.

They were then bussed to Camp "L", a temporary facility consisting of white huts surrounded by barbed wire and machine gun positions situated on the Plains of Abraham. There they were searched again and inspected for venereal disease. Then their luggage receipts were confiscated. Les lost everything: luggage, money, watch, and ring.

From the perspective of the Department of National Defence, dealing with POWs was a straight forward affair, but internees were another matter altogether. Officially, Canada was to accord internees the same rights and protections as POWs, but in practice […] they were treated more like spies. Indeed, conditions faced by the internees were so bad that Canada would have been liable for prosecution under the terms of the Geneva Convention. After the indignity of his sea voyage, no one had to tell Les Gelb that German POWs had been better off. In reality most of the internees were refined and well-educated, many of the older ones being highly skilled professionals. Among their ranks were world class chefs, composers, musicians, scholars, engineers, doctors, artists, and rabbis.

Although Les doesn't recollect it, according to Erich Koch's book "Deemed Suspect" [12], the internees supposedly enjoyed a brief respite on the Plains of Abraham the next morning where they were fed Army rations, bacon, eggs, and bread with butter and jam. Having been cooped up on board the Ettrick, a view, any view, was a pleasant one. Later that day they had their first encounter with Canadian citizens. Some of the residents of Quebec City – men and women both – strolled around the exterior of the compound verbally insulting and spitting at them through the barbed wire. […] As it had been on the Isle of Man the internees were denied suitable work, distractions of any kind, contact with the outside world, news, or mail.

A key challenge in the early going was that while the POWs had been separated from the internees, there had been no separation of Nazis from anti-Nazis. To be sure, only those interned were in a position to know the difference. Certainly, the ritual observances of orthodox Jews served to identify them at least as being anti-Nazi. Camp "L" housed 90 Nazis and was only 60 % Jewish, but 89 % of the men there were refugees from Nazi oppression. […]

In the late summer and early fall, conditions in Camp "L" improved slightly. Fritz Lingen, who had been elected Camp Speaker, managed to obtain some sports equipment through his aunt and uncle. Slowly but surely Canadian authorities began to realize that most of the internees were not dangerous. The officers became less cautious and the guards less harsh. Les recalls that prior to the dissolution of Camp "L" the Commandant occasionally left his Packard [13] inside the camp to be washed.

In retrospect, some internees viewed their experience in a positive light while others considered it a dead period in their lives. The younger men tended to use the time to discover various aptitudes and talents whereas those who had already "found" themselves and their calling had a tougher time; the older intellectuals were hit the hardest, many of whom were hysterical and inconsolable. Someone coined the term "internitis" to describe the despondency, touchiness, self-absorption, and self-pity one experienced when faced with confinement. There were constant rumours, no news, no familial contact, no hope for release, no women, and no privacy. For his part Les was pre-occupied with just passing the time.

Segregation

[…] On 15 October 1940 Camp "L" […] was disbanded, the "Aryans" being shipped to Camp "A" (Farnham) the non-"Aryans" to Camp "N" (Sherbrooke). The 736 internees, including Les and Hans, bound for Sherbrooke were transported first by bus and then by railcars shrouded in barbed wire. While making the journey across Quebec, Les was struck by the vastness of space and the seemingly endless forests. They arrived at Camp "N" in the middle of a torrential rainstorm. This aged site, formerly a Quebec Central Railway maintenance facility consisting of two large sheds, six decrepit lavatories, and several train turntables, had been acquired by the Department of National Defence only two weeks prior to the arrival of the internees. Inside the steam-heated sheds there were mattresses, but no beds. A makeshift open-air "latrine" had been established which was no more than a length of large diameter pipe with a series of holes cut out of the top and placed on the ground at a slight angle to act as a sluice. Calculating the interior space of the two sheds there was a total of 29 square feet of space per internee, six square feet less than was mandated by British Ministry of Health standards.

