Hemma V.

Suddenly there was only German

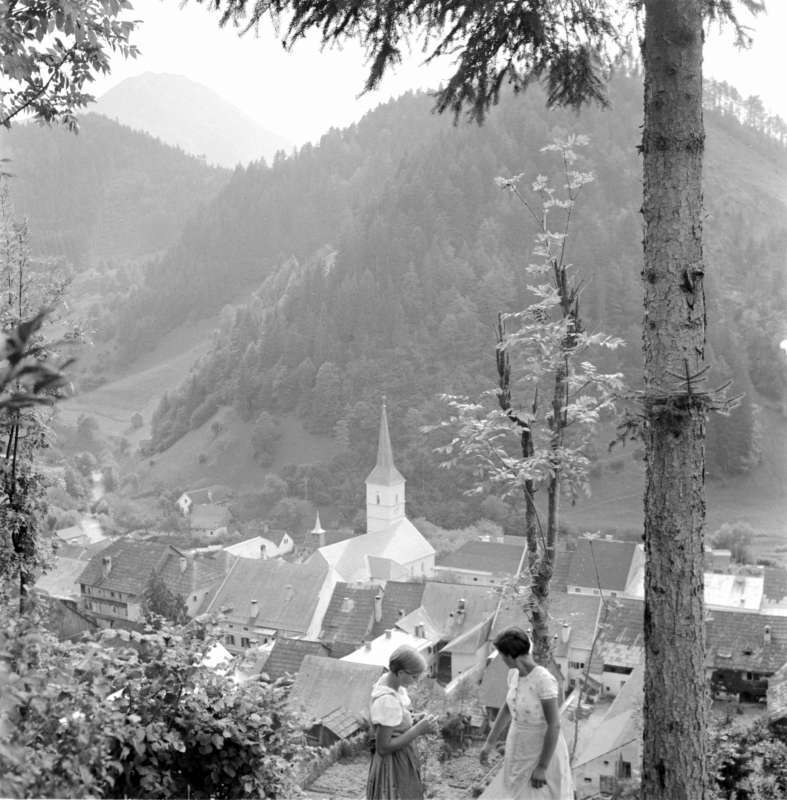

Hemma V. was born into a Slovenian family in Remschenig/Remšenik in Carinthia in 1935. Her extended family lived on a small, leased farm.

Hemma V.'s father was conscripted into the German Armed Forces. Before he could carry out his decision to join the partisans on his next visit home from the front, he was killed in action. Mrs. V.'s mother was active in the resistance movement and supported the partisans. Even as a small child, Hemma V. had to suffer awful humiliation and witness many terrible things. At school she was mentally and physically abused, the family was spied on and threatened with deportation. These experiences have taken their toll on Hemma V. and even today she still suffers from panic attacks, nightmares and depression.

I was born in Remschenig. My parents had rented a small farm and we had two cows and two pigs. My grandpa, grandma, a brother and a sister also lived with us. We only spoke Slovenian at home. When the war broke out, my father was conscripted into the German Army. We only saw him one more time and then he was killed in action.

In 1942, I started elementary school in Eisenkappel. Suddenly, there was only German. The teacher wouldn't hear a word of Slovenian, but I couldn't speak any German at all. It was awful. I had to kneel in the corner for hours. As I had big scabs on my legs, a pool of blood always formed around my knees. It hurt terribly. But if I cried, I was beaten with a stick. How often I wet my pants! Sometimes because I didn't know how to ask to go to the bathroom in German and sometimes because I was scared. I was terrified of the teacher and didn't want to go to school any more. I often waited in the woods until the morning was over. Of course, the result of this was that I had to re-sit the class. There were also lots of air raid warnings. Often, these saved me from being punished, because we all had to go down to the cellar.

In 1943, the resistance against Hitler slowly began to pick up pace. In Remschenig we heard talk of it, very secretively, but we hardly ever saw a partisan. One day, three or four "partisans" came to our house. My mother warmly welcomed them and gave them milk, bread and porridge to eat. They asked lots of questions and mother gave them long answers. They also asked why my father didn't change fronts. My mother told then that as soon as my father was on leave from the front, he would join them. The "partisans" said goodbye and nobody in the house suspected a thing. When, a little later, my sister wanted to go to the barn, she saw the police behind the building. She ran back into the house and it was only then that it dawned on my mother that we had been visited not by partisans but by Germans in disguise. Grandma and Grandpa began to wail and we were all absolutely terrified. Although the Germans then retreated, my mother was still deciding what to do. In panic, we grabbed our blankets and went into the woods. We spent the first night there sleeping in the open air. My mother consulted with my grandparents and the next day, my grandparents returned to the house with us children. My mother, however, joined the partisans, where she remained until the end of the war.

Now the Germans started coming more often, asking after my mother. My grandparents told them that the partisans had taken her by force. They also wanted to question me and my sister. They put chocolate on the table and asked us whether we had seen the partisans and our mother. Although we really wanted the chocolate, we didn't say a word – or take the chocolate. They came more and more often. They regularly stayed overnight. They carried straw into the kitchen and slept there. In the yard, the watchmen [stood] with their rifles at the ready. They waited for my mother and the partisans in vain. The partisans only came by when we had hung a white sheet on the clothes line, because that meant that the coast was clear – as we had arranged with the partisans. But we were always scared when unknown partisans came because we never knew if they were just Germans in disguise. The fear remained until the end of the war.

The partisans had a bunker near our house and there were always three couriers. They often came to our house and Grandma gave them food. Shortly before the end of the war, one of them was shot and he died agonizingly 14 days later. My sister [brought] him tea and food, but he couldn't eat because he had been shot in the stomach. One time, the partisans brought a man with a broken leg. They spent the night at ours asleep on the threshing floor and in the morning they took him to a little shed about a half an hour's walk away. It was deepest winter. My sister had to bring him food every day, for fourteen days on end. As this was very dangerous, and in order not to raise suspicion, I sometimes had to accompany her. This was very tiring, as there was a lot of snow on the path.

When around 15 families were evacuated from Remschenig, the Germans came to us as well. As my grandmother was very sick and bed-ridden, they only took my aged 80-year-old grandfather with them. The next day they released him again – it was a miracle. To this day, we don't know why they let him go.

The worst time was when, one day, the Germans brought three of our neighbors to us. With their hands bound together, they had to spend the night on our threshing floor before being deported to Eisenkappel the next day. We were not allowed to help them. When my grandmother wanted to give them something to eat, a German said to her: "Bandits don't need food!" It was terrible, we were all crying. My grandmother was often afraid that we would also be deported like that one day.

I'll never forget the time when the Germans shot a partisan on the bank of the stream near our house. I went over the bridge and saw a blond man lying in the water. He lay there on his back, covered in blood. I can still see this image clearly, how could I ever forget it? Of course, I was also terrified.

When, in May, the war was officially over, hordes of Ustascha [1] continued to come across the border. We were very scared of them, as they often shot wildly around the area. My uncle (my mother's brother), who at first fought on the German front, then joined the partisans and then, near the end of the war, was taken captive by the Germans, survived the war. And then he was shot by the Ustascha at home on his mountain farm. Oh how we cried.

First publication of this article in: Renate S. Meissner on behalf of the National Fund (Ed.): Lives Remembered. Life Stories of Victims of National Socialism. Vienna, 2010, pages 217-219.

[1] A Croatian Fascist movement in collaboration with the German Reich.