Koloman Baranyai

Today they are taking the Roma away …

Koloman Baranyai was born on 31st March 1941 in Katzelsdorf/Niederösterreich. His family belonged to the Roma community.

Thanks to the good relationship his father enjoyed with the non-Roma people, for whom he played music and did odd jobs, the family was warned about a raid and was able to flee from the Nazis in time. Mr. Baranyai survived with his family by hiding in the forests of Austria, Hungary and the former Czechoslovakia. His uncle, aunt, their children and his grandmother were murdered in the camps.

The following excerpt is taken from an interview (conducted in Romany) from the contemporary witness documentation "Mri Historija. Life stories of Burgenland Roma" by the association "Roma Service".

First we fled to Hungary. We stayed there for a long time. We lived in the forest. My father always went into the village in the evening. There were businessmen who knew him. They opened the back door for him and let him in. Then my father quickly took the things he had bought and in this way, we had something to eat. And then the Hungarians said to him "Julo, watch out! Today they are taking the Roma away. Make sure you escape with your family!" And so we fled to Czechoslovakia. We also lived there for a long time, again in the forest. We were lucky that they didn't catch us, because lots of people fled from there, but the SS men imprisoned the majority and deported them. […]

We always had supplies. My father always made sure that we also had something to eat, even if there was a great lack of food. He always made sure of this and if there were sometimes no food, he caught rabbits in the forest. If he caught sight of a deer, he killed it and we had that to eat. […]

The Gadsche (non-Roma) all knew that we were Roma. They didn't betray us, because they liked my father a lot. My father never said, "No, I can't do it, I can't help you". My father was always willing to help. That is why they always gave him something to eat. They wanted to give him money too, but he said he didn't need money, he preferred groceries. […]

My grandfather, my mother's father, died of worry. […] My grandmother – I don't know which camp she was sent to – was murdered in this camp. We only found out after the war, that she was murdered in a camp. My Uncle Albert, my mother's brother, was sent to Auschwitz. He was murdered there a week or two later with his family, his wife and two sons. […]

The Roma who came back and who had all lived in Hungary had a wretched existence. Their houses were all gone. "Confiscated" by the SS or destroyed by bombs – everything was difficult. Not a single one of us was doing well! How should I say it? No one can really describe it properly. Everyone was sick, very sick. They either had something with their hearts or with their lungs. One after the other, most of them died.

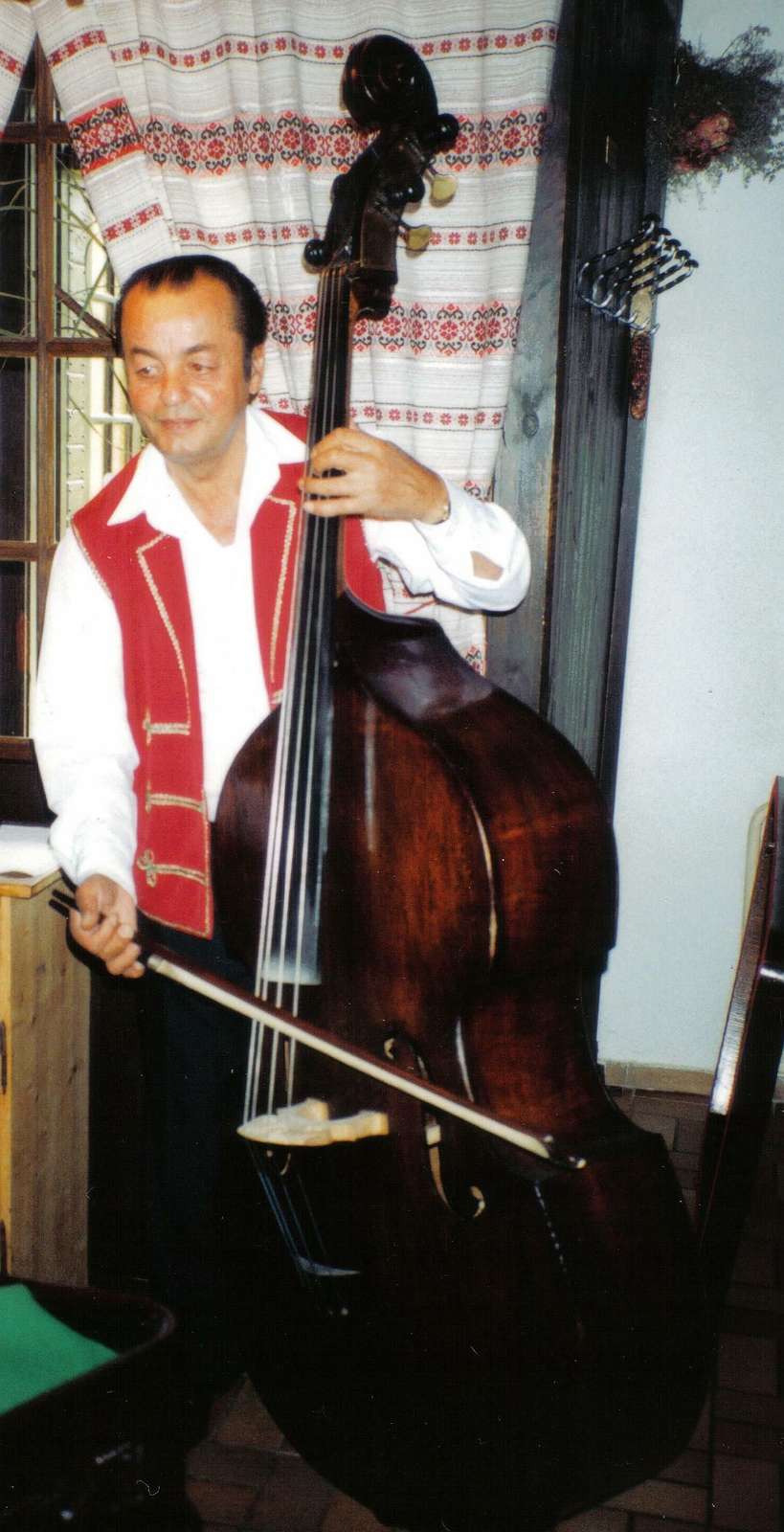

After the war, the family settled first in Heiligenkreuz and then in Baden, near Vienna. When Koloman Baranyai was eight years old, his parents separated. His mother felt forced to leave her two sons with a family of farmers where they remained until the age of 14. They had to help on the farm and so could only go to school very infrequently. At 14, Mr. Baranyai returned to his mother and began to work for a construction company. But Koloman Baranyai, who had already learned to play the violin as a child, saw music as his true calling.

And he [my father] said to me, "Kalman, what do you want to learn?" He didn't dictate what I had to learn, but definitely a musical instrument. And I had to become a musician. But he did say to me, that I can choose which instrument, he didn't mind. So I began to learn violin, I could already play a bit. We children used to act like clowns, and one day I got my hand caught in a cutting machine and cut off my finger and then I couldn't learn any more. Then I started to learn the viola, but I also found this difficult because of my finger, so I stopped that too. So in the end the double bass became my main instrument. […]

Koloman Baranyai's identity as a Roma, his close relationship with his mother tongue and his identity as a musician are still inextricably interwoven.

First publication of this article in: Renate S. Meissner on behalf of the National Fund (Ed.): Lives Remembered. Life Stories of Victims of National Socialism. Vienna, 2010, pages 257-261.