Lucia Heilman

Hidden in Vienna

Lucia Heilman was born in Vienna on 25th June 1929. With the help of a friend she and her mother survived the Holocaust hidden in various places in Vienna.

When my mother (the late Dr. Regine Hildebrandt, born Treister) met my father (Dr. Rudy Kraus) in 1927 she got also acquainted with his best friend Reinhold Duschka. They met at a Viennese youth organization where Rudy and Reinhold went mountain climbing together.

The three of them became very good friends. My mother had a Ph.D. in chemistry and was working for a big hospital in Vienna. My father was an engineer, working for the German company Siemens. Reinhold Duschka was an artist, creating vases, bowls, and decorative items made out of brass, copper and other metals.

In 1938, when the political situation in Austria became unbearable, my father went to Iran (Persia) for Siemens and wanted my mother and me to follow him there as soon as he was settled. But before we could arrange the necessary papers for our departure, World War II (1st September 1939) broke out. This made it impossible for us to get transit papers to Iran.

My mother managed to obtain a visa for the USA, but we had no money for the passenger tickets. At the same time the deportation of the Jews had started in Vienna. Trucks would stop in front of a house, the driver – a Gestapo member – forced the Jews who lived there onto the truck. They were then taken to the train station, from where they were brought to the death camps. My grandfather, who lived with us and took care of me while my mother was at work, as well as my best friend, Erna, who lived next door, were deported by these horrific Gestapo trucks.

Erna and her family were forced to mount the truck. She was a little girl (like I was) and could not easily mount the huge vehicle – she fell from the ramp. Unbelievably, she was run over by the truck driver, who did not care that a Jewish girl was under the wheels of his truck. This happened on 10th November 1938.

Together with thousands of other people, my grandfather was detained in a soccer stadium in Vienna until a decision had been made where he would be taken. [1] Nobody knew for how long they would keep the people in the stadium. Days went by, before we received the first postcard – the first of two that we would ever receive. He asked us for several items, such as blankets, shoes, etc. I accompanied my mother to the stadium to bring him food and the things he had requested. We waited in a very long queue and at the end of the line; everybody had to hand their parcel or suitcase over to the guard in charge. We were told that everything will be given to the person it was intended for. Some people in the waiting line were beaten only because they had spoken to one another or did not form a straight line. A few days later we received the second postcard in which my grandfather thanked us for the things we brought to the stadium. I never saw my grandfather again ...

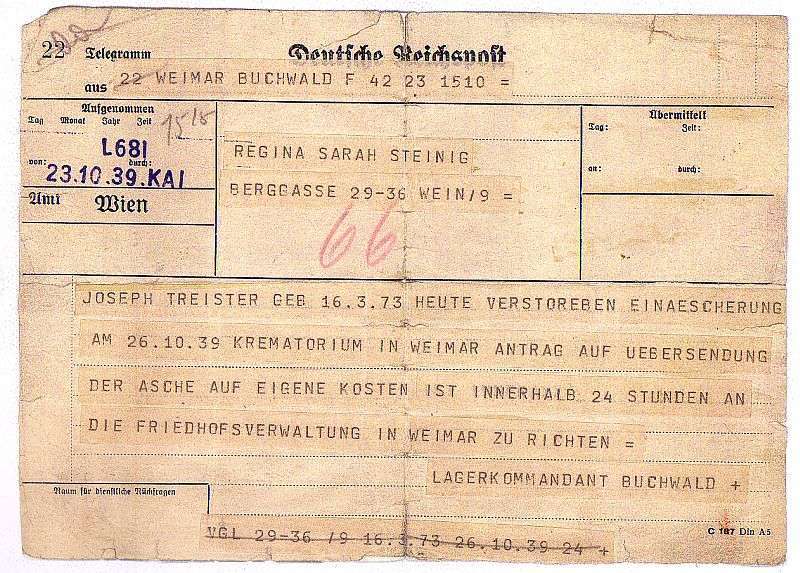

On 23rd October 1939 we received the following telegram:

"Joseph Treister, born 16th March 1873, died today, cremation on the 26.10.1939 crematorium Weimar, plea for transfer of the remains has to be made to the administration of the cemetery within 24 hours at ones own expense. Camp Commander, Buchwald."

In 1938 anti-Semitism was the official state policy and the situation for Jews in Europe became unbearable and increasingly dangerous.

I was nine years old and went to school. One day the director of the school came to my class and asked all Jewish children to leave. We packed our books and while we left he yelled "Juden brauchen nicht zu lernen" (Jews don´t need to be educated). I felt deeply hurt and embarrassed.

