Karl Fox

This is my life

Karl Fox was born in 1925 in Vienna. After the "Anschluss" – the annexation of Austria and its integration into the German Reich on March 13, 1938 – he had to leave his school and attended a Jewish school in Stumpergasse, which was far away from the 15th district, where he was living.

By early 1939, most Jews had been disowned of their possessions and property. We left in June 1939, luckily my brother Richard, who was already in Brussels since early 1938, arranged an illegal entry for us. Our mother had left Vienna for London on a domestic permit, arranged by another brother, Rudolf, who had lived in London since early 1938. We hoped that once our mother got there she would be able to apply for permits for all of us to join her in London. However, time ran out and she got stranded in England and we in Brussels. Soon after, in September 1939, the war broke out, at which time all communication ceased.

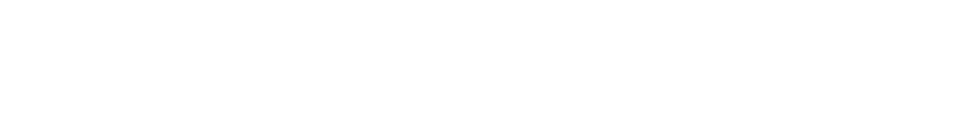

In June 1939, prior to leaving Vienna, we stayed the last few days with our aunt Berta Teweles. She and her two sons remained in Vienna and the only time we had news from them was a postcard, which we received in Brussels before the war started. What happened to them or where they finished off can only be assumed due to the circumstances that were prevailing at the time. They were deported to some extermination camp like all the others who stayed behind.

Our departure from Vienna started from Westbahnhof (the western railway station). My father, sister Edith, younger sister Margit and I shared our dangerous journey with a family friend by the name of Leo Fischer and Hans Diskant, an industrial chemist who was the son of a friend of my brother Richard. In all, there were six of us who undertook the uncertain journey to Belgium. We travelled by train as far as Cologne, where we stayed at a designated hotel, all arranged for us by the guide who met us at the station. On arrival in Cologne he guided us to the hotel, leaving us with strict instructions to stay indoors and avoid being seen. The only ones who sneaked out from the hotel when we needed food were my younger sister and I; being young we aroused less attention.

After a few days of staying in that hotel, the guide came and told us to take our belongings and follow him, at a distance, to the railway station. On arrival at the station he indicated with a gesture by holding his hand on his chest pointing towards a compartment, indicating for us to board the train. Our next destination was Aachen. There again the guide walked a fair distance ahead of us, then boarding a tram, which we boarded as well, this took us to the outskirts of Aachen. We stayed overnight at a retired farmers place, the following day we were picked up by the same guide, instructing us once again to follow him. After a long march we got closer to the Belgian border, always a fair distance behind the guide, just so that we would not lose site of him. This was in case we got arrested he would have time to get away without being caught. By the time we almost reached the border it was getting dark and it had started to rain. At this point we were led off the road and were directed into the fields, walking in mud and between cattle off and on. We kept on walking for a long time, getting wet and very muddy, by that time the guide kept very close to us. He remarked that the rain was very good, because there would be fewer guards on the look out. We reached a hedge that we had to crawl underneath, landing in a ditch that was full of water next to a country road. At this point our guide said to us to stay low while he went onto the road to put his ear to the ground to listen for the approach of an anticipated vehicle. He repeated this exercise several times, until he heard the noise of a car approaching, which was supposed to come and drive us the rest of the way to Brussels. When it finally arrived we all boarded the car, except our guide. Later on we found out that the place where the car had picked us up was called Herbesthal, which was already on Belgian soil.

We arrived in Brussels in the early hours of the morning on Rue Royal, opposite Rue Godefroid de Bouillon. The driver of the car said to us to walk down the street to house number 4, our brothers Richard and Gustav were waiting there with their wives and nephew Freddy.

Karl and his sister Margit went to school in Brussels for approximately a year and a half. The Belgian authorities were very kind, so Karl's father hoped to gain entry permits into England, becoming more and more desperate as the situation in Europe worsened.

When in May 1940, the Germans invaded Belgium, the whole country was thrown into confusion and chaos [and] a big exodus started towards the west. The British Expeditionary Army [1] was coming up from France heading towards the coast.

My father, sister Edith, younger sister Margit and I, like so many others, joined the British Army on their retreat, moving towards the coast by transport of various means, mainly on foot. We were hoping that once we reached the seashore the British would take us across the channel with them to England to be united with our mother. On our way towards the coast the endless line of British soldiers and civilians was attacked by German dive bombers (Stukas) on many occasions. When these attacks occurred we threw our belongings in the ditches and ran into the fields. When the attack was over, we collected our belongings and continued on our march towards the coast.

On our way we passed through various towns with almost all shops abandoned and left open for anyone to help themselves to goods just so that they did not fall into the hands of the advancing Germans. Grocers poured lard, dried fruit, etc. into the gutter, where it all mixed up into a big mess, looking so unreal and chaotic.

When we went through Ypres we were accommodated on an abandoned chicken farm inside an incubator shed. The whole place was in a terrible mess with rotting eggs everywhere. The reason why I mention this particular incident is because the people of Ypres had already suffered terribly at the hands of the Germans during the First World War. To them, hearing us speaking German made them think that we were German spies. Some of the local men came and grabbed us and marched us off to the town hall. On the way to the town hall one of the men from the crowd tried to hit my father with his fist, luckily he reached across over my shoulder so that he only hit my father's hat off. When we reached the town hall we were handed over to the Belgian Army. Once inside we tried to explain to them that we were Jews trying to get away from the Germans, luckily there was a Jewish officer present who understood the irony of the whole situation. He then took charge of the procedure, telling us that we had to wait until nightfall. We asked him why, so he took us to the balcony and said, "See that mob down there waiting? One could not explain to them this situation in the mood they are in", so later on in the evening we were released at nightfall; by then the crowd had dissipated. We then continued on our way heading closer to the coast, joining up again with the British Army.

Most of the time we marched with the British Army. During our first day with them, the British blew up most bridges in order to slow down the advancing Germans. On our march with the British troops we were always welcome to join in at mealtimes. They set two rows of bricks on the ground and placed some steel plates on top, then turned a flamethrower on underneath and, in no time at all, we had some hamburgers.

