Gottfried A.

... we didn't want to have anything to do with this war

Gottfried A. was born in 1920 in a small Styrian village near Leoben. His father was harassed and persecuted as early as the era of Austrofascism due to his Social Democratic views, which affected the whole family. After the outbreak of the Second World War, Mr. A. was conscripted into the military and was assigned to the Mountain Infantry where he was trained to be a medic. During his training, he was often abused due to his family's political views. When he was finally sent to the Russian front in Finland and Norway, where he despaired at the acts of war, his plans to desert began to take shape. He then carried out this plan with a comrade. After a few failed attempts, the pair finally reached neutral Sweden. Once there, however, they had to sit out months in prison before, in 1943 – around one and a half years after their flight –, they were able to contact the future Austrian Federal Chancellor Bruno Kreisky and were able to move freely again.

I had seven siblings. We weren't badly off financially: we lived off Father's work and owned some arable land and small livestock. Our father was a Social Democrat, our mother was religious and we were brought up in the democratic spirit. I went to elementary school until the age of twelve and then spent two years at the further education school in Donawitz. The teachers were sadists and the classes were tough. The Catholic Church was very powerful and I was forced to go to confession from the age of eight to 14.

I had to begun to work when I was still young, watching the cattle and goats and helping out in the garden. There wasn't much time left for school work or hobbies. When I left school, I did various jobs; I was a hodman, a forestry worker etc. until I turned 18 and got a job as a turner in an ironworks in Donawitz. Unemployment was rife and we weren't in a position to think of further education.

My father was a miner and was sometimes laid up in bed after a mining accident. He wasn't afraid to speak the truth and to stand up for his political views. He was therefore constantly harassed by the conservatives around him. During the First World War, the army had hung him up by his feet and whipped him for protesting against the war. Under the Dollfuß regime in the 30s, the Social Democrats were persecuted. We had to sneak round the back of the store to buy our groceries. They threatened to fire my father from the mine if he didn't allow himself to be signed up to the fascist Home Guard. When he refused, he was provided with a uniform which then disappeared into the closet.

Civil war

On 12th February 1934, the Civil War broke out, in which the Home Guard were deployed against the Socialist forces. The Italian military – if rumors were to be believed – were at the Brenner Pass, ready and waiting to enter the country and assume power if it seemed necessary. My family also joined in and delivered supplies and ammunition to our units. The railway intersection Bruck/Mur was supposed to be captured, but the government troops were too powerful and after a week the fighting was over.

This was followed by persecution of the Social Democrats, with house searches and arrests. The Socialist leader Koloman Wallisch, with whom my father was acquainted, fled to the mountains where he was captured. On 19th February, after a [short] trial, he was hanged. My father was arrested and returned home after a month of torture.

On 25th July, the illegal Austrian Nazis staged a coup, which failed in Vienna but succeeded in other parts of the country. The gun battle went on for a week and during this time we remained passive. Afterwards, there were secret meetings in the woods between the Social Democrats and the Communists. Once, we found a Nazi weapons store, which we handed over to a Social Democrat representative. When the owners noticed the weapon theft, they came and vandalized the house and dug up the garden. They threatened to blow us up. Later, they burned down our barn, but that was where we had hidden the weapons.

The Austrian Nazis were always the worst and there were plenty of them in Leoben, even among our relatives. We were constantly spied on.

The German occupation

We all became German citizens over night. On 12th March 1938, the radio informed us that the German troops had crossed the Austrian border. It was immediately clear who followed the devil. Farmers threw their forks aside and swaggered around in their black and brown uniforms as a sign of their new worthiness. Everyone was urged to obtain swastika flags and hang them in their windows to greet the country's liberators. Many complied out of fear – I hung black paper flowers in the window (which I still had from a fair), but that was taken to be a mockery and a raging Nazi tore them down and hung a flag for us.

One day, while in Leoben, I was walking along with my hands in my pockets when the SA, the SS and the Austrian Legion [1] marched past. I received a sudden blow to the head. When I regained consciousness, an SS officer was leaning over me and informed me that I must salute when the flags go past and promised that next time I would be punished more severely. After this, I didn't like going into town.

My father was deemed a Jewish lackey. He secretly helped a few Jewish businessmen to flee across the Swiss border in a truck; they left eight hunting rifles behind, which we hid.

Three weeks after the Germans had marched in, our house was surrounded by about 50 Austrian Nazis and some ten of them stormed in with bayonets at the ready. We recognized them – they were old friends and neighbors who had often visited us and eaten with us at our table. Now they came with a different attitude: they pushed us up against the wall and shouted at us to hand over our weapons, flyers and typewriters, after which they searched high and low, smashing our furniture, cutting open mattresses and breaking open the floor. We were scared to death. When they didn't find anything, they took our father with them and abused him for a week.

In order to keep unreliable people under control, my older brothers – and others – were called up to the German labor or military service. This involuntary change of environment achieved the desired result on weaker-minded people: an acquaintance, who had previously described himself as a Fascist Communist returned from this retraining as a true Nazi. I had to cease work at the ironworks and was put to work on the lathe producing shells.