From that day on, my mother and I were forced to wear the yellow "Judenstern" (Star of David) on the left side of our coats. [2] The first time I went out onto the street with the star on my coat, some older boys saw me and immediately beat me up. I was screaming for help but nobody cared. On the contrary, passersby encouraged them to beat me even harder. When they finally stopped I ran home crying and aching all over.

My mother, my grandfather and I lived in Berggasse, a street in Vienna's 9th District. One day in 1938, a couple came to our flat, simply walked through it, and bluntly told us that we have to leave within a week – they liked the flat and wanted to move in. We were very poor and did not own many things, but we were forced to even leave those few valuables behind. Everything that happened was difficult for me to understand – I desperately tried to keep all of my little toys and books. But I was only allowed to keep one Teddy bear. We were forced to move to an apartment, which had been assigned to us by the Nazis. We had to share it with ten other people until 1941/42.

After the confiscation of our flat in Berggasse my mother desperately tried to find a solution for us, because it became very clear to us that we had to hide if we wanted to survive. Reinhold Duschka offered to hide both my mother and me in his workshop. By offering to save our lives Reinhold risked his own life. The Nazis immediately imposed the death sentence onto anyone who provided a hiding place and food to Jewish people. Reinhold was left unmolested by the Nazis, as he was considered to be "Aryan". Obviously they had no clue about his political attitude, which was totally anti-Nazi. He had a two-room workshop on the 4th floor of a house in Mollardgasse, in the 6th District. This building only housed workshops for professional craftsmen and therefore offered a good hiding place. Reinhold's private apartment was situated in another district of Vienna. [...]

In one of the two rooms of his workshop, Reinhold built a wooden compartment for us to hide in. This was where we slept. When a customer came to buy one of Reinhold's works of art or when the doorbell rang, my mother and I had to hide immediately. During those moments we stayed next-door – absolutely silent and barely breathing. Even today the ringing of a doorbell or the telephone gives me a cold chill.

Our "bed" was the stone floor that we covered with blankets, which were well hidden during the day, so nobody could imagine that somebody lived there. The daily routines became very difficult in such a situation. Going to the toilet was not possible; we had to use a bucket which was emptied by Reinhold in the evening. Moving around was also not possible because there was a guard in the building who heard every footstep. Food was not always available. Clothing was almost impossible to buy and since I was still growing, I hardly ever had anything that fit me. During all those years in hiding, there was no other child I could play with or speak to. When I looked out of the window I often cried – I imagined another world and longed to be outside. I still had my little Teddy bear that I kept after the Nazis confiscated our flat.

But there were some situations when we had to leave our hiding place – for example, the day I had a terrible toothache. Of course we did not wear the "Judenstern" on our clothes; almost all Jews had been taken to concentration camps. Reinhold took me to a dentist who obviously did not ask too many questions and relieved me from my pain. I even went there alone for treatment several times and was luckily never asked any questions.

My mother tried to teach me those things that I would have learned at school. Since I loved to read, Reinhold brought me many books from a public library. Reading enabled me to escape into another world. In our hiding place there was a radio through which we got some information about what was going on in Europe. Later we listened to the allied radio channel, which was absolutely forbidden.

In the beginning we hoped that this situation would not last long. It was simply unimaginable that such a horror regime could last long. But we were proven very wrong. While we were hiding, Reinhold taught my mother and me how to prepare the metal for his work, which sold very well. The customers liked the vases and the other pieces of art that he had made. He spent the money to buy food for us on the black market.

In the winter of 1944 the house in Mollardgasse was bombed and burned out completely. I remember that this happened on a Sunday. Reinhold had gone mountain climbing and the entire building was almost empty when the allied air strikes started. My mother ran to the shelter room with me. It was the first time during the years of the war that we dared to hide in the air raid shelter. Usually we stayed in the workshop during the air strikes, fearing that the other people living in the house might want to find out who we are. Fortunately, nobody asked us any questions and after some hours Reinhold found us alive. We fell into each other's arms, incredibly thankful that we had survived.

Reinhold had to find a new place for us to stay in. He had a small bungalow in one of the garden suburbs of Vienna where we were able to stay for a short while. When we arrived there I saw that the entire city was in flames after the bomb attacks.

Reinhold told the neighbors, that we were his relatives from Germany. During the few winter days we were there, we hardly ever left the house. It was clear that we could not stay there long – it was much too dangerous and much too cold.

Shortly after the air raid we returned to our old hiding place and searched the scorched rubble for items we might still be able to use. We found the metal tools from Reinhold where the wooden grips were missing because they were burnt. And we found the praying books from my grandfather which my mother took with her to the hiding place. They were unharmed, although everything else was burnt!

With the help of a good friend, Reinhold found a small shop in the 6th district with an adjacent underground cellar in which we were allowed to stay. My mother and I spent the last month of the war in this humid cubicle. It had no windows, no daylight, and no heating. We could not stay in the shop because people could see us through the windows from the street. I remember this hiding place as so dark and so cold ... impossible to describe. For days on end we stayed in total darkness and were filled with fear. Even until this very day, I cannot bear total darkness.

The Russians arrived in Vienna on the 13th April 1945. And they finally brought freedom! We were so happy that we cried. The fear was gone, no more deportations and gas chambers, no more denunciations, no more SS and Gestapo, no more yellow stars. Seven years of fear for one's life had ended. But we knew that the end of the war did not change the Austrian mentality ...

The Russian army gave my mother and me an apartment and they helped us obtain our personal documents, which were issued by officials of the city hall. After seven years I now had a real bed to sleep in and a toilet. Thanks to the Russians my mother took up her work again and I was able to go back to school.

It is impossible to write about the fears my mother and I had of all the horrors human beings could think of, which became reality through the Nazis.

Reinhold Duschka as well as many miracles rescued our lives. Reinhold acted out of pure morality and his strong sense for justice. He was a dear and close friend of my father and he hated the Nazis. It was clear to him, that my father had desperately wanted us to join him in Persia but on account of the circumstances this turned out to be impossible. Therefore Reinhold took over the responsibility for us. As a man with a strong moral understanding he could not accept the injustice against human beings and wanted to prevent the Nazis from murdering us.

Another explanation why Reinhold acted in such remarkable and exceptional way was the strong tie that he and my father had through their mutual and numerous mountain climbing experiences. Alpinists are always prepared to risk their lives for one another and to place their trust in one another. Reinhold took the responsibility over our lives when his friend – my father Rudy – could no longer do so.

In 1945, immediately after the war had ended, my mother started to work again. She took up her job as a chemist at the same hospital where she worked before the war broke out and where she had lost her job because she was Jewish. My mother had two brothers of whom only one survived. All other relatives perished in the Holocaust.

I was 15 years old in 1945 and was allowed to go to school again. When the Nazis forced me to leave school I had only attended the first three elementary school classes. During the war my mother did her best to teach me as much as she could, but of course we did not cover all of the subjects my classmates had in school.

Back at school, I finally met young people to talk and play with. I was no longer alone. I was the only Jewish student in class and for most of my classmates I was the first Jew they ever met. For the teachers I was simply the "new one". When they asked me which religion I had and I answered "Jewish", they could not hide their shock. In their opinion, which was strongly influenced by the Nazi propaganda, the tight murderous network of the past seven years had killed all Jews. Some teachers were nice, some of them too pitiful and some of them did not hide their anti-Semitic attitude. I was surprised that nobody ever dared to ask how I had survived; they all avoided touching any subject that concerned those last seven years of horror.

Private tutors helped me catch up with my schoolwork, which I had missed out on during my years as a hidden child. At 4:00 am I got up to work and at 8:00 I went on studying at school. I was so eager to learn that I caught up very easily and quickly. I enjoyed everything – going to school, being allowed to enter shops that used to have the sign "Juden unerwünscht" (Jews unwanted) on their doors, and sitting on park benches that were marked with "Nur für Arier" (For Aryans only) during the war. I started to feel like a human being again. I completed school and graduated with the Austrian "Matura" (School-leaving certificate) and went on to study for my medical degree.

With the end of the war and the death of Hitler, I noticed that suddenly everybody claimed to have been against him anyway and that they never believed that the "Reich" would ever be victorious.

I met my (late) husband in 1945. He had come from Poland and Russia and we married in 1953. Luckily he was far away from the Nazi regime and survived the years of the war living in eastern Russia. We settled down in Vienna, the city in which I had endured the most terrible years of my life. This was my husband's wish after we had attempted to move to Australia and Israel. I must add that it was a very difficult decision for me to stay in Austria. But it was the only country in which I was able to study Medicine, because there were no enrolment fees at the University. Neither my family nor my husband would have been able to finance my studies elsewhere.

Many people asked me how I could bear to stay in Vienna after everything I had experienced. I must admit that weakness and the love to my husband were the main reasons that I stayed in this city. My husband and I have two daughters and two grandchildren.

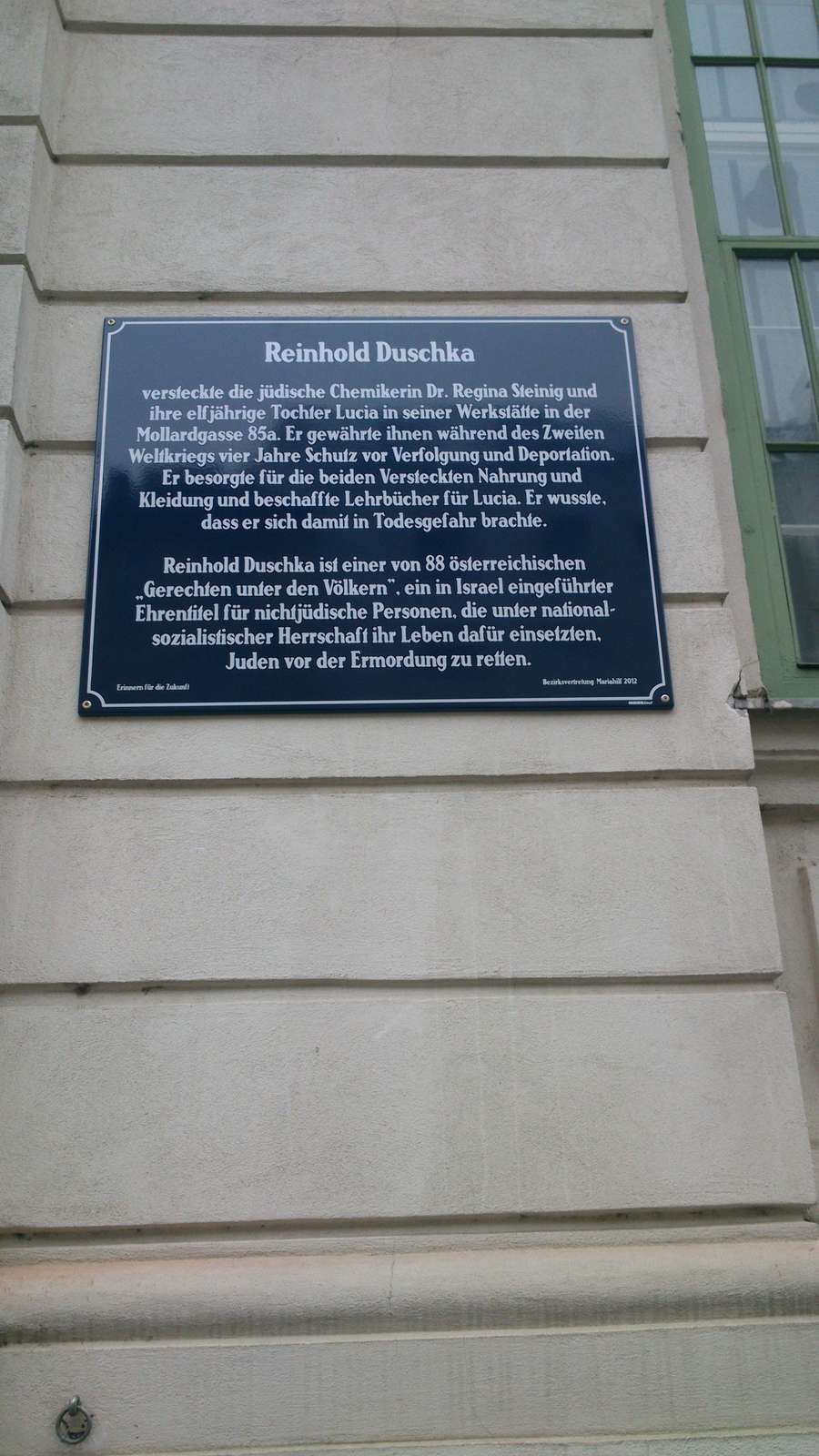

The house, in which the workshop and our hiding place were situated, was completely restored after the war, and Reinhold Duschka worked there until he retired. He was a hero, my guardian angel and one of the very few Austrians who displayed so much courage! [...]

My mother and I stayed in regular contact with him after the war and my feelings towards him were the same as to a father. For many years he refused to be nominated as a so-called "Righteous Person", a very honorable title awarded by Yad Vashem [3]. He was worried, that such a title would still cause difficulties for him in Austria – even 50 years after the war! Finally in 1991, at the age of 89, he agreed to be nominated and was subsequently chosen and honored as a "Righteous Person" by Yad Vashem.

The original version of this life story, which was written by Lucia Heilman with the help of her daughter Viola, was first published in the magazine "The Hidden Child. Newsletter Published by Hidden Child Foundation / ADL. Vol. XIV/2006, p.5-6 and 9".

[1] In September 1939, after the German invasion of Poland, more than 1,000 male Jews of Polish origin were arrested and imprisoned at the Viennese stadium for three weeks. More than 400 of them had to undergo anthropological examinations, before they were all deported to the concentration camp Buchenwald. Only a few of them survived the Nazi regime.

[2] From September 1941 on, Jews had to wear a "Judenstern" or "Davidstern" on their clothes.

[3] Yad Vashem - The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority - was established in 1953 as the world center for documentation, research, education and commemoration of the Holocaust and is situated in Israel. You can find further information about Yad Vashem on the website of Yad Vashem.