Katja Sturm-Schnabl

From the recollections of a child about the National Socialist era

Born in 1936, I grew up with my sister Veronika and my brothers Andrej and Franci in a Slovenian extended family on a farm near Klagenfurt.

In addition to my parents, grandparents and two aunts, six or eight laborers also lived on our farm and at harvest time there were also day laborers. These adults all treated us children as people in our own right, they involved us in what was happening, took us with them into the fields and the stables and answered our questions smilingly yet seriously. I never heard a bad word spoken and was never even threatened with as much as a spanking. Exciting things happened, like the birth of a foal or calf, a litter of piglets, young dogs or cats, lambs, chicks, meadows full of colorful flowers, a stream with fish, crabs and shells, a forest where you could pick berries and mushrooms. Friends or relatives often came to visit. How exciting it was when they sat at a set table in the reception room on the first floor and conversed with my grandparents and parents. Then we could sit quietly in the corner and hear about so many things about the world beyond our own. During one such visit, it dawned on me for the first time that our world, in which my mother and father were the supreme authorities, was endangered. The visitor, a friend of the family, had brought a map of Europe with him which he hung on the wall in order to explain to my grandfather and the others a situation in which the "Nemci" (the Germans) were doing terrifying and threatening things which could also happen to us.

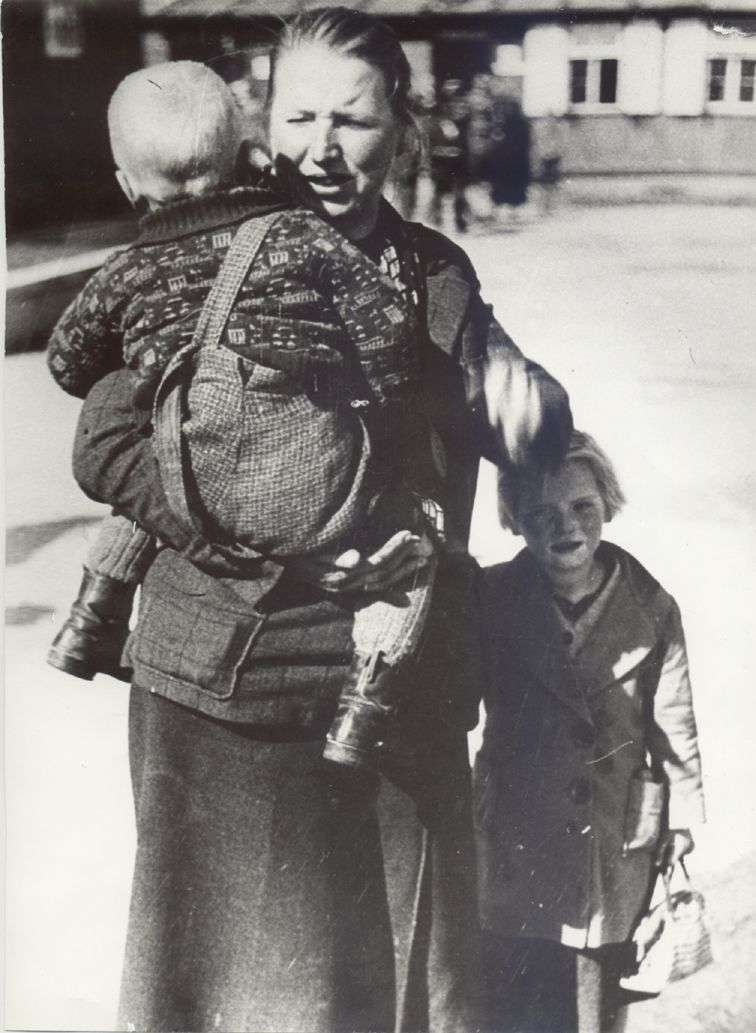

And one day, a Thursday, when my mother and father were in the town, they came. In uniforms, in boots, weapons fixed, with pistols and military caps on their heads. They stormed into the house, shouted incom- prehensible things in abrupt sentences (when I was a child I didn't understand German) and there was immediately indescribable chaos in the house. My aunts cried, the maids cried too – there was great confusion, the "Nemci" shouted and I was gripped by a total panic because my parents weren't there. I hid until they returned home. Then, stony-faced, my mother began to dress us four children (my youngest brother Franci was two-and-a-half years old, my sister Veronika seven, my brother Andrej five and I was six). A few sacks were gathered and some clothing and such was thrown into them. Then, we – my parents, my aunts and us children (my grandfather was no longer alive and my grandmother was visiting an aunt, her third daughter) – had to leave house and home [1]. "Nemci" to the left and right and us in the middle, that is how we were taken away, we had to walk through the village and then another two kilometers by foot until we reached the road. The red bus, which had been waiting on the road, brought us to a place with many long, low-rise wooden barracks within a barbed wire fence. [2] In one such barracks, we met our maternal grandmother, an ancient, fragile little woman (she was 83 at the time), she was lying in this barracks on straw (like we had strewn for the cows at home) and next to her, my uncle's youngest child (a six-week-old baby, Maks). When she saw my mother, she kept repeating "Nemci nas nekam vlečejo." ("The Germans are taking us somewhere.") Yes, and around the barracks were these "Nemci", in uniforms with caps on their heads, with boots, weapons, pistols and unsmiling faces, looking so angry, like I had always imagined the villains in the fairytales to look. One of them took a photo of my mother with us and when he was gone, she said scornfully, "And in my moment of deepest humiliation, he has the impudence to photograph me as well".