The neighbors bothered us constantly with their spying. Our father was threatened with prison and it seemed that he was only saved by the fact that he had managed to rescue injured colleagues from a gas explosion at the mine. When they wanted to decorate him for his deed, he answered: "Wear the medals yourselves, you snotty-nosed kids!" Then he was left in relative peace.

In November 1939, I was called up to the army for the first time but, upon the request of my employer, I was exempted until further notice with the argument that I already worked in the war industry. One day, a works policeman with whom I went to school stood behind me to check up on me and to provoke me. I told him to get lost. He said that he had to keep a special eye on the "young red ones". So I took a screwdriver and attacked him. He went to the office and made a phone call. Barely ten minutes later, four SS men were there and they took me to the headquarters. Once there, I had to listen to the lies that the works policeman had told about me. Then the SS gave me a very short hearing: "You are charged with refusal to work and exacting revenge against the police". Straight away, the two SS men took me under the arms and into their local. "Take off your shirt and lie on the bench!" Then I was tied up and they both whipped me until I bled. The pain caused me to faint. When I came to, the two SS men dragged me out of the room and put me on a chair in front of the Hauptsturmführer. He said, it wouldn't be the last time I was punished. Then I had to sign a paper saying that I injured my back in an industrial accident. Before I was allowed to go, they warned me to keep my mouth shut: "You know that your whole family is on the black list for Dachau!" When I arrived home, my mother asked me why I looked so pale. When she saw my bloodied shirt that was stuck to my back, she was shocked. I told my parents everything but we couldn't say anything. Until my conscription, every time I was off work sick, the works police appeared at my door with a thermometer. 39 degrees wasn't a fever – get in the car and off to work! Sometimes I considered suicide.

One day, when I was at the restaurant "Glück auf" in Seegraben, I greeted the owner as usual with a hello. The owner, Franz Lösch, now a legitimate Nazi, no longer approved of the customary greetings and barked at me that in his restaurant, he would only be greeted with "Heil Hitler". While I drank my beer, I studied the map hanging on the wall on which the German advance was marked with pins. Lösch approached me and taunted: "What do you understand of this map, boy?" He didn't realize that I was already looking for a way to flee the danger zone.

German military training

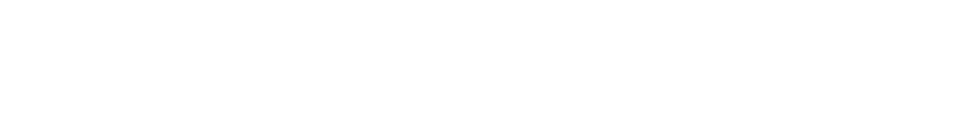

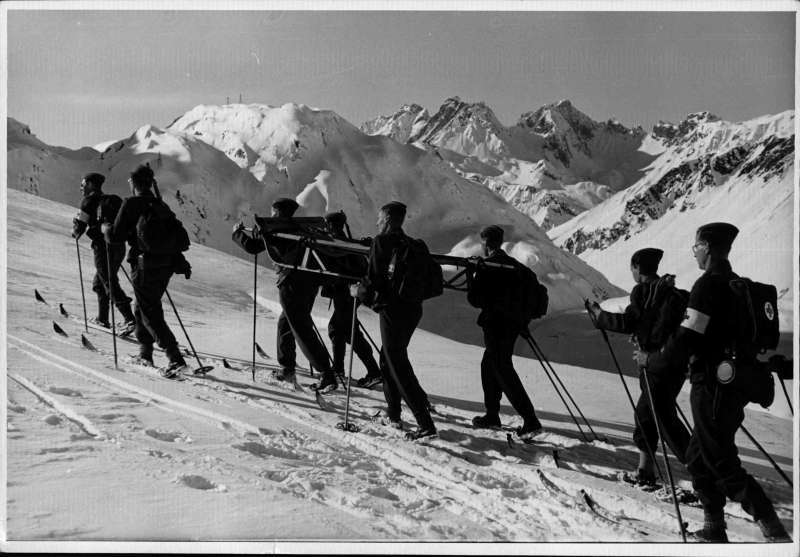

In January 1941, I received a renewed call-up from Berlin, which was to be complied with within 24 hours or I was to be court-martialed. Unfortunately, the master, who had twice helped me to avoid conscription said, "Mr. A., this time I can't help you". I presented myself at the nearest barracks in Leoben and from there, I was sent to Saalfelden in Salzburg. I was recruited into the Mountain Infantry and allocated to a mountain medic reserve unit in order to be trained to be a medic for the next eight months.

There were four companies of medics, primarily composed of doctors, medics, priests and seminarians. The sadistic commander drove four men to suicide, and older men suffered heart attacks when they were forced to run in the snow in full kit. Being chased up the hills belonged to the training – I was used to running in the mountains from home.

After two months of training, our company was assigned a Sergeant as our commander, who had been decorated with the Knight's Cross in the Polish campaign. I was shocked, because I knew him. He was a policeman from Judendorf near Leoben who our family knew well. Soon after, I was called into his office. Full of hostility and mocking, he said to me: "If I hear that you have been making political statements, you will be immediately demoted to the punishment battalion. Special leave is out of the question." Then he shouted, "About turn and out!"