In an effort to contain the tendency towards grievance that had characterized life in the camps up until that time, and to avoid a riot over the conditions at Camp "N", Commandant Major S. N. Griffin made a genuine, but ineffective, plea for co-operation. The internees protested by going on a hunger strike. Two days later Griffin committed to working with them in what he said was to be their home for some time to come, but still he failed to win them over. At this point a Major D. J. O'Donahoe stepped in to play "bad cop" to the Major's "good", using harsh language peppered with distinctively North American idioms like "no more monkey business". The internees, understanding his tone, but not his metaphors, failed to grasp his meaning. To close the deal he said: "If you play ball, I will play ball. If you won't play ball, I won't play ball." The perplexed European and predominantly non-English speaking group henceforth took to referring to O'Donahoe as Major "Balls". Another colourful guard at Camp "N" was Sergeant-Major MacIntosh, an anti-English Scot, who discharged his duties with such dictatorial bluster that whenever he issued an order the internees took to responding "yes, mein Führer".

Over the next four months both the internees and those who guarded them got on with the job of making Camp "N" as comfortable and functional as possible. Hans Kahle, who commanded the 11th International Brigade during the Spanish Civil War and who was commemorated by Hemingway in "For Whom the Bell Tolls", was elected Camp Speaker. Beds arrived. A camp school was established. Theatrical productions were mounted and musical concerts performed. Chores were scheduled providing the internees with a modest amount of "camp money" with which they could buy chocolate bars and the like from a tuck shop. The food improved dramatically owing to the fact that the gourmet chefs there took over the running of the two kitchens themselves, one of them kosher. Before long they were cooking for the camp staff and, on occasion, were even asked to prepare food for special functions in and around the town of Sherbrooke! Eventually mail service was provided, but no mail was permitted between camps. About two months into their stay at Camp "N", the internees were issued uniforms: blue denim jackets bearing a large red patch on the back and blue pants with a red stripe down each leg. The jackets offered little protection from the cold Quebec winter owing to poor construction; instead of stitching the lightweight red patch over top the heavy material, holes were cut out of the coats and the patches stitched in their place. Les was not so much demoralized by having to wear the uniform as he was angered by it's lack of utility.

Despite the large number of men in the camp, most internees associated with a handful of others based on similar interests and age. Les associated with no more than a dozen people. He befriended a young member of the German Rothschild family based on their mutual enthusiasm for motorcycles, and he also learned a good deal about optical equipment, particularly lens grinding, from a former employee of Leica. Owing to his youth, his mechanical mind, and his few associations, he avoided the internecine political disagreements between various factions (e.g. communist vs. anti-communist, capitalist vs. anti-capitalist) and he never personally witnessed any of the homosexual activity that existed.

Rectification Comes Slowly and in Stages

It wasn't until the fall of 1940 that the print media began publishing stories about the internment fiasco in Canada. […] Action had been slow in coming due to Britain's error of omission and Canada's complacency. […]

Britain was then willing to reclaim only 60 of the 2,290 internees she had sent to Canada, and was rather hoping that Canada and the United States would keep the majority of them. Many internees did wish to emigrate to the United States […], but because the British had originally classified them as "enemy aliens" most were precluded from remaining in Canada and all were barred from admission to America.

[…] On Christmas Day 1940 the first contingent of 236 internees including Lingen, […] and Kahle, returned to Britain aboard the Thysville. Three hundred and thirty more were shipped back on 17 June 1941.

Early in 1941 the Canadian government adopted new criteria for the domestic release of internees. Skilled and agricultural workers, along with some students, were among the first to be eligible. By April the Central Committee for Interned Refugees had found employment in Canada for over 250 men. […] On 13 May 1941 the Canadian cabinet agreed to individual releases for those with sponsors (immediate family in Canada). […] Those without sponsors or skills suited to the war effort had to wait for the status of internees to be changed from "POW Class 2" to "refugee", or for the responsibility of running the camps to be transferred from the Department of National Defence to the Department of State […].

By 25 September 1942 over six hundred internees had been released in Canada. On 11 November Camp "N" was dissolved and the status of all former internees was changed to "friendly alien", these men being granted temporary liberty in Canada. By December 1942 only 341 internees remained behind barbed wire, 113 of which were scheduled for return to England. Not until the halfway mark of 1943 was the final internee released.