After three days, we and the others living in these straw-scattered "stables", including so many friends and former visitors of my parents and so many uncles, aunts, cousins, were moved on further. We reached some wagons which we were herded into, the doors were closed and we stood in the pitch black. In this darkness we continued to roll on our way, days, nights – it seemed like forever. Every now and then, someone tried to light a match, others cried hysterically because they feared a fire, in between there were attempts to calm down. My mother had us all pressed to her like a hen with her chicks, which made me feel even more claustrophobic.

After this seemingly endless darkness, fear, hysteria, and helplessness in the rolling train in locked cattle wagons, we came to a halt, the doors were thrown open and we staggered out into the glaring light. The train station was called Glasow (near Stettin/Gdansk). Again, our pathetic rabble was herded on further. We marched across a dusty street, my mother held us close to her, people were standing at the sides of the road staring at us.

Then the arrival at a huge building – the camp. [3] Staff who bellowed our room allocations – men, women – at us. Then everyone had to strip and we were herded into a shower room in the cellar. I shall never forget my aunt's horrified, terrified face. She later told me that she had been convinced they were showers intended to kill us.

Recollections of the food. We children were separated from our parents and fed in a "children's dining hall". The camp commandant, with gleaming waxed boots into which he had thrust his whip, walked up and down with a large sheepdog. I didn't want to and couldn't eat this compulsory food. Every time the camp commandant passed my table with his dog, the waxed shoes and whip, he bellowed louder and more angrily something I couldn't understand but which I of course gathered must mean "eat up!". And although I was already vividly imagining that he would have his dog tear me apart, I couldn't and didn't want to eat. My sister Veronika tried to persuade me, but I didn't want to and when the atmosphere had become heavy with fear and the camp commandant's bellows increasingly loud, my sister seized the moment when the commandant had moved towards the other end of the table and gobbled down my portion – I was convinced that she had saved me from a terrible death.

The adults were assigned work. My mother had to go and housekeep for a woman. Her whole cottage was no bigger than our dining room at home. But the woman could now afford to call on a domestic help from the neighboring camp. Proudly, she told my mother how her husband was a soldier in Yugoslavia and showed her the "treasures" he sent her in weekly packages: Curtains, bedding, textiles etc., all things that she couldn't have afforded before the war. My mother said to us "And she's not even ashamed even though she must know that I've understood that they are stolen goods". And then I knew that the "Nemci" had driven us out of our home because they wanted to steal our house, our farm, all of the animals and everything we had in our rambling house; they weren't at all ashamed and proudly showed off what they had stolen.

After three months, we were taken from this (temporary) camp to another in Eichstätt in Middle Franconia [4] where we remained until the liberation.

The camp commandant, an SS-Obersturmbannführer, also had waxed boots and a sheepdog. He held so-called roll calls, i.e. all camp inmates had to collect at a certain place and he stood on a platform and bellowed, bellowed, bellowed and everyone had to listen to his bellowing. Even though I didn't understand German, the sentence "Ich werde euch alle vergasen lassen" ("I will have you all gassed") remained in my mind. Once, a Red Cross nurse dragged us children for two hours to glean. The youngest were four, the oldest twelve years old. I shall never forget the heat, the strain, the tears of the youngest, the harsh shrill voice and unsympathetic face of "Sister Agnes".

It was not long before my father was sent from this camp to Karlsruhe to carry out forced labor (armaments industry). My mother initially worked as a housekeeper for a lady whose husband obviously held a high position. Then she was sent to help the farmers with the harvest. Finally, she worked in a shoe factory. She always got up at 3 am to secretly make soup for us children in the laundry. I don't know how she managed it.

I kept on trying to eavesdrop on the adults' conversations and as a result I knew of the resistance campaign under General Tito. He became my hero, I believed that he was personally taking care of my fate. For this reason, I found it all the more bitter when someone died in the camp, for he would not live to see freedom.

Then Death visited us too. An epidemic broke out among the children, the camp doctor apparently didn't find it so terrible that so may children were dying – I cried bitterly over the death of my young friend Zvonko. Then my sister Veronika. It was not until many years later, after my mother's death, that I met an eyewitness who told me how my mother had carried my eight-year-old sister to the camp doctor. He had given her an injection and she died instantly in my mother's arms. My mother had never told us. Above all, she wanted to at least let my father, who had his whole life never got over the death of this child, believe that his daughter had died a natural death.

As the community authorities of the town feared that the epidemic would spread to the town, the rest of the sick children were taken to the municipal hospital. Through this, we – my brother, the other camp children and I – were able to survive. One day, our mother visited us there, after weeks the nurse told us for the first time that mother was coming. I wanted to joyfully run towards her and when I saw her, she was so different. Although she should have been pleased to see us there was no smile on her face, no joy in her eyes. For a long, long time, she didn't speak a word, no sound came from her lips until finally, in a voice which seemed alien and was barely comprehensible, she said "Veri je umrla" ("Vreni is dead"). In this moment, the world around me froze. I didn't dare cry. I couldn't do anything to counter the death of my sister, the pain of my mother. I still can't. My bewilderment at what I had to live through for three and a half years continues to stay with me every day.

Katja Sturm Schnabl' s life story first appeared in its full length in the feminist magazine AUF. Eine Frauenzeitschrift (issue no. 66, December 1989).

[1] In April 1942, there was a large-scale operation to "resettle" around 1,000 Carinthian Slovenes, who were deported to "Altreich", where the majority had to live in camps until the end of the war.

[2] There was a so-called collection point in Ebenthal near Klagenfurt from which the deported families were transported onwards.

[3] This "resettlement camp" was situated in Rehnitz (today Renice in Poland).

[4] There was also a "resettlement camp" for Carinthian Slovenes situated in Eichstätt in present-day Upper Bavaria.