One day, I had to scrub the corridor and the stairs. When I had reached the last step, he came and checked whether everything was clean with his finger. "Pig!", he shouted at me and took the bucket with the dirty water, went up a few steps and emptied it. "Continue!", he shouted. "What a pig!", I said to myself. He must have heard me. That same night at midnight, I was awakened. "Soldier A., fall in with your rucksack!"

I was completely shocked and stood there, barefoot and in my underwear, in the barracks yard in March. Then I had to pack bricks into my rucksack and run and lie down to the tune of his whistle. At the same time, I had to call, "I must not say 'pig' to an order!" For an hour he chased me across the yard like this, it was a big as a football field. Then he shouted, "Take the bricks out of your rucksack and get back to the barracks!" I collapsed in front of the door and crawled back on all fours until I fell, half-unconscious, into bed.

One day at the end of March, the whole company marched out to train. The commander was my "acquaintance" from Judendorf again. On the way back, we saw where the farmers had been spreading muck. He suddenly shouted: "Soldier A., step forward, lie down, crawl, roll and up, march, march, run!" Then he told me, he would make a good National Socialist out of me. I looked and stank like a pig. In the barracks, he ordered me to "line up in the yard in perfect dress in one hour, the Führer is speaking." I didn't have anything else to wear, so I stood in my wet uniform and froze.

After training, I was sent to a driving school in a monastery in Bregenz on the Bodensee, near the Swiss border. From there I wanted to flee across the border, but I changed my mind when I heard that four comrades had been caught attempting to flee – their death sentences were read out when we were lined up to serve as a warning to us. After completing driving school, I was ordered back to Saalfelden and had to help train recruits. One day, when we were outside and marching, I was put in charge of a group who were to be drilled […] up and down the mountains. But I was young and there were people much older than me in the group, so when we came to a little lake, I ordered communal bathing. It was June and the water was warm. But then the company commander appeared and ruined our fun. I was punished with two weeks arrest with only bread and water. Sympathetic comrades pushed sausage and bread to me through the bars.

War command

One morning in July, we had to line up in three ranks and we were told our fates. We were divided into two groups to be transported to Africa and to Russia. I had agreed with a friend that we would desert and join the English if we were sent to Africa. But I was ordered to Russia. We marched to the station and were transported to Germany in freight trains. We slept in Munich where I met a young girl, and with her, I tried to forget the seriousness of what was happening. The day after, we continued to Hamburg, where an air raid brought us back to bitter reality and gave us a glimpse of what awaited us at the end of our journey.

At the station in Copenhagen, Mountain Infantrymen thronged towards us from all directions: A loudspeaker called "Holidaymakers on their way to Germany by train, please take your seats…", but in reality of course, the train was northbound to Helsingör [2], where we had to pull down the blinds and were brought across to Sweden by ferry.

In Helsingborg [3], Swedish officers embarked and were invited to spend some pleasant time with their German counterparts. Around 200 soldiers – mostly Austrians – were squeezed into the overcrowded train and tried to dispel the boredom and uncertainty with singing and games of cards behind the lowered blinds.

In Kiruna we were able to disembark and stretch our legs. The thoughts of escape were at the front of my mind as we traveled through neutral land and I waited for an opportunity but the train was well guarded and the friendly relations between the German and Swedish officers did not bode well. We had also been warned: whoever tries to escape will be seized immediately and brought back.