On 10 December 1943 an Order in Council was passed confirming that the 952 former internees still living in Canada were eligible for naturalization after the war. They were not, however, eligible for combat […]. This was a bitter pill to have to swallow for internees seeking vengeance against the Nazi regime that had destroyed their lives. […]

Fortune Favours the Bold

The Gelb brothers effected their own release by reaching for the top. Although there was a thriving black market in the camps, news from the outside world was exceedingly difficult to obtain. Somehow Hans got his hands on a newspaper in which C. D. Howe was quoted as saying that the war effort in Canada was facing a shortage of skilled labour. Hans sent a letter to Howe explaining that he and his brother were capable engineers and Howe's office responded by asking about their area of expertise. Once their references were checked (the work they'd done in London for the War Department having clinched the deal) the two were released in July 1941 and sent to Toronto to work at Research Enterprises Limited (REL) in Leaside having been sponsored by none other than Canada's "Minister of Everything" [14]! Les and Hans were the first internees to be released from Camp "N", the entire camp complement envyingly seeing them off. And with that their 15 months in captivity was at an end.

Conscription

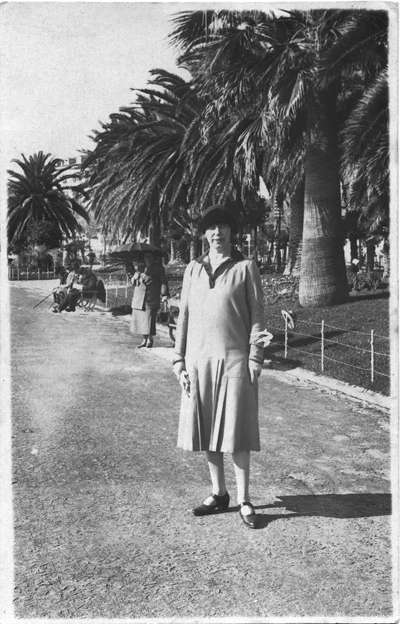

From day one the folks at Research Enterprises thought Les was an engineering genius. This is because his first assignment involved working with lens-grinding machinery. Despite having no hands-on experience, it was precisely this kind of equipment his ex-Leica employee friend in Camp "L" had familiarized him with. Despite knowing that Les was a former internee his colleagues treated him very well. The two brothers were to stay with the company for three years.

While his colleagues at REL treated the two brothers well, Les was surprised by the breadth of anti-Semitism in Canada. Overseas Les had encountered it only amongst the working class, but in Canada it emanated from the upper class. In 1942 while planning his first vacation in Canada, a skiing trip to the Laurentians, a travel agent explained that the destination was "restricted".

Les had applied for British citizenship in 1940 and it was finally granted in the autumn of 1944. The dispensation made him very proud and he cherished the certificate which stated "British subject presently in the service of the King" […]. However, this turn of events made Les eligible for conscription. In accordance with the National Resources Mobilization Act, all those conscripted into service were required to choose between "general" or "home" service, the former denoting willingness to see combat. To decline was seen as cowardly and those who did so were mocked by the term "zombie". Acceptance of general service was displayed on the uniform by a small black crest with the letters GS in red. Les's khaki uniform may no longer fit him, but the lower left arm of his jacket still bears that crest. He was sent to basic training, attached to the Corps of Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, and sent to Kingston for further instruction. Later he was posted to Camp Borden where he worked on tanks and other heavy equipment. By the time he left the Corps Les had risen to the rank of Sergeant.

Just prior to the end of the war Hans negotiated, on his brother's behalf, an extended leave from the army for "essential work" in the private sector. Hans had learned that the S. F. Bowser Company Ltd. in Hamilton was looking to design a diesel motor. In his application letter he claimed that both of them possessed the necessary engineering skill and experience. The truth was that Hans didn't, but Les was blessed with considerable ability in the area of "process" engineering. They were both hired to work at the firm's Toronto branch. Les was appointed Chief Engineer of the Experimental and Development Department and was granted a technical lease to begin the design. Not long after V-E Day [15] he was honourably discharged from the army.