When we finally neared the coast we realized that we could not stay with them. They headed towards Dunkirk, only later on did we find out how bad their evacuation across the British Channel turned out to be, with the German dive bombers attacking them all the way across. (In 1944, the British Army and their Allies returned across the Channel, beginning their victorious invasion and starting to defeat the German Fascists, thus liberating Europe from Nazi enslavement. [2]

When in May 1940, the Germans invaded Belgium, the whole country was thrown into confusion and chaos [and] a big exodus started towards the west. The British Expeditionary Army1 was coming up from France heading towards the coast.

My father, sister Edith, younger sister Margit and I, like so many others, joined the British Army on their retreat, moving towards the coast by transport of various means, mainly on foot. We were hoping that once we reached the seashore the British would take us across the channel with them to England to be united with our mother. On our way towards the coast the endless line of British soldiers and civilians was attacked by German dive bombers (Stukas) on many occasions. When these attacks occurred we threw our belongings in the ditches and ran into the fields. When the attack was over, we collected our belongings and continued on our march towards the coast.

On our way we passed through various towns with almost all shops abandoned and left open for anyone to help themselves to goods just so that they did not fall into the hands of the advancing Germans. Grocers poured lard, dried fruit, etc. into the gutter, where it all mixed up into a big mess, looking so unreal and chaotic.

When we went through Ypres we were accommodated on an abandoned chicken farm inside an incubator shed. The whole place was in a terrible mess with rotting eggs everywhere. The reason why I mention this particular incident is because the people of Ypres had already suffered terribly at the hands of the Germans during the First World War. To them, hearing us speaking German made them think that we were German spies. Some of the local men came and grabbed us and marched us off to the town hall. On the way to the town hall one of the men from the crowd tried to hit my father with his fist, luckily he reached across over my shoulder so that he only hit my father's hat off. When we reached the town hall we were handed over to the Belgian Army. Once inside we tried to explain to them that we were Jews trying to get away from the Germans, luckily there was a Jewish officer present who understood the irony of the whole situation. He then took charge of the procedure, telling us that we had to wait until nightfall. We asked him why, so he took us to the balcony and said, "See that mob down there waiting? One could not explain to them this situation in the mood they are in", so later on in the evening we were released at nightfall; by then the crowd had dissipated. We then continued on our way heading closer to the coast, joining up again with the British Army.

Most of the time we marched with the British Army. During our first day with them, the British blew up most bridges in order to slow down the advancing Germans. On our march with the British troops we were always welcome to join in at mealtimes. They set two rows of bricks on the ground and placed some steel plates on top, then turned a flamethrower on underneath and, in no time at all, we had some hamburgers.

When we finally neared the coast we realized that we could not stay with them. They headed towards Dunkirk, only later on did we find out how bad their evacuation across the British Channel turned out to be, with the German dive bombers attacking them all the way across. (In 1944, the British Army and their Allies returned across the Channel, beginning their victorious invasion and starting to defeat the German Fascists, thus liberating Europe from Nazi enslavement.2After parting company with the British Army we continued walking towards Ostende where we found accommodation in a closed down and empty school. The air raids were intensifying and we spent a lot of time in the shelters. Each time we came out of the shelter more and more houses were destroyed by the bombs, only hitting civilian targets. At that point we did not know which direction to go. We boarded a tram that was abandoned with a lot of other people, like all other services that had come to a complete standstill due to the chaos caused by the war. One man among the people we travelled with was an engineer who managed to operate the tram. The tram ran along the coastline bringing us to Knockke, not far from the Dutch border. In normal times this was a popular seaside resort. All services had stopped in Knockke, like in all other places. Once again we were housed in a school sleeping on the floor, at least a roof over our heads.

The following day the Germans arrived with their weaponry. We were returned to Brussels, uniting with our family once more. Back in Brussels we returned to school, that is my sister Margit and I. [

] The Nazis established their Gestapo headquarters in Avenue Luise in Brussels, our lives were again filled with anxiety and fear for our future.

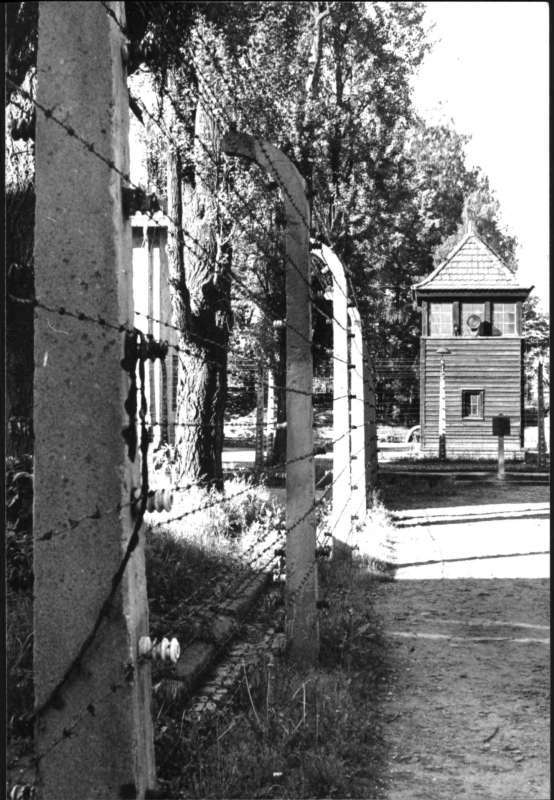

On 16th October 1942, in the morning, two Gestapo men arrested Karl, his father and sister Edith, his younger sister Margit had already left for work that day. They were taken by truck to the transit camp Malines (Mechelen) in Belgium, from there on the 24th October 1942 to Birkenau, the extermination camp near Auschwitz.

When we finally arrived, we could not believe what we came face to face with, to depict the enormousness of barbarity that greeted us on arrival is impossible to explain and even more impossible to understand for anyone who did not witness these horrible sights, our brains could not cope with the situation that our eyes perceived. The train had slowed down to a walking pace and moved to the end of the ramp. It was late afternoon on the 26th of October 1942, we saw columns of prisoners in striped uniforms march past our train heading towards the entrance of the camp coming back from work, this was our first impression of what is awaiting us. These prisoners looked extremely tired, emaciated and sad with vacant expressions on their faces, at the rear of the column they were dragging a few dead prisoners (Häftlinge) beaten to death at work, at the entrance of the camp a band was playing as they marched into the camp – utterly incongruous.