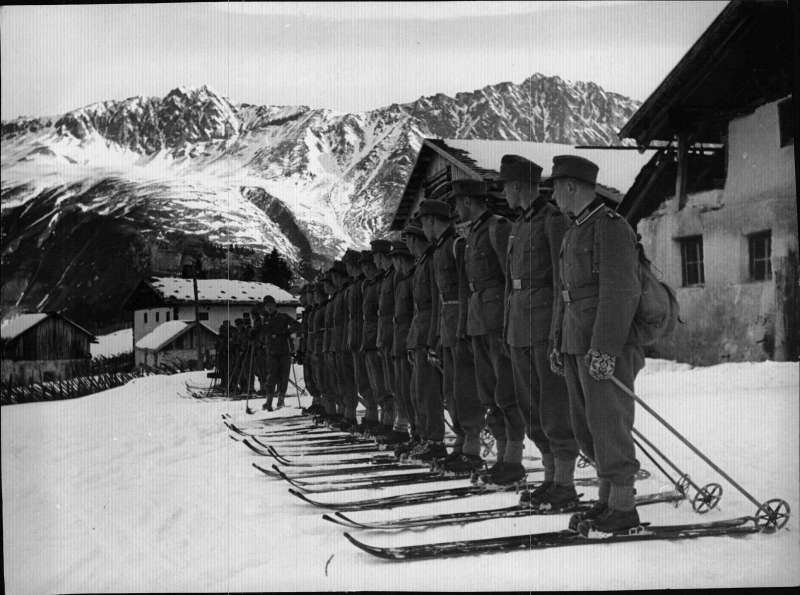

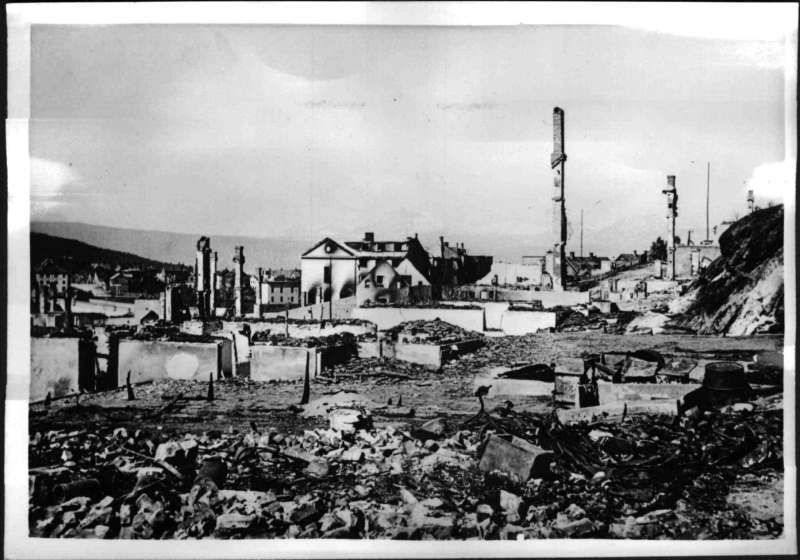

The train rolled endlessly on and in mid-July we arrived in Narvik [4], where we were put up in barracks while we waited to be transported further. There was mass destruction in Narvik, the port was blown to bits and full of sunken ships.

Freight ships docked with the coffins of fallen soldiers. I walked around the town and met lots of Norwegians. They could tell the difference between Germans and Austrians and knew the Edelweiß emblem, the symbol of the Mountain Infantry which we had on our sleeves. I gave them tobacco and got talking to fishermen, who had their boats anchored next to the war ships. A Norwegian teacher approached me at a cemetery – he wanted to help me escape to Sweden. But I was mistrustful and didn't know if it was a trick. I didn't know in which camp to place him.

To the front

On 25th July – after ten days rest – I was taken on board a transport ship with 2000 men and left Narvik that afternoon. We had heard that the ships were dangerous. When we came out of the fjord, we joined a convoy of ten similar war ships and were escorted by German ships. But danger was lurking on the open sea, and when, during the night, we were level with Tromsö, all hell broke loose. Ships in front of and behind us were torpedoed and blown up, ammunition exploded and the death cries of men and horses – who were standing tied up on the front deck – resounded through the night. Debris, hats and other loose objects [floated] in the water. When we docked in Hammerfest the next day, five transport ships were missing from the convoy and thousands of young men were gone forever, swallowed up by the sea on the coast of a foreign land. For them, the war was over before it had begun.

A few days later, we approached Kirkenes without further interlude. But there I received another shock. When we docked at the port, Russian prisoners of war – guarded by SS men – were in the middle of unloading a ship. It had been discovered that a bottle of wine was missing from the hold and ten Russians were taken and forced on to a truck which took them to the cemetery, where they were shot.