Post-War Life

Soon after the end of the war Les got a job at Standard Machine & Tool Ltd. in Leaside, then the largest tool manufacturer in the North American auto industry. One of the most well-known projects he worked on was the Orenda jet engine under contract to A. V. Roe. For this Les was tasked with setting up a division within Standard and for hiring a staff of 30 to work under him.

The war may have been over, but Helen and Gustav were still in England and suffering terribly. During the blitz they had sought refuge in underground stations. During and after the war the brothers sent them a steady stream of food parcels which took seven weeks to get there when they got through at all. In the spring of 1945 Les filed an application with the Immigration Department for their admittance to Canada and was told that owing to the volume of similar requests, theirs would be processed in due course. Les consulted a Toronto lawyer he was friendly with named Rosenberg who told him that the only way to expedite the process was by means of a bribe and that the going rate was $ 500. The brothers hadn't the money so Les asked his employer for a loan. Just as it had been in Austria seven years earlier, approval was immediately forthcoming from the same clerk who at first had deferred the application.

When his parents arrived in 1946 the brothers could barely recognize their ailing father. Les worked hard to support them and, on occasion, his brother as well. Adding to their woes, housing was very scarce in Toronto and at first they could find no suitable lodgings. Once again associations through Les's motorcycling hobby were to provide a solution. Charles (Chuck) Stockey was Canada's dirt-track motorcycling champion when Les met him at REL during the war. Les had acquired a Triumph motorcycle and on weekends they would often tour together. Stockey's father, a wealthy English farmer, owned several homes in Toronto and Chuck offered Les and his family one on Woodlawn Avenue near Yonge Street. They lived there until 1949 when Gustav died of a heart attack at the age of 69. He was buried in a Jewish cemetery near Eglinton Avenue and Avenue Road. Helen moved to an apartment and lived to the age of 85. The elder Gelbs never had any interest in returning to live in Austria.

Hans married a girl in Toronto shortly after the end of the war and decided to strike out for California. He lived in Pacific Palisades and raised three children, but he had trouble finding regular work. Helen and Les visited him on a number of occasions and Les did what he could to help him, but he lost touch with his brother's family after Hans died in 1972 at the age of 60.

In 1954 Les met an Irish Catholic gal named Rita who had moved to Toronto from Guelph in search of a job. A mutual friend suggested she speak to Les who hired her as his personal secretary. They were married two years later. In 1962 they bought a house in Leaside very near to his workplace. Les chose the place because it had a two car garage and at the time he owned three cars and a motorcycle. Their only daughter, Barb, whom Les describes as "the perfect child", was born in 1958. They watched with pride as she attended Art College and went to work as an art director in the ad industry.

In 1955, XLO, the largest machinery company in Detroit, decided to set up shop in Canada and approached Les with an offer of employment. […] Les worked at XLO five years past the mandatory retirement age of 65. After two weeks of puttering around in his garden he was bored stiff and decided to return to the workforce. He made applications for two different part-time jobs and was offered and accepted both; one at Multi-Craft in Mississippi, the other at Volkswagen. He also took a third job working for Alfing, a German company that had made aircraft parts for the "Third Reich". Being courted and employed by Alfing was a strange experience indeed. A mild heart attack in 1996 encouraged him to retire for good.

In his private life Les pursued his hobby of acquiring and tinkering with various motor bikes and cars. He owned many different motorcycles – mostly English makes. He never once wore a helmet and only stopped riding bikes at age 61. One of his cars is a 1956 MGA which he bought as a wreck in 1957 and restored over an 18-month period. He's still driving it around Leaside today. Les also restored then sold a 1958 Buick convertible. For his workaday vehicles he bought a series of Cadillacs from a dealer friend.