As soon as our train had stopped we were shouted at "raus, raus" (out, out), so we had to descend in a hurry, dragging our few belongings quickly off the train. We were bewildered as everything went so fast from that moment on, plus the impact of what we saw as we arrived, we were shouted at to leave our luggage on the side and march up single file to the SS officer in front, who did not speak, and as each person came up to him he only indicated with his thumb to the left or right: my sister Edith had to go with the women and children were she must have experienced the same treatment. My father was with me until we got to the point of being sorted to the left and right, there he had to go to the other side, where, I found out later, they went direct to the gas chambers.

We were then marched off into the camp of Birkenau. What happened during those first few hours is very hard to relate in human terms, everything that was done to us and what we witnessed was impossible for our brains to absorb, the horrible conditions we were suddenly faced with, we were neither told nor asked, everything was just done to us, we had to undress then were shaven from top to bottom and each were tattooed a number on our left arm. Next we were marched off to a Block, this was the name of the barracks we were housed in, usually there were three tiered bunks on either side all along the length of the whole Block. We had to climb into these bunks and wait for things to follow, a small inmate in jackboots was in charge of this Block. A young fellow from our transport wanted to know where he could relieve himself and came down from his bunk to ask the Kapo [3] for directions, a normal request. The Kapo asked him to come closer and as soon as he stood in front of him the Kapo kicked him very hard in the groin so that the fellow fell to the ground rolling with pain, from that moment on no one dared to ask for anything, we knew then that this was the beginning of the abyss of human suffering and total degradation.

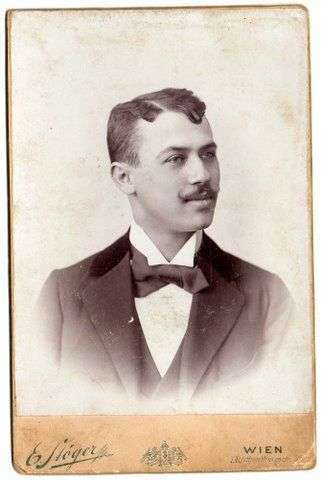

We remained that night in Birkenau, very early the following morning we were called outside to assembly on the side of the Block, then out of the whole group 200 men were selected, I was among them, shortly after we were marched off to Auschwitz into the main camp, through the "Arbeit macht frei" (work sets you free) gate. There we were dipped, completely submerged in a stinging solution of disinfectant, which left our ears, eyes and other parts sore for quite some time, we had no food nor drink up to that point, with all what happened to us our senses were so numbed that we did not think of food, only what was going to happen to us next. After a short while at Auschwitz we were marched off to Jawischowitz, a coalmining concentration camp 14 km from the main camp Auschwitz. [4] At the time of marching off we did not know where we were being taken, nor that this was our chance for survival, because they needed more workers for the mines. At Birkenau where we arrived, even if one did not go immediately to the gas chamber and made it into the camp, the average one could last there, with the treatment dished out, was three months, before ending up in the gas chamber.

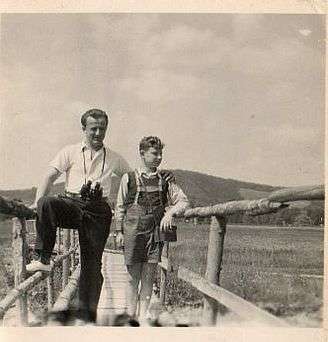

On arrival at Jawischowitz Karl met Lutschi Weinber, a young man from Vienna, whom he had got to know in Brussels.

To meet up with Lutschi was my second big chance for survival, he gave me advice and looked after me from then on as well as circumstances permitted. At first I could not take the hard work in the coalmine, I had just turned 17 years, with the inadequate nourishment, poor clothing and the first winter approaching, marching three km to and from the mine, in the mine standing in water, then coming out of the mine marching back to the camp in wet shoes and trousers freezing to ice on the way, I just could not take it and wanted to give up, and told my good friend Lutschi that I do not want to eat because I can not endure this agony much longer. My back was so painful that I could not sleep on it, I slept with my face down, the meagre food we got there I refused to eat, as I was getting so despondent, Lutschi slapped me across my face and said to me, "You eat now, you hear, you will get used to it and we all come out of here together, alive!"

Later on I realized how this helped me to keep on going and gave me inner strength and hope, which at that time in our situation meant everything in order to stay alive and not give up. Later on Lutschi helped me to get a job at the Schreibstube (the camp office). I was a messenger and had to take messages to the various Blocks and sickbay back and forward, all day on the run, however, this job provided me with extra soup and was a lot easier than working in the mines; unfortunately this job was too good to last very long. The Lagerführer [5] was displeased with a report that I was supposed to bring to him, he said I was late in delivering it, he gave me a few punches and ordered me back into the mines.

The camp at Jawischowitz had approximately 2,000 inmates, we worked in two different coalmines, also we worked above ground, which was called Schachtkommando, there we mainly had to dig trenches for pipe laying and pouring concrete foundations for electrical plants around the coalmines. On occasions the Lagerführer would turn up, at random, to observe us march to or from work, at times he would decide that we did not march well enough. As punishment we had to do sport, immediately upon arrival back in camp from work, sport consisted of running back and forward on the Appellplatz (roll call area) with shouting commands from the Kapo, down, up, forward, back, sometimes in mud or snow and all this after work, tired, hungry and black with coal dust, if we were lucky it only lasted half an hour, quite often longer, depending on the mood of the Kapo, and of course if the Lagerführer was present he decided when to stop the sport.

Other times random body searches were carried out as we arrived back in camp from work, if a morsel of food or a cigarette was found on a person he was taken to the office, where he received 25 lashes across his back side, or less if he revealed the source where he received it from. In the mines we worked alongside Polish civilians, they were directed and ordered by the German authorities to work in the mines for the war effort but they were not imprisoned. For a short while, I was lucky in meeting a student from Krakow, he also was ordered to work in the mines as a civilian, for some time he gave me some food, he always waited until I had eaten it all up, for fear of being punished if found on me by the camp authorities if a search was made upon returning to the camp.