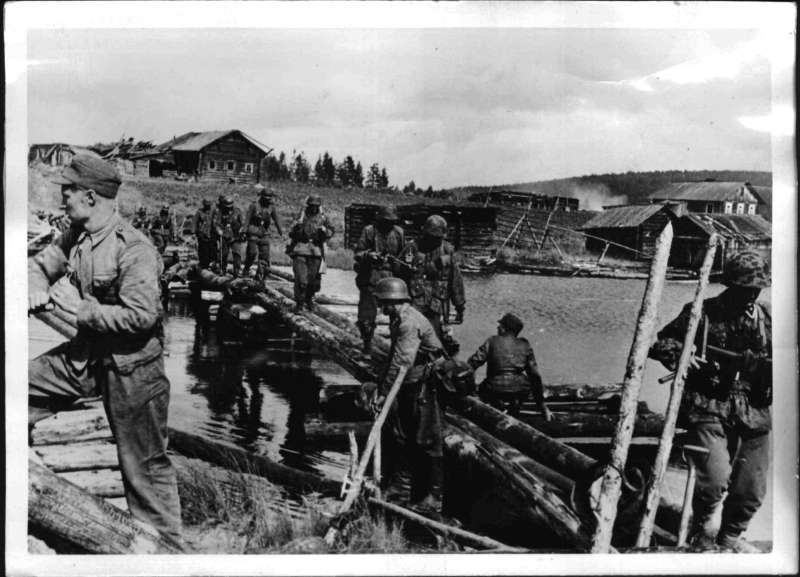

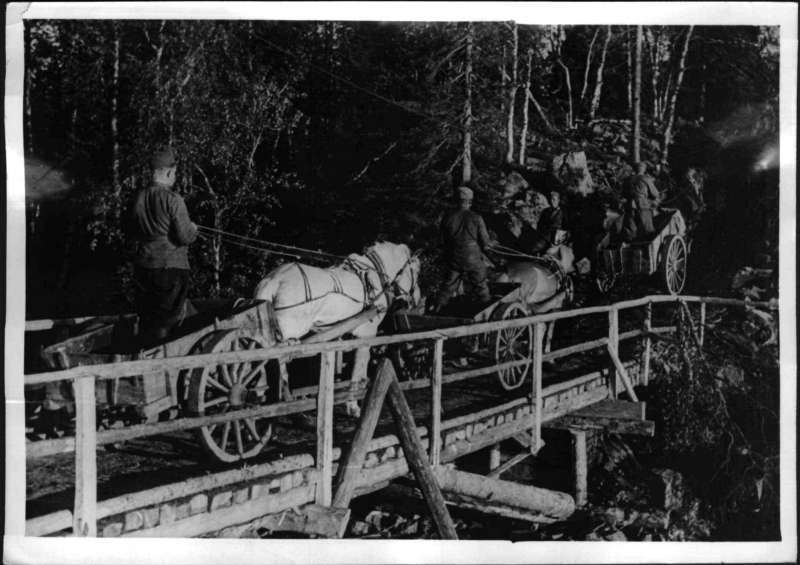

In Kirkenes, we were given our fighting gear and were transported to Petsamo [5] the next day. There were mass graves there, containing thousands of fallen soldiers. We traveled into Russia and over the first bridge that was guarded by the Waffen-SS and through the window we saw people in the German Labor Service who were doing heavy work on the street. After a further ten kilometers, we crossed the river Liza where we were divided into Mountain Infantry regiments and began the march to the front.

It was a hideous and shocking picture that greeted us on our march through the grim and artillery riddled Tundra landscape. Mutilated bodies lay at the side of the road, the smell was horrific and difficult to bear. They were mainly fallen Russians, as the Germans had already been removed, and they bore witness to the fact that there had been recent battles there. They were the terrible remains of Dietl's [6] first failed attack on Murmansk [7] on 21st June 1941.

We knew what we were heading towards, that we were to fill the holes in the German army and on this path which led to death, we had a preview of our own fate. I felt sick and couldn't eat for a week afterwards.

Under fire at Murmansk

It was late July and Dietl had already launched a second offensive against Murmansk. When we arrived at the front, we had to get into position immediately. This part of the front was defended by three Mountain Infantry regiments. Bombed-out nature – ridged marshland and stony birchwood forest – provided a desolate backdrop to the theater of war. Behind us was the muffled thudding of the German canons shooting at the Russian defense lines from where fire was returned only sporadically.

At last the order came to attack – suddenly the gates of hell opened and the Russian canons spat their destructive fire over us. I jumped for my life in the hail of grenades and didn't know how I was to help all of the wounded who lay in my path. An artillery attack beside me left me covered in earth and for a while I lost consciousness, but I got up and was uninjured. Surrounding me were fallen soldiers and medics who remained on the ground.

The German attack was broken and the losses could be calculated in thousands of dead and wounded. It was impossible to keep our positions during the Russian counter-attack and during the night the remaining forces withdrew. There followed one or two weeks of static warfare where we were thrown back and forward and involved in close combat. It was hot, and the Liza was full of bodies – the wind blew the awful stink of the fallen across no-man's-land.

We received back-up. A battalion of well trained elite soldiers from the Waffen-SS marched past with resolutely stamping boots, armed from head to toe and called out to us mockingly: "You country bumpkins, we'll take Murmansk in four days, we'll show you." With a signal from the whistle they led us into a renewed attack. But again hell broke out above us, the Russian artillery opened fire on us several kilometers wide. The earth shook and I thought the world was going to end. The elite battalion was mown down and among the desperate cries of the wounded you could also hear helpless whimpering for their mothers. An SS officer tried to force me with his pistol into the worst line of fire so that I would help them, but luckily my own commander came to my aid and saved me from a senseless death. The SS battalion was completely wiped out and the few survivors were taken prisoner by the Russians.

The losses were devastating. The Mountain Infantry regiments had shrunk from 1200 men to just 140 and it was no longer possible to maintain the original detailing. The other battalions had to be banded together. Of the 100 original medics, I was the only survivor who was uninjured. The food was poor and many got sick and died of stomach complaints. The nursing work was inhumanly difficult and I could hardly bear to bandage all of the cripples who had lost arms and legs. The medics were required to fight and to tend to the wounded with equal measures of unwavering courage. We also wanted to collect statistics of the dead and the wounded. Those who didn't manage were threatened with martial law and many disappeared in this way.

Sometimes, I came across wounded Russians in the battle field, who I also treated. Some showed me photos of their families – but the SS put a stop to this type of humanity and ordered me to shoot them instead. I never carried out this order. One time, a Russian soldier came running towards us and I was ordered by an Austrian Corporal to shoot him. When I refused, he grabbed the pistol to do it himself, but the magazine was empty and, to his visible annoyance, the weapon just clicked.

I was shocked and scared by my experiences of war, by the senseless suffering and death, and several times I thought of fleeing and handing myself over to the Russians. But I had seen some men try this and they were mowed down by machine gun fire.

