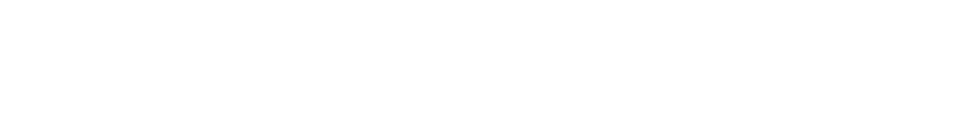

Rudolf Karger

I was a child of Spiegelgrund

I was born on 16th July 1930 in Vienna and I grew up in a municipal apartment in Ottakring, consisting of one room, a smaller room and a kitchen with no hot water.

Most of the time, there were twelve people living there, four of us children. Of the eight adults, generally only three were in employment, the others didn't have a job, they were unemployed. They weren't good times.

When the German troops marched into our beautiful Austria on 12th March 1938, amid great celebration and fanfare, for me and my family it was nothing to celebrate. Firstly, on the night of 12th March 1938, my uncle was picked up from the apartment and deported to Dachau, because a few days before the troops marched in he had dared to say in public: "Who needs A. H. [1] in Austria?" He was grassed up [2] and spent two years in Dachau.

My two older sisters, Alice, born in 1929 and Elfi, born in 1927, and I were born out of wedlock, which was considered a disgrace at that time. My mother died in 1936 at the age of 29, when I was six years old and my father wasn't around for us children. When my sister Elfi was born in 1927, my father was only 16 years old and my mother 19. For whatever reason, my father was unwanted by my mother's family and my mother was unwanted by my father's family. And so my two sisters and I grew up without parents. My grandmother on my mother's side had parental authority, but as we were born out of wedlock, the Youth Welfare Office was our legal guardian. In 1938, the Youth Welfare Office was renamed the Reich Youth Welfare Office and we three children were undesired by the National Socialist regime, although we were neither mentally nor physically disabled.

Participation in the "German Youth" [3] was compulsory, but I didn't go. One day, in Thaliastraße, a column of the Hitler Youth marched towards me with the German flag. Aged eleven, it didn't occur to me to salute the flag with my arm outstretched. Immediately, the leader of the column separated from the rest and struck me twice because I didn't salute the flag. One time I was picked up by the police after 9 pm on my way home – even at the age of ten, I enjoyed going to the theater. Again I was beaten and my grandmother had to pick me up from the police station late at night. Several times, I also spent the night sleeping on the attic staircase when my uncle was at home. I was terrified of him because he violently beat me for no reason. So I waited in the attic until he left again in the morning. This was all reported to the Reich Youth Welfare Office – were these the reasons for sending me to Spiegelgrund?

And so my guardian – the Reich Youth Welfare Office – cleared the way for me to be sent to the children's institution "Am Spiegelgrund". There, A. H. had doctors and assistants who carried out the party program of exterminating everything which was not fully adequate for his "Greater German Reich". Skilfully, his assistants displayed their willingness to torture children of both genders. We had to endure much suffering and always be ready to die.

On 1st September 1941, I was moved from the child collection point in the 9th district, Lustkandlgasse, to Spiegelgrund. The 1st September was a beautiful fall day. I don't know which pavilion I was brought to. It was either pavilion 8 or 9. They all looked the same from the outside – they were brick buildings, as they still are today. When I was led into the pavilion, there was not a soul there. So I was able to look around and assess my new surroundings. The doors were locked and there were bars on the windows. The pavilion consisted of a long corridor, a day room, a bathroom with showers, a big dormitory with around 25 beds, a small kitchen and a workroom, all spotlessly clean. At around 4 pm, I heard a loud babbling. The door was opened and about 25 boys of my age came in, accompanied by two nurses, who actually seemed nice. But by the next day, I had realized that they were really very brutal to us.

Some of the atrocities committed against us there are already known. But I would like to recall some of the suffering that I had to endure:

There were beatings every day. Night after night, we had to stand at the foot of our beds, dressed only in our night shirts, which only reached down to our knees – in summer with the windows closed and in winter with them open.

Forced marches. Once we even had to march as far as the police station at the Praterstern. One of us boys ran away and we had to collect him. Spiegelgrund – Praterstern and back again, Praterstern – Spiegelgrund. When we all arrived back at Spiegelgrund, we were completely exhausted. All of our anger was directed at the boy who had escaped and whom we had had to bring back. There were no friendships between us boys, we were galvanized into hating each other. When we were punished, we were always told we had "him" to thank.