Every two to three months, an SS doctor came from the main camp Auschwitz for selection, he sat behind a table in the dining hall and everyone had to march up to him, naked single file, he would just point his finger left or right, to sort out the ones who were too emaciated and no longer of any use, usually 200-300 men, they were then sent off in trucks to the gas chambers, within a few days an equal amount of men arrived from Birkenau as replacement, the same way as we had, sorted out from a recent arrived transport, therewith they escaped from immediately going into the gas chamber. On one of these selections our friends Hans Neumann and Sigi Gutmann, both from Vienna, were selected, they were fully aware what it meant, neither had any strength left and they were totally emaciated, they were of an age where resilience under such conditions was no longer possible.

In Jawischowitz Karl met nearly 20 men from Vienna, among them Ludwig (Lutschi) Weinber and Kurt Herzog, who lives in Sydney now and is a good friend of Karl.

Sadism was part of our routine treatment as well. Abraham Katz came from Krakow, I used to work alongside him for a while in the Schachtkommando, digging trenches, one day he escaped from the camp during an air raid, while all lights and the electrified wire were turned off, he managed to get as far as 30 km away from the camp before he was caught, the SS traced him through the various farmers, who gave him away by letting the SS bloodhounds know where some food or clothes were missing. When Katz was brought back to the camp, he was very weak and exhausted, the Lagerführer ordered that he be put in solitary confinement and fed for a few days, then in front of assembly he was hung, at the same time the Lagerführer was telling us that this is what will happen to anyone attempting to escape. Katz shouted to us all, before they put the noose around his neck, "Kopf hoch" (heads high), he was only 19 years of age.

The incidents of cruelty were a daily ongoing treatment handed out to us, the barbaric inhuman behaviour of the SS guards, plus beatings from our superiors in the camp, was of the most brutal kind, at no time did they have to give an explanation or account of their actions; they could perpetrate all the sadistic cruelty they wanted with impunity. On one occasion, as our shift in the coalmine had finished, I had an attack of diarrhoea and had to run to the pits latrines after work, resulting in coming late to assembly before taking the lift up (the Kapo had to count us before we went up to the surface). The Kapo had counted and one man was missing, me, as I arrived at the lift shaft he was waiting for me with a large piece of timber in his hand with which he hit me across my head, I was lucky that I absorbed most of the blow on my arm, also the punishment would have been much more severe, had he reported me to the authorities upon returning to the camp.

After six months of working in the coalmine I developed appendicitis, the operation was performed by Dr. Stefan who was an aryan Pole and not fully qualified as a doctor. The Jewish doctors under his charge guided him while he operated on me, this was the usual procedure whenever he operated on anyone else. The anaesthetic was crude, just a small mask over my nose and mouth with a good dose of ether sprayed over it until it knocked me out. I went back to work in the mine three days after the operation, fearing being sent off to the gas chamber if I took longer to get well for work.

Lutschi Weinber had some influence at the camp office where he was befriended with the Schreiber (bookkeeper) Karl Gruemmer. He managed to get me the job back at the office, due to the Schreiber putting in a good word with the Lagerführer, telling him that I was needed and efficient at my job. On another occasion the Lagerführer came into the camp drunk, riding on his motorbike, to be looked at by the mechanic, Leo Schnog, a Dutch Jew, who was the Bademeister (bathhouse master) looking after the boilers and doubling up as the mechanic. As I was nearby, I tried to assist the Lagerführer to steady the bike as he was losing his balance and the bike fell over, he hit me in the face and again I had to go back to the mine. It needs mentioning, had I not assisted him my punishment would have been much more severe.

In the coalmines when each shift ended we all had to assemble in the lift shaft area, we sometimes had a little spare time before all the inmates from our shift converged to be counted and taken up to the surface of the mine, we used these precious moments to lie down against the warm steam pipes covered with lagging, to rest our tired bodies and to doze a few minutes, until the Kapo shouted at us to assemble to be counted before we ascended. Another occasional meeting place was at Leo Schnogs, whenever time permitted it, we met in the boiler house. While he stoked the boilers for the showers, we could warm ourselves and talk for a while there. [

]

When Mussolini pulled out of the Axis in 1943, the Germans then occupied Italy and shortly after the Italian Jews started arriving in Auschwitz. [6] Out of these transports we received some men in the usual replacement order, unfortunately these were all business men, bankers and mainly skilled professional people, therefore not used to this hard slave driving work plus the bad treatment etc. In the late Primo Levi's [7] words, it was an advantage to speak and understand German, which they did not, to understand a command immediately and react to it saved you from beatings and in many instances ones life, because if you were beaten up and you got injured to the point that you could not work, you were ready for the ovens. With all those disadvantages most Italian Jews did not last very long. Out of the transports of the Greek Jews who arrived in Jawischowitz as replacements in the usual process, some of these men were manual tradespeople and could do the hard work, although suffering under the cruel conditions, and again the lack of understanding German was a big disadvantage. These Greek Jews came from Saloniki [8] and amongst them was a surgeon by the name of Cuenco, he got a job in the camp hospital and turned out to be a godsend, he was so highly skilled and operated on people with instruments he fashioned himself, or had them made up in one of the workshops in the camp. The injured men he sewed up would have been sent to the gas chambers, had it not been for him. I watched some of the operations, and one I remember quite clearly, a young fellow was brought back from the mine with half his face torn open by a big piece of coal which fell in his face. Dr. Cuenco stitched his eye back into the eye socket and by the time he finished the whole operation he had stitched right across his face and the forehead, with such an injury he would have definitely finished in the gas chamber had it not been for this marvellous doctor. I met the fellow after the liberation in Brussels at a special gathering. He commented how lucky he was at the time. Dr. Cuenco survived and became a well-known surgeon after the war.