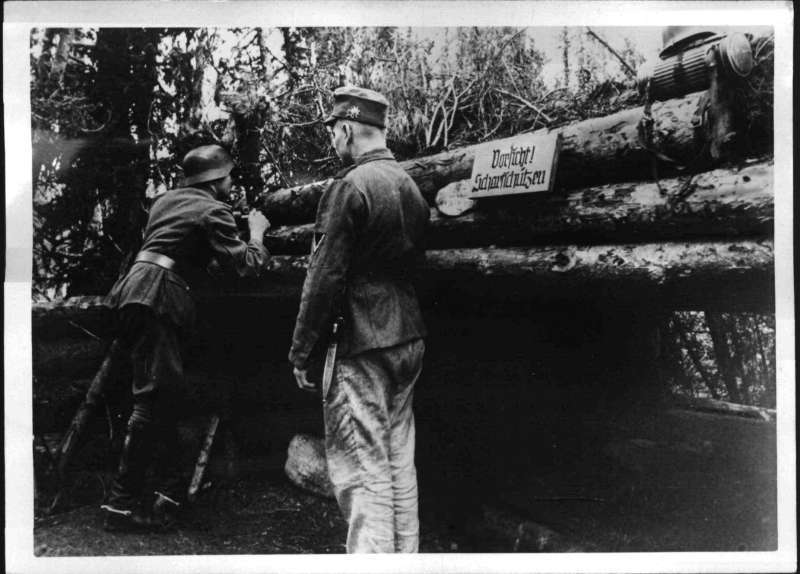

One day, I watched as a Mountain Infantryman from my battalion made a risky excursion into the dangerous terrain in front of the Russian snipers. Armed with a rifle and bayonet and with a blanket under his arm, he began his carefree ascent up a hill. I followed his foolhardy intention through my binoculars. He took stones up with him and, without particularly hurrying, built himself a small barricade. When he was finished, he lay himself down to rest behind his wall. But he had not rested for long before a Russian grenade exploded beside him and startled him. A moment later, another projectile hit his stone wall, shattering it. He screamed and I ran up to him and succeeded in dragging him to safety behind a rock. He had been wounded in the calf by the shell splinters and I applied the first bandage before carrying him back behind our lines.

His name was Franz S., 18 years old, from Vienna. I had heard talk of him before because he was different from the rest and considered to be a peculiar individual. He drank Russian vodka that he found and asked me straight up whether I was a Nazi and in favor of this war. When I denied this, he immediately suggested fleeing together. He said he knew a neutral country – he also mentioned that his father was a Social Democrat. I transferred my new found ally to the main medical station behind the front and didn't take his suggestion too seriously. After a week, he had regained his strength and came running towards me, brandishing a rucksack full of provisions and he had a field map of North Finland that he had stolen from a German officer. We left that very evening.

Escape through Finland

It was evening on 17th September 1941 when we left the front and, under cover of darkness, began our dangerous, uncertain tramp westward. It was cold, it had already begun to snow and we were ill-equipped for the approaching weather. In the rucksack we had supplies for a long journey as well as hand grenades and ammunition for our pistols in case someone should try to stop us. We tried to draw as little attention to ourselves as possible and lay for a while on a plateau in the dangerous vicinity. On the way down we came across an ambulance […] and we [decided] to [requisition the vehicle]. In an unobserved moment, [we carried out our plan].

I had in my pocket a referral to a military hospital in Petsamo which I had written myself and was issued to the injured Franz S. due to internal complications. He had already faked internal bleeding in the hospital camp by mixing cranberries into his stools which gave a doctor reason to sign him off sick for a few more days. We hoped that the Germans would understand that such injuries required an ambulance and with the patient behind me, I got into the stolen vehicle and drove to the Liza. The bridge was blocked by SS watchmen but the fake referral proved to be an adequate pass and the barrier lifted. With our hearts in throats, we rapidly left the dangerous territory without so much as looking back. After a time, we naturally ran out of gas but coincidence – which was our frequent companion on the way to freedom – saw to it that a German infantryman appeared on a motorbike with a sidecar. He took us with him and drove us to Petsamo. Up to here – but no further – we could use the fake pass and we now had to think of a new plan.

Next they seized the opportunity to travel with a convoy of German trucks. When they were asked the next day by a German officer to give a reason for their presence, they jumped from the moving vehicle and disappeared into the woods. Luckily, they were not followed and were able to continue their journey with another company. The Sergeant Major of this unit issued the escapees with train tickets to travel to Kemi, to where – as they told the officer – their headquarters had been moved. They continued on their way towards Tornea on the Swedish border and got off the train at Kalajoki where they slept with a Finish family by night and reconnoitered the area by day. The next evening, they braved their first step across the Swedish border, along a frozen river.

The escape in Sweden

Our escape was successful and we found ourselves in a free country. I felt safe for the first time during the war. We stopped a bus which was driving the sparsely traveled road alongside the river [8] and were able to board. The passengers stared in astonishment at our unfamiliar uniforms but it didn't alarm us, after all, we were in a free country. When the bus finally stopped and some plain clothed policemen boarded and took us with them. We were not in the least afraid. They took us to the police station in Kalix, where we spent the night under arrest.

We thought that the danger had passed and the war was over for us and that the worst that could happen would be to be detained for a while. But we were unwelcome guests and the police were confused about our appearance. At the police station in Lulea – where we were taken the next day for questioning – we were informed that without further formalities, we were to be taken back across the border.

It was dark when we arrived in Övertornea but we were able to faintly recognize the Finnish border guard on the other side of the Älv. Our pistols were returned to us and we were directed as to how to cross the ice unnoticed. The police's torches lit the way and kept a watchful eye on us as we commenced our lonely walk back. But before we had reached Älvstrand, we managed to diverge from the path and escape in the dark. After aimlessly wandering for a while, we stumbled upon some train tracks which we then followed, and during the night we arrived undetected in Haparanda.

Aware of the risks, we knocked at the first house that was lit. An astonished family invited us in and we told the daughter, who could speak a little German, our story. They were understanding of our circumstances and let us stay the night. The next day, they gave us civilian clothes and cut our uniforms into strips for rugs and burnt our identity papers. The son of the house contacted a Communist and we were advised to move south or to go to the Volkshaus in Gällivare. During the night, he procured some bicycles for us, on which we left Haparanda.

They didn´t want to accommodate us at the Volkshaus in Gällivare and in the hotel where we stayed the night, they called the police, who arrived to pick us up. Again we were brought back to Lulea and then back to the border. We understood that we would have to fight for our lives and on the way to Haraparanda – where we sat unguarded in the back of the car between two policemen – we opened the doors and threw ourselves out of the car, which was traveling at a fair speed. Of course, we were soon recaptured. The police threatened to shoot us if we tried to escape again and restrained us by tying us up with belts. In Kalix, we were handcuffed and were then driven at full speed to Övertornea. There, we were accompanied to the border and handed over to the Finnish police.

We were placed under German military guard, consisting of five or six officers and soldiers, and awaited our fate in a barrack. We heard them telephoning with Rovaniemi [9] and understood from the conversation that the Gestapo were going to come and pick us up. But when the Germans went to eat, leaving only one soldier to guard us, we seized our last chance. Franz asked to be able to answer the call of nature and when the soldier went out with him, I sneaked through the door and ran. Somehow, my comrade managed to free himself and I saw that he was running towards the river. I found my way northwards, heard that the Finnish police were chasing me with dogs and, several times, narrowly escaped capture. Under cover of darkness, I eventually managed to make my way down to the river and crossed at a frost-free pond-like area. Riding on a tree trunk, I reached the Swedish side.

Mr. A. was discovered by Swedish police. He fled through the woods and arrived at the same house where he had been taken in two days previously. There, he met up with his comrade. After three days, the pair traveled south on a freight train in the dark. When they were discovered by a railway worker, they again fled into the woods. They continued their journey south by night on stolen bicycles. By day, they slept in barns and nourished themselves with cranberries and stolen milk. Franz was stopped by police for having no light on his bike and taken to the police station. Mr. A. continued his journey alone and slept on a farm where he was awoken the next morning by two policemen and taken to the criminal investigation department in Stockholm.

I was interrogated for a week. The Commissar, Sandell, had sadistic tendencies and threatened me with all sorts of reprisals while pulling at my hair and my ears. I was interrogated in several languages but played dumb and pretended not to understand anything. Finally, however, a policeman arrived from Lulea and identified me. I also learned that Franz was here at the criminal investigation department too and was being interrogated in another room.

We were given a written deportation order and were put on a train going north, accompanied by two policemen. One of the policemen was a Nazi sympathizer and carried out his assignment with great relish. He threatened me with a "direct shot" if we tried to escape. As I celebrated my 21st birthday on the journey he gave me some cake and congratulated me on – what he hoped was – my last birthday. But in Haparanda the police were waiting and they informed us that a telegram had arrived from the [Swedish] Minister for Social Affairs Gustav Möller, according to which the deportation order was not to be enforced. It was my comrade who had written a letter to the Social Democrat minister and a helpful policeman by the name of Tuvesson from the criminal investigation department had delivered it to him by hand.

The Nazi sympathizer made a final effort by driving over to Finland and giving them our names and describing the course of events. But we were finally saved and were pleased to be able to stay in prison in Lulea.

The prison

The prison was a depressing, old-fashioned building which was heated in winter by means of a large, centrally-placed wood-fired oven. At first I found it warm and pleasant to spend our days there, much nicer than lying in Murmansk. But days, weeks and months passed without anything happening – no one seemed interested in us. It was called detention, but really we were in prison. We heard no news and I didn't understand why we were locked up like criminals – we hadn't done anything bad. On the contrary, we had distanced ourselves from evil. Later, I understood that as German deserters, we were considered a delicate matter which was best left alone. In the war year 1943, Swedish neutrality had sensitive nerves.

For nine months I sat alone in a cell of 2 x 3 meters, with no one to talk to in my mother tongue. I wasn't permitted to see Franz and at first, I didn't know where they had locked him up. The only interruption of this monotony was one hour of wandering around the prison yard, which was cold and miserable in the winter. Towards the end, the uncertainty and idleness had become unbearable and I thought that I was going to go mad. I broke out in cold sweats and threw myself against the door, trying to break out. I was plagued by nightmares about the war and being chased by the Gestapo. The food was poor and insufficient – slices of bread, sausage and porridge were on the menu, morning and evening and I felt myself becoming weaker. I sometimes dreamed of goulash and wiener schnitzel.

My mental and physical health deteriorated. A priest came every Sunday but he must have been an ambassador of the devil, because the only thing that he ever said to me, in broken German, was that I was supposed to be extradited. When I complained of pain in my diaphragm and was taken to the hospital barrack, I was received by the doctor who felt it his place to accuse me of shirking my duties in the German medics' service. He blathered something about the "blood of our German brothers" and told me I should be ashamed of myself for letting my countrymen die. That was his entire treatment – presumably he thought that that was the appropriate medicine.

I had to spend a month with a terrible toothache before being taken to hospital in Lulea for treatment. Unfortunately, they pulled out two healthy teeth and left the painful one in my mouth. I had a toothache for several months until the tooth finally rotted away. Later, I was no longer permitted to go to the dentist, which I perceived as a form of torture – there are many ways to torture a prisoner, including by not helping him.

I encountered Fascism in many different guises – in the work clothes of a farmer, the uniform of a policeman, the black robes of a priest and in the white overall of a doctor. In prison, it also appeared in the uniform of the commander. He was a man of extreme good humor, as long as the Germans were doing well. But among the guards there were also decent people with sober political views. […]

One day, I made contact with Franz, who was in the cell below mine, through the so called bush telegraph and using a piece of string we were able to pass notes to each other through the bars of our windows. Together, we composed a letter of complaint to Gustav Möller, to which we never received a reply – the letter probably got no further than the guards. Sadly, our secret contact was discovered with the consequence that Franz was moved to another cell out of the reach of my string.

One day, I heard some people cursing loudly on the stairs and I recognized Franz's voice – then I heard a crash and when I asked a guard what had happened, he told me that my comrade had fallen down the stairs and hit his head. Later, Franz told me himself that a guard had pushed him down the stairs and that was the reason why he has suffered epileptic fits since then.

We succeeded in re-establishing contact over the bush telegraph and in early May, I received the news from Franz that another Austrian had arrived in the prison. They were obviously of the opinion that he wasn't a dangerous influence, because he was put in the cell with Franz. I saw him a few days later when he was marching up and down the prison yard in his fine leather boots. His name was Fürst and he was a Mountain Infantryman from Salzburg. When I had gotten to know him, he bragged about his father's Nazi views and said that he was proud to be a soldier in the German army. However, due to an unfortunate set of circumstances, he managed to miss a call-up and for fear of being punished he had wandered around northern Norway until he accidentally crossed the Swedish border. He regretted this mistake and had requested his extradition – but they held him against his will.

After months of patient filing with a knife blade, I had nearly succeeded in lifting the window bars when I finally met up with Franz and the new arrival in the yard. They had already come up with an escape plan and we decided to carry it out immediately. In an unwatched moment, we pulled forward a wooden cart and leaned it like a ladder against the wall, a three meter high slab wall with barbed wire, which we climbed up and jumped over. Unfortunately, when he landed on the other side, Franz broke his femur and lay helplessly on the floor as we ran away and tried to escape the city.

During their escape, both men broke into holiday homes in order to take food and clothes. However, they were caught and returned to prison by the police. On 13th August 1942, they were sentenced to three months imprisonment by the court in Nederlulea. They were offered extradition as an alternative. After a total of 16 months in prison, in April 1943, Gottfried A. and Franz S. were finally transferred to an internment camp.

Internment camp

We were taken to a make-shift interment camp in Kalmar-Schloss which was inhabited by refugees of various nationalities. I recovered and began to foster hope for the future. Franz wrote to Bruno Kreisky in Stockholm, who came and visited us and promised to help. Four months later, we were sent to the Langmora internment camp in Dalarna.

During the three-day holiday trip to Sweden, where we were visiting Kreisky, we came into contact with a family called Eriksson who were Social Democrats and had a certain amount of political influence. They helped us to receive permission, after four months in Langmora, to live in Stockholm with this family as our guarantors. We were given a Swedish foreigners' pass but were forbidden from leaving the city for the duration of the war. The extradition order was not lifted until 1946.

Why my friend and I deserted

I was active in an illegal youth group of the "Revolutionary Socialists" for a democratic Austria as early as 1934. The father of my friend was a member of the Republican Defense League and had taken part in the February Revolt. He was in prison for several years. My father had been imprisoned for the same reason in Leoben for six months and was subjected to physical torture. They didn't care about my mother, who was left on her own with eight children. Only acquaintances and those close to us came to our aid.

To travel from Murmansk to Sweden via Finland was a long way and a difficult decision. But we risked it because we didn't want to have anything to do with this war and wanted a free Austria. In Sweden I was active in the "Austrian Association". Its chairman was Bruno Kreisky.

First publication of this article in: Renate S. Meissner on behalf of the National Fund (Ed.): Lives Remembered. Life Stories of Victims of National Socialism. Vienna, 2010, pages 174-191.