Bartholomäus O.

I was so terrified, I couldn't speak

The Carinthian Slovene Bartholomäus O. was born in 1936, the fifth of eight children. His parents owned a small farm. His father also had to work as a forestry worker to supplement their income.

Mr. O.'s childhood was characterized by terrible fear – of school, where he was only allowed to speak German, and of the uniformed police, who mistreated him and put his family's house under observation in order to expose his family's support of the partisans. As a result of his fear of strangers at the farm, he didn't dare to return home, which – in addition to the psychological strain – brought with it a terrible illness with life-long consequences.

My father was called Batholomäus O. and was born on 27th July 1896. My mother Helene, née P., was born on 2nd May 1900. My father was a forestry worker at the company "Lasch". My parents had inherited a small farm from my grandfather and lived in Zell-Freibach. As my father was already too old to be conscripted into the German Armed Forces, he had to serve in the Zell-Pfarre Air Defense. So he often spent a few nights a week away from home and my mother was at home alone with us children. I was the fifth of eight children.

In 1942, I started elementary school. As we only spoke Slovenian at home, I found school very difficult. In the first grade, I had a teacher who was understanding of my situation. In the second grade, however, it got worse and worse. Police were accommodated in the first floor of the building, above my classroom. One time, in the second grade, I was standing in front of the blackboard and there was a shot upstairs. The bullet went through the ceiling and became lodged in the blackboard, right next to me and the teacher. It only missed us by a few centimeters. I was so terrified, I couldn't speak. The teacher also collapsed in terror. I became so scared of school that I cried and shook everyday when I had to enter the school building.

A few days later, with great disinclination, I arrived at school. There were lots of policemen lined up in rank and file in the square in front of the school building. We had to greet each one with our lifted arms outstretched in the "Hitlergruß" – it was compulsory. I went past them and saluted, as I had been taught at school. Apparently, I was doing something wrong, for suddenly a policeman stepped out of line and slapped me in the face so hard that I went flying and bled from my nose and my right ear. The policeman grabbed me, set me on my feet, and said: "Tell me, how do you salute Hitler correctly?" I stretched my arm out high and shouted "Heil Hitler!" and he chased me away. Now I didn't want to go to school at all. I couldn't concentrate and was terrified.

One day, in winter, I was on my way home from school. Shortly before I reached my parents' house, I saw police marching along the street. I was so terrified that I ran across the Freibach stream, which was cold and partially frozen, and up the hill on the other side to get out of their way, although I was nearly up to my neck in snow. Then I walked alongside the woods to my parents' house. When I reached the door, I heard unfamiliar male voices inside. I thought it was the police. So, wet through, I ran to the barn and hid. Then, I fell unconscious. My mother was already worried because I hadn't returned home. She looked outside and saw footprints leading from the woods to the barn. That was how she found me. I caught pneumonia and orchitis and kept slipping in and out of consciousness. As the doctor couldn't or wouldn't come, my mother started lighting candles. She thought that I wouldn't survive and she prayed and prayed. In the end, I slowly recovered but I was no longer in a fit state to go to school. That is why I never got further than the second grade.

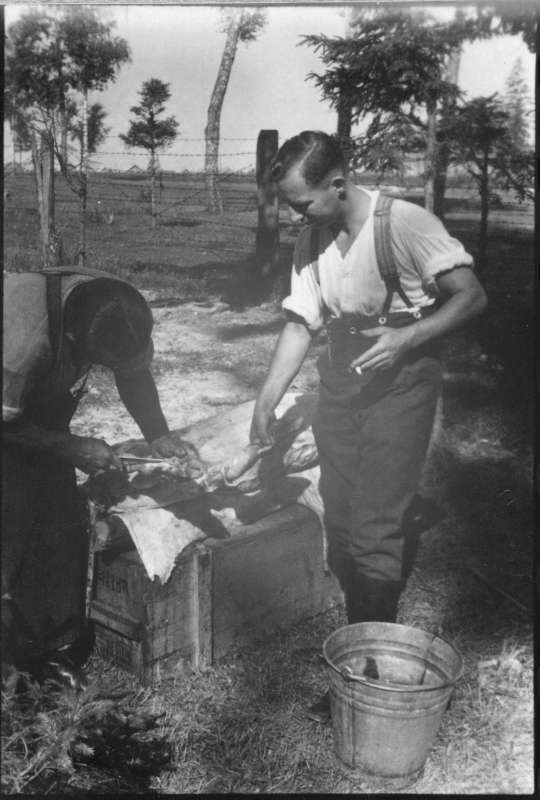

From 1943, the partisans often came round to pick up food. Most of the time, they came silently in the evening or during the night. My parents didn't have much themselves, but they gave them what they could. It was strictly forbidden to help the partisans.

One day, my father gave the partisans a pig. But someone betrayed him and the Gestapo came and arrested him. He was taken to Klagenfurt and interrogated for three days. He was abused, pushed around and beaten. But he kept repeating that the partisans had come and taken the pig by force and he had been unable to fight back. After three days, he was released but he was constantly observed and checked up on by the police. They came to the house regularly and searched for evidence of helping the partisans. I was always very scared and often hid under the bed. My parents were regularly interrogated and as a result they were terribly desperate and frightened.

Around the end of the war, a scattering of troops, among others Ustascha [1] and Weißgardisten [2] came to our house. They helped themselves to our food, using force if they weren't given anything voluntarily, all the while aiming at us with their guns. They found our potato supply and took everything. They also fought among themselves for our milk.

Due to his persecution and abuse by the National Socialists, Bartholomäus O. suffered terrible physical and psychological damage which severely restricts him, even today.

First publication of this article in: Renate S. Meissner on behalf of the National Fund (Ed.): Lives Remembered. Life Stories of Victims of National Socialism. Vienna, 2010, pages 208-210.