My friend Lutschi had an extra job on the side after returning from the mine, he was called the Scheisshausdirektor (the latrine director), for this he got a second helping of soup. His job consisted of taking the horse cart from the main gates and guiding them to the latrines where he had to pump the excrement into the tank and return the cart back to the main gates where the guard handed the reins over to the civilian who took the cart away. On occasions, specially during the winter months, when it was bitterly cold, we went to the Trockenkammer (drying room) which was run and operated by our friend Max Folkmann, who got this easy job because he was a professional magician and used to entertain the SS at their quarters; he also received extra food and cigarettes. Max was then 45 years of age and, had he not been able to use his professional skills, he would not have lasted more than three months in the mines. Max survived the camps and went back to Vienna to resume his professional career; he died a few years later in Vienna. Some other friends I was together with in the camps went back to Vienna to continue their lives there, especially the ones who returned to their professional or political careers. The inmates who were lucky enough to land an extra job on the side in the camps, like Stubendienst (cleaning the barrack), hair cutting and shaving of the inmates etc., would get extra soup or a piece of bread, depending on the amount of work done and the decision of the superiors whim. Max Margules was a sign writer by trade, he had a permanent job of writing the numbers on our striped tunics, for that he got extra food, but he still had to work in the mine. [

]

The dental treatment in the camp was not only primitive but almost non-existent. I had four teeth which needed filling, the pain got unbearable so I went to the Revier [9]. The only thing they could do for me was extract the lot, I had no choice. In order to get rid of the pain, the four teeth had to be extracted on the spot, there was no injections and the pliers they used were for front teeth only and my teeth which had to come out were all back teeth, one or two of the teeth broke off, because they could not get a good enough grip with the wrong pliers, the dentist fumbled around in my mouth to find the pieces of roots, by the time he had everything extracted there was blood everywhere, two fellows had to hold me down, because I was not able to take any more of the torture, the next day back to the mine.

A young German Jew of the same age as I was, by the name of Kurt Hirschfeld, worked in the same Schicht (shift) as I. His job was to shovel the stones that fell off back onto the conveyor belt but he was not a very strong person and new in the mines so he could not keep up with the amount of stones that fell off. When the overseer came past he gave him a beating for not being able to shovel fast enough, he was in tears, on many occasions I helped Hirschfeld out and shovelled some of the stones back onto the conveyor belt for him. I was very tired myself but could not look on to see him get beaten up. [

]

During the winter months a frequent plague was frostbite, due to the poor footwear, inadequate clothing and lack of proper nourishment, our circulation in the subzero winter climate was at its lowest. I also had a bout of frostbite on my toes, with cracked toes and blood oozing out. I had to go to the mines, due to my young age it all healed again, otherwise gangrene would have set in which would have been the end of me. An electronic engineer by the name of Fuchsenbrenner, a Jew from Krakow, was in charge of the electrical workshop, among other jobs he used to repair the radios for the SS quarters, giving him access to the kind of material used for radios, and towards the time of the Russian offensive he assembled a small receiver to enable us to listen to some news. We shared this clandestine and risky undertaking with a few aryan political inmates, who, for their convictions, had already been incarcerated since 1933. On some occasions I was also listening, sometimes I had to be on the lookout when they were listening and had to tap on the basement window in case an SS guard came into the camp, to give Fuchsenbrenner sufficient time to quickly dismantle the receiver, this was extremely dangerous but a chance to get some news from the outside world and with it hope! I remember one news item coming through when General von Paulus [10] spoke from Russia, where he was a prisoner of war, he was appealing to the German Army to throw down their arms and stop spilling more blood, because the war was lost he said. [

]

When the offensive from the east began and the Russian Army came within 60 km from Auschwitz, the mass evacuation began, in the way of a forced march. First the able inmates of Auschwitz and surrounding camps marched past our camp, our camp joined on behind on the 18th January 1945. The infirm who stayed behind in the sickbay, we feared, would be finished off, each with a bullet in their head. However, the Russians advanced so fast and, with the hurried evacuation going on, the SS did not have time to attend to this usual and final act, with the result that these inmates were falling alive into the hands of their liberators. All this I found out later when I was back in Brussels, from our comrade David Otto, who broke his leg just before we were marched off, and he had to stay behind in the camp hospital. When the Russians liberated them and he got well he was returned to Brussels via Odessa. Before we were marched out of the camp we were told that we are going to a new camp, but not where or how far, just somewhere in Germany. The first night we had to march through till the early hours of the next day, the Germans were always driving us on to march faster, we were pushing cartloads of the belongings of the SS. The ones who could not keep up and collapsed with exhaustion due to their physical condition were left in the ditch with a shot in the neck, no prisoner was supposed to fall alive into the hands of their enemy, an order issued by Himmler, to prevent us from telling what happened. We got a few hours of rest during the early morning hours after marching the night through, only because the SS guards were in need of rest themselves. The ones who had still a blanket were lucky, for it meant resting out in the open in the bitter cold and on top of the snow.

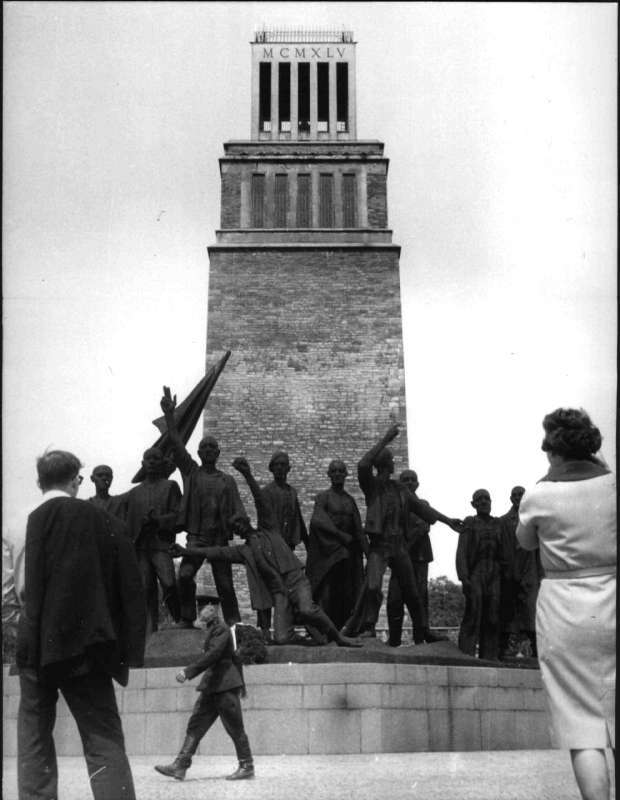

After three days of marching, the prisoners were chased into a train with open cattle wagons, 80-100 per wagon. They passed Gross-Rosen, another concentration camp which was already full with prisoners, and so they were brought to Buchenwald concentration camp.