Epilogue

Les's best friend in Vienna, the chap who along with his parents had seen him off at the airport in 1938, managed to escape Austria prior to the "Anschluss" and went on to study medicine. He fled to Palestine before the outbreak of war and joined the RAF [16]. After the war he opened his own practice in Stockholm. Les and Rita visited them several times and vice versa.

John Dunlop, the man whose father had saved Helen and Gustav, joined the British Army and served as an officer in a mechanized division. During Les's internment, Dunlop commanded a tank group that, due to his familiarity with the city in which he had spent much time as a youth, routed its German opponents in the battle of Antwerp. He won medals from the British and Belgian governments for his valour and he survived the war.

Les also kept in close contact with his parent's former cook, a woman he considered his second mother, right up until her passing in 2001. She survived the war as well as the peace that followed by hiding from the Russians during their occupation of Vienna. She married the Gelb's former chauffeur and together they operated a parking garage (street parking being prohibited) that Gustav had helped him acquire before the war. The couple even visited Les and Rita in Canada and Les remains in touch with their children and grandchildren.

When asked if he had known love before Rita, Les related the following tale. There was a girl named Marion that Les had dated in high school. The budding romance was interrupted by the "Anschluss". She, too, fled Vienna for England (in her case via a "Kindertransport", otherwise known as the Refugee Children Movement). At the outset of war she and Les reconnected in London, picked up where they left off, and planned to marry before fate once again intervened. While Les and Hans were interned Marion's family moved to Detroit and before the brothers were released she married another. They (Marion and Les) nevertheless remained friends for life!

Reflections

At the venerable age of 92, Les Gelb considers himself a remarkably lucky man. He has lived a full and happy life in Canada, a country he never imagined would become his home. He is grateful that his parents saved him from the Nazis, and he is thankful for his brother's efforts in England, in the camps, and during the war. The two brothers made an excellent team; Hans created the opportunities and Les made them work. He feels fortunate that after the war he never once had to look for work or write a resume, at least until he retired the first time. And he's deeply grateful for the support of his loving wife and his adoring daughter.

There are, however, a few things that he will never forget and can never forgive. His deepest wrath is reserved for the Austrian people who turned on Jews in their own country more viciously than did the Germans in theirs. Despite his love for his home country and his fond childhood reminiscences of it he never considered moving back there for this reason, although he did often return to holiday and visit friends. He understands and accepts that he and others were "deemed suspect" before and during the war, but he remains disappointed with Churchill and the British government for their disingenuous handling of the matter.

Leslie Gelb died in August 2009.

[1] Passover or Pessach: important Jewish holiday, commemorating the Israelites' exodus from Egypt.

[2] Hebrew for "Sons of the Covenant", international Jewish service and welfare organisation.

[3] "Subhumans".

[4] These peace treaties after WW I officially ended the state of war between Germany/Austria and the Allied Powers.

[5] Nazi Germany's anti-Semitic Nuremberg Laws (Nürnberger Gesetze) of 1935 defined, among other things, who was Jewish, deprived Jews of German citizenship and prohibited marriage or sexual intercourse between Jews and non-Jewish Germans.

[6] National airline of Belgium (today: Brussels Airlines).

[7] Croydon Airport was the main airport in London in those days.

[8] With the outbreak of WW II, German and former Austrian, later also Italian citizens were declared "enemy aliens" and put in special internment camps. See also chapter "Collar the Lot".

[9] Quotation by Winston Churchill, regarding "enemy aliens".

[10] The "Anschluss" refers to the annexation of Austria and its integration into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

[11] After the sinking of the Arandora Star, which was followed by vigorous protests and a change of public opinion, British authorities gradually relaxed their harsh internment policy.

[12] Erich Koch, Deemed Suspect: a Wartime Blunder, Toronto 1980; an autobiography by a German Jew, who also was deported to a Canadian internment camp.

[13] Automobile marque by the then Packard Motor Car Company in Detroit, USA.

[14] Nicknamed the "Minister of Everything", C. D. Howe was a powerful Canadian Cabinet minister for the Liberal Party for 22 years.

[15] "Victory in Europe Day", commemorates 8 May 1945, the end of WW II.

[16] Royal Air Force.