Once a week we were given porridge, but not with full fat milk butter and chocolate on it. No. Only with skimmed milk, thin and with lumps. We had to eat that. One of us never managed it. Two nurses stuffed him – opened his mouth, held his nose [and shoved in the food]. He always threw it up on his plate and the whole process lasted until the plate was empty and he had swallowed it all. Meanwhile, we had to watch while standing at attention.

Then we were given the famous vomiting injections, which caused us to throw up and suffer terrible pain. When Dr. H. Gross [4] was questioned during his trial [5] as to why he had committed this crime against us, he said calmly that the injections were harmless, they were just to stop us from becoming too high-spirited.

In 1941, the whole group and I "celebrated" Christmas Day. A Christmas tree was put up in the day room, it was completely bare, and we had to stand at attention in front of it for hours. That was my and our Christmas Evening. There was nothing holy for us, let alone presents.

Standing to attention for hours on end, that was a matter of course, day after day.

Once a month, my grandmother was allowed to pay me a short visit. In my presence, they always explained to my grandmother how well they cared for us. That they didn't beat us. I never told my grandmother what they did to us, of the pain and the suffering they inflicted on us. If I had mentioned it, my grandmother would have run to the director's office to complain about what was done to us. And it can't be ruled out that she would then have been deported to a concentration camp.

On one trip outside, I had the opportunity to escape. Out of homesickness I ran home to my grandmother. Less than two hours later, the door bell rang. Two nurses from Spiegelgrund were there to take me back. They assured my grandmother that there would be no consequences for me. But I already knew what would happen to me – the same as happened to everyone who escaped. And I wasn't spared. Barely was I back at Spiegelgrund, I was beaten. So many blows to the head, I thought I had gone deaf. The whole group had to stand at attention at the window in silence. My clothes were torn from my body, and in front of the whole group my hair was shaved off – to serve as a warning. That used to be one of the worst punishments. They didn't only cut the hair, they tore it out. Bloody and bruised, I was then dragged into the bathroom. The bath had already been filled with cold water for me. I was pushed into the bathtub and pushed under many times, so that I couldn't breathe. I fought back, gasping for air and swallowing water and in my desperation I pulled the plug out of the plughole. I was then pulled out of the bathtub and put under the cold shower for a quarter of an hour. It was horrific; I could hardly move and was thrown from the bathroom into the corridor. Crawling on my knees, I had to crawl past the row of my attackers, being beaten all the while. Then they pulled a night shirt over my head and I was taken to the Children's Special Department 15 or 17. The pavilions where there were deaths on a daily basis.

I still have hazy recollections of being put in a cell. I was so hungry and was given painful injections. I only saw men and women dressed in white and who mistreated me. I don't know for how long I was in pavilion 15 or 17. Today, I know that I was in the clinic of Dr. H. Gross, who removed the brains of the tortured children in the name of science. I remain convinced that I was only spared because I had the wrong kind of brain for Dr. H. Gross. I was then taken to pavilion 11 to join the punishment group. There were about 20 boys there who had fallen into disrepute and who were considered even worse than those in pavilions 7 or 9. The punishments were the same as in pavilions 7 and 9. The only difference – no female nurses, but males. I particularly remember that, among other things, for hours on end we had to pull the sheets off the bed and then put them back on again, perfect to the millimeter.

I had already been in Spiegelgrund for a year, when on 4th September 1942, with 70 or 90 other youths, I was unexpectedly taken to the Nazi reformatory in Mödling. It was the former Hyrtl'sche Orphanage, which had been converted into a reformatory for us "naughty children". There we were subjected to a strict, mainly military drill and brainwashing. We had to learn everything by heart – about A. H. and his political ideals for the "1000 year Reich".

On 7th July 1943, I was allowed to return to my grandmother. She always tried her best to get us three children back home with her.

My time and my suffering at Spiegelgrund remain alive in me today, as if it had all happened yesterday and not 69 years ago. The experiences at Spiegelgrund were inhumane and the reports of the time glossed over them. We were used as "guinea pigs": we were given various injections, medication was tested on us, we were stood under cold showers and in winter we were wrapped up in wet blankets and much more. This painful one year stay at Spiegelgrund destroyed my childhood, my youth and also my future.

My stay was also cruel because it prevented my further education. There was no school. Scarred by Spiegelgrund, I stood before a hopeless future. The one time payment from the Austrian National Fund in no way repairs what has been done to me. I was no genius, but also not an idiot. But the stay in Spiegelgrund took away my chance of a better future. I remained at a disadvantage both professionally and financially.