The journey continued until the next dawn, when we arrived at Buchenwald. There we had to remain in the wagons until they were ready to process our transport. Then we were chased out of the wagons, assembled, counted, then marched into the camp. Many remained in the wagons frozen and no longer alive.

In Buchenwald we were put through the same treatment that we were subjected to when we first arrived in Auschwitz, over two years earlier, name taking, new number (117,405), disinfection dip etc. and, at long last, a little warm soup and bread for our frozen and starved bodies, after that torturous transportation. What struck us immediately after arriving in Buchenwald was the high standard of morale amongst the aryan inmates, they were mostly long serving political prisoners and the internal camp administration was mainly run by these prisoners, most of whom had been incarcerated since as early as 1933, right after Hitler came to power in Germany. As much as it was in the power of those political prisoners, they kept exceptionally good order in this camp, unlike Auschwitz, the Kapos and superiors did not ill-treat fellow prisoners too badly.

Shortly after their arrival Karl and his comrades were taken 70 km from Buchenwald, to an outlying work commando, where they had to work in a quarry. Then they were housed in bunkers in the Thueringen woods, where they had to load trucks with ammunition that was stored in the forest, which was very difficult work because of the snow and the bad condition of their shoes. Next they had to lay railway tracks outside of the Thueringen woods, near Krahwinkel, where the men had to sleep in tents despite the snow.

On our march back from work, our comrade Ernst Kandler stepped out of the line, because someone behind him had caught his heel, and so his shoe came off his foot. He only wanted to put his shoe back on again but the SS guard who marched alongside the column opened fire and shot him through the heart, with the excuse that Ernst tried to escape. Less than two weeks before our liberation, our quiet comrade from Vienna had been murdered. Our lives were totally expendable; without explanation they could dispose of us at will at any time.

The situation became increasingly more disorganized, the dead bodies could no longer be transported back by lorry to Buchenwald for burning. A few inmates were selected, of which my good friend Lutschi, his brother Kurt, and I plus a few other comrades formed a group. We were marched off with spades and axes up a hill across from our tent camp, where we had to dig a large hole across which we had to lay some rail tracks and then fell some trees which were placed under the tracks and set alight. Then the emaciated and mutilated dead bodies of our comrades were thrown on top of the tracks to be incinerated. Overhead Allied planes were flying very high, the SS guard sitting next to us with his submachine gun lying across his lap, and looking up he remarked and laughed, "Ja, einmal muss jeder sterben" (everybody's got to die one day). During a tunnel excavation, Max Salzmann, a stage performer from Berlin, another old friend of ours, was buried alive under a collapsed part of the tunnel, due to lack of safety precautions, since no care was taken for our safety and, according to the Nazis, Jews were only Untermenschen, sub-humans. As so often during those horrible agonising times, another dear friend perished in the most unspeakable agony.

In the last three months of our time in the camps, Lutschi, who never gave a sign of giving up hope, came to me for the first time, with the doubting statement about our chances of survival. By then we were dragged around so much and the treatment was getting worse with every day, he feared, as we all did by then, that the Nazis may decide at any moment to finish us all off, it was merely a question of when will the order come from their superiors for this final act. This thought became our constant companion on the march back to Buchenwald, which began about the 3rd April 1945.

On the march back, there were many Allied air raids, the towns the prisoners marched through went up in smoke and they had to spend the nights in the open fields.

As we were approaching Weimar (where Goethe used to reside) and nearing the foot hills of Buchenwald, our comrade Max Margules came to me and asked me to help our comrade Pauli Treitler by supporting him under his arm on one side, and Max on the other, since Pauli had reached the stage of weakness were he could barely walk straight. I said to Max that I have no strength left to keep myself on my feet, to which Max replied that we have to try to help Pauli pull through, so I put my arm under his. Pauli was asking in a semi-conscious state, "Wasser, Wasser" (water, water). As the column came to a temporary halt, which often was the case, I slipped down in the ditch, and in a rusty conserve tin I had attached to my belt with a piece of wire, I got him a little muddy water to moisten his lips. The danger of getting shot for this was very real, but I took the chance. Sadly, just as we entered Weimar, Pauli collapsed completely. The guards ordered four inmates to carry him until we were outside of Weimar, beginning the ascent up to Buchenwald. There Pauli was put down in the ditch and left with a bullet in his neck, just under a week before our liberation, after suffering for so long and surviving to this point, he was murdered – finished off in such a horrible atrocious way.

The last few days in Buchenwald, before the liberation, were getting absolutely chaotic, with all the outlying camps being brought back from various directions, Buchenwald was overflowing with inmates. My dear friend Lutschi remarked again that if we are not liberated soon, they, meaning the Nazis, will finish us all off. By then the situation was absolutely impossible to describe, dead bodies everywhere, filth, hunger, no room to be housed, not having had a wash or shower for months, no sign of any food coming, and covered with lice. We were among the last few columns to arrive back in Buchenwald. By that time, the Blocks in the camp were overflowing with inmates, so we were housed in the adjoining machine sheds, sleeping on top and under work benches and machines, wherever one could find some space. Every morning we pulled some dead comrades, who had died during the night, from under the benches and piled them on a heap outside the shed, there was no more time to collect the dead and take them for burning to the crematory. Everything was getting more and more out of routine and disorganized. At last a little watery soup was brought down from the main part of the camp to be distributed in front of the various machine sheds. Only the ones who still had the strength to queue up and fight for a position got a little cold soup, there was never enough for all who stood in the line – the little we got we shared among the closer comrades.

Lutschi was 36 years of age and I could see his energy was draining out of him very fast towards the last stage of our suffering, at his age under those terrible and unspeakable conditions a body did not have the resilience to keep going physically. He had to fight much harder than a younger person, but he never complained nor did he ever show a sign of giving up; he was always a hero in my eyes. Throughout our time together in the concentration camps, I always admired and benefited from his astute ability of assessing situations ahead, which was of invaluable help under the terrible conditions and constant danger we had to live. Not a practizing Jew, he never did any wrongs to his fellow Jews, correct and dependable, to this day I think of it as a miracle that we managed to stay together and survive together, an unforgettable friend, and as always, I cherish his memory.

On the 9th April we were chased out of the sheds and marched to the barrack section up to the main camp, not knowing where we were being taken, only that the column was heading towards the front gate. Lutschi and his brother Kurt and I were marching along past the Blocks and, once again, luck was on our side, for as we marched passed a Block our friend Paul Jellinek recognized us and quickly pushed us into a Block and said, "Climb into a bunk and stay there". Paul went through Jawischowitz with us, and when we were taken to Buchenwald, he was immediately integrated into the well-organized group of the internal camp administration of political inmates. This privileged treatment was due to his political background. We were absolutely drained and would not have been able to survive another march. We were walking skeletons, always hoping that it would not be long before the end of our suffering, with no food, no showers or decent washing for months, the lice were eating us up, that is how it felt, when I used to put my hand into my shirt I could scrape the lice off my body.

On the 11th of April the message boomed over the loudspeaker system throughout the camp, "Alle SS-Angehörigen sofort aus dem Lager" (all SS members immediately leave the camp). We knew then that the moment had come and that this was our liberation! The sound of gunfire became louder and louder with bullets flying everywhere and as we looked out of the windows of the Block we could see the American Army tanks move up the slopes towards the camp, my good friend Lutschi pulled me down shouting at me, "You want to get killed now at the last minute?". We fell in each others arms and cried tears of joy, the emotional impact it had on us all lasted quite some time, for we could not believe that it was all over and that we were getting out of this hell alive. It took a long time for that feeling to sink in and for us to fully grasp that it was really happening. Much later we, the survivors, realized that we were reborn! Later on we found out that 150 political inmates armed with rifles stormed out of the camp to apprehend as many of the SS guards as they could, before they escaped into the woods. They were to be handed over to our American liberators. These weapons had been smuggled into the camp, in pieces, at extreme risk, bit by bit over the years, by inmates who worked in the munitions factory. They were well-hidden over the years and assembled when the time came for the right purpose.

The first American soldier who entered the camp was carried shoulder-high through the camp, with jubilation and hailed like a redeemer, a guardian angel, for he represented to us the liberators. What the Americans found was for them a most horrible sight and hard to understand – that such conditions and suffering could exist in our time and age, in the centre of cultured Europe, perpetrated by supposedly civilized and educated people. The heaps of dead, emaciated bodies were lying everywhere, with the stench of rotting cadavers pervading the air, the Americans had to use bulldozers to move the bodies into mass graves in order to avoid diseases from breaking out. For a lot of our suffering comrades the liberation came too late, daily many were dying, they could no longer recover. Although food was brought to the camp and medication was gradually made available, the bodies of many could no longer react. The Americans collected this food from nearby farms and, although well intended, it was far too rich for our bodies to absorb, consequently lots of comrades got diarrhoea. I was not exempted from it either, our constitutions were not used to fat and meat etc.

Shortly after the liberation, Lutschi and I were stricken with typhus fever, which meant lying up with a high temperature for three weeks in the camp hospital, with many others suffering from the same disease. Lice are the carriers and transmitters of typhus fever, and since we were riddled with them at the time of liberation we finally caught the dreaded disease. We were lucky that we did not catch this disease during the concentration camp time; it would have meant the gas chamber, since the recuperation was too long to be fed and kept without work, no use to the Nazis.

While the camp was still in the state the way the Americans found it at the time of the liberation, they took truck loads of German civilians, at random, from Weimar through the camp to show them what the Nazis had perpetrated. The US Army doctor who guided them through the experimentation Block (which was sealed off within the camp during the Nazi time), cynically told them, "In our uncivilised America we use guinea pigs for medical experiments, in your civilised Germany you use human beings". The Germans who were shown all the remaining horrible vestiges maintained that they did not know that this existed, yet they saw us, looking from their windows as we were marched through their city, Weimar, in the miserable state we were in with the armed SS guards on either side of our column, so how could they deny this fact, if they had said nothing at this point, it would have been better.

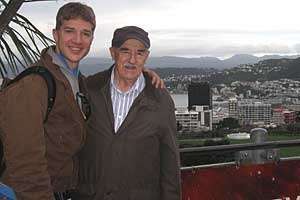

After the liberation and discharge from the camp hospital, Karl said goodbye to his friend Lutschi, who went back to Vienna while Karl was going back to Brussels with two other comrades, Erich Jensen and David Gold, both from Vienna, too.

In Belgium our first stop was in Hasselt where we were received with a big welcome by a team of ladies at the station with food and drinks. They treated us like returning heroes, this was a further good feeling of being free. We then continued our journey and got off at Brussels, there we parted and went our separate destinations, to meet up later on. From Gare du Nord (northern railway station) I walked to Rue Godefroid de Bouillon which was nearby. My legs were giving way as I walked up the hill to meet my family, after two and a half years in hell. I rang the bell in Rue Godefroid de Bouillon number 4, and I was home!!! [

]

It was always my intention and on my mind, that we owe it to the ones who perished in such an unspeakable and horrible way, to impart the facts of what happened in the concentration camps, for future generations to know, first hand, from survivors, what went on in this hell, in order that a denial of the slaughter of our people will never be given the slightest credence. Sadly there are people who are trying to pervert that part of history, by denying that it ever happened, some reduce the numbers of the ones having been put to death. How can anyone possess the audacity to deny these statistical facts and how can anyone say, "How come so many survived?", as if to say that not that many were exterminated? Only a sick mind can make such allegations. All the more reason why it is up to us, the remaining living survivors, and life witnesses to that horror, to relate the truth of what happened, while we still can, this is the main purpose of my personal testimony. I remember all incidents clearly; our children and grandchildren should be told what went on during that terrible time, it must never be forgotten. For anyone who went through it, such an experience is impossible to forget.

During the first few months back in Brussels, when we were getting used to becoming free human beings again, we met with some of the comrades from Jawischowitz, who had also returned to Brussels. Lutschi Weinber came from Vienna to see his family in Brussels, and so we met up again, after having parted in Buchenwald a few weeks earlier. A few of us went to Antwerp to look up the four Taub brothers, who were with us in the camps, all four miraculously survived the camps and came back, sadly their wives and families perished in Auschwitz. On the 22nd of August 1945 a gathering was held, which we all attended, to commemorate the heroic death of Mala Zimetbaum, who was executed one year earlier in Auschwitz. [11] My mother, who survived the war in England, came to Brussels and, after a short stay, my sister Margit and I went with our mother to London, there I awaited my permit to join my brother in New Zealand. I managed to keep in touch with some of our former comrades after emigrating to New Zealand. A short time before leaving Brussels I went with a friend, Erich Reischer, to a place where he had his radio fixed up, when we got to the place where the person lived who repaired his radio, I read "Mademoiselle Treitler" on the door. My friend knocked and a young woman opened the door, I spontaneously asked her if she knew a Pauli Treitler. Tears ran down her face and she yelled, "Yes, that is my brother", she immediately asked me if I knew where he was, I told her that I saw him for the last time in early April. I did not and could not tell her in what a horrible way her brother perished. Every so often in history our people had to face adverse situations.

The Holocaust was the most fierce and brutal that befell us, in the middle of civilized Europe and the 20th century. My friend Lutschi told me before we parted, "Do not tell anyone what you went through or what you have seen, no one will believe you", "es wird dir keiner glauben". That no one can grasp the horror of our experience I can understand, however, those who deny that this took place, I pity and feel sorry for their chosen blindness to these facts. I quote here a statement made by the German philosopher and psychiatrist Karl Jaspers, "That which has happened is a warning, to forget it is guilt. It was possible for this to happen and it remains possible for this to happen again, at any minute". [

]

The trauma of having to live through such a hopeless situation is an experience that can never be forgotten and remains in ones memory for life. From the time our mother left for England, my unforgettable, loving and beautiful sister Edith cared for us all, she cooked, washed, mended, prepared my lunches I took to work, with the little we had she always managed to put a meal on the table, and in general kept house for us all, never did I hear her say one word that it was too much for her, a kinder soul one could not find, innocent and never hurting anyone, then at 18 years of age, together with my father, to be murdered because they were Jews. As long as I shall live I will never understand nor grasp how people can be made to hate to the extent, as to resort to such a heinous aberration of putting humans to death for their religion. This enormous barbaric crime reeks to high heavens. How could a whole nation be made to hate to such a degree? In order to be instrumental to perform these horrible atrocities on a genocidal scale, and not wake up to the terrible criminal wrong they were led to perpetrate.

For me having been able, after the liberation, to get away from Europe as far as possible, from the places where it all happened, was the best healing process. New Zealand and Australia are both havens to live in and I felt reborn in this part of the world, I am grateful for having been given the opportunity to start a new life and a family, and my children brought me lots of naches [12] with all my lovely grandchildren, they are the future and continuation of our lives, I am truly blessed!!!

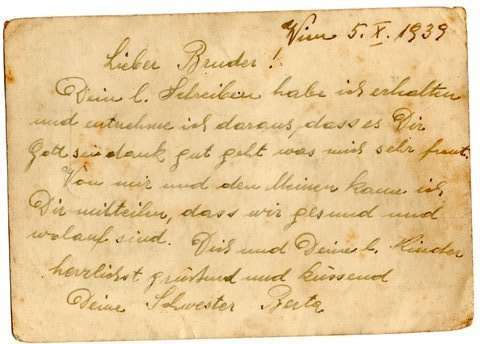

In memory of my Father!

Here you can read an interview with Karl Fox in the Austrian Newspaper "Der Standard".

[1] The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was sent to the Franco-Belgian border after the German invasion of Poland on 1st September 1939. Following the German Army's "Blitzkrieg" starting in May 1940, the BEF were pushed back and could eventually be evacuated from the French city of Dunkerque (Dunkirk) to England.

[2] This liberation started on 6th of June 1944 ("D-Day") with the landing operations of the Allied invasion of Normandy.

[3] Kapos were concentration camp prisoners appointed by the SS who had certain lower administrative functions. Often prisoners convicted on criminal charges, they received more privileges than normal inmates and treated their fellow prisoners very brutally.

[4] Jawischowitz was a sub-camp of Auschwitz in the northern part of the Polish village of Jawiszowice where the prisoners had to carry out slave labour in the Brzeszcze coalmine.

[5] Lagerführer: camp leader. The first camp leader of Jawischowitz was SS corporal Wilhelm Kowol (July/August 1942-August 1944), followed by SS master sergeant Josef Remmele.

[6] In September 1943, after Italian dictator Benito Mussolini had been ousted, the Germans invaded Italy and the deportation of Italian Jews to extermination camps started. An estimated 7,500 Italian Jews became victims of the Holocaust.

[7] Primo Levi (1919-1987), Jewish-Italian chemist and writer, survivor of Auschwitz.

[8] Of the 55,000 Greek Jews living in the German occupied city of Saloniki (Thessaloniki) when the Germans invaded the country in April 1941, more than 45,000 were sent to Auschwitz in 1943. Only about 2,000 survived.

[9] Revier, Krankenrevier: sickbay.

[10] German field marshal Friedrich Paulus (1890–1957) surrendered to Soviet forces in January 1943 after having lost thousands of soldiers at Stalingrad. During his time in Soviet captivity he became a critical voice of the Nazi regime and joined the National Committee for a Free Germany.

[11] Mala Zimetbaum (1922–1944) was a Belgian woman of Polish Jewish descent who was sent to Auschwitz in September 1942. In June 1944, she managed to escape with her Polish friend Edward Galinski who was dressed as an SS guard. Both were captured soon after and brought back to Auschwitz were they were to be put to death in front of the assembled prisoners. On 15th September 1944, right before her execution, Mala slashed her wrists with a razor blade and slapped a guard with her bloody hands. She probably died on the way to the crematorium where she was to be burned alive.

[12] Naches (Yiddish): joy.