As a contemporary witness, I occasionally work in schools to speak of the monstrous [crimes committed] against children and young people during the National Socialist era. The stay in Spiegelgrund brought with it suffering, pain and death. For the regime, we were undesirables, inferior, unworthy of life. And I find it very beneficial when people […], with a lot of effort and time, highlight these crimes of the Nazi regime and ensure that they are never forgotten.

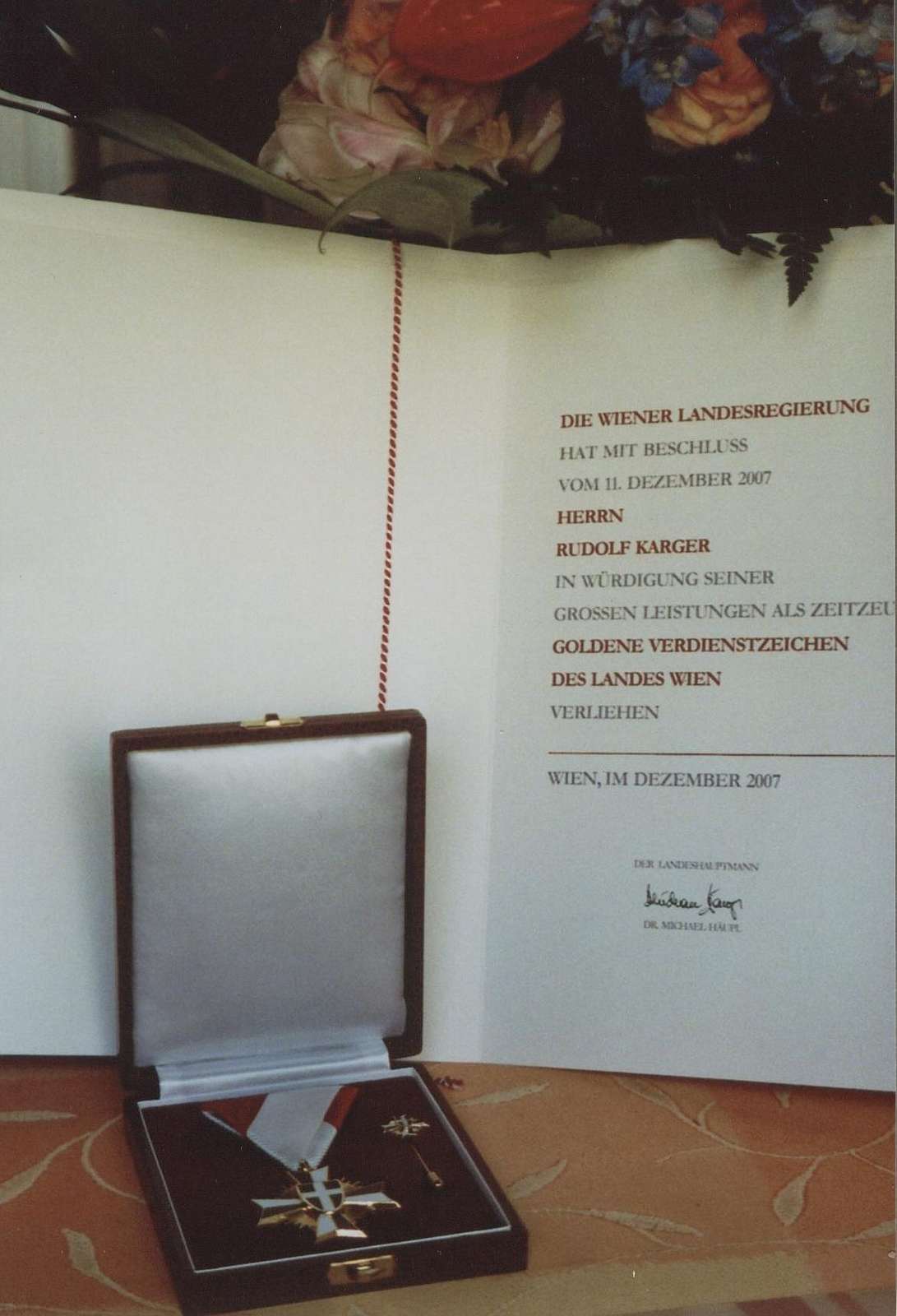

As a result of my activities as a contemporary witness, I was honored by the Vienna Provincial Government in recognition of my great services as a contemporary witness, and received the Gold Order of Merit of the Province of Vienna.

This article was first published in: Renate S. Meissner on behalf of the National Fund (Ed.): Lives Remembered. Life Stories of Victims of National Socialism. Vienna 2010, pages 